INDIA

The following report, submitted by Dr. Catherine Berry Stidsen, (seehafer@csus.edu), reveals the perseverance, courage and imagination of some of the pioneers who are providing quality education to people around the world.

A Report to the Canadian National Literacy Secretariat on The Nagpur Learning Centre Maharashtra, India

This report explains the genesis, construction, and present operation of the Nagpur Learning Centre, Maharashtra, India. This resource centre, operating in a developing nation, is playing a vital role in the advancement of literacy and numeracy, at several levels. The education of women is of special concern. The report concludes with suggestions for how the literacy community in Canada might facilitate the development of and service within such centres.

The Genesis of the Nagpur Learning Centre

In 1981, a few months before his death, my husband, Bent Stidsen, Ph.D., a member of the Faculty of Business of McMaster University, professor of marketing and communication relations, expressed to me his extreme concern with the numbers of foreign students, especially Indians, who were coming to Canada to study and then remaining here. He felt that Canada was guilty of a brain drain in terms of India in particular, and since all the signs in international marketing were that that country was moving toward a freer market economy, it was essential that students with marketing and entrepreneurial skills return to India to help with that transition. He was convinced that a far better approach for Canadians to be taking would be that they provide resources to developing nations in their own countries. Those resources need to be both materials and persons. For two years prior to his death, Dr. Stidsen was instrumental in establishing what has now become Canadian Executive Services Overseas (CESO). This organization sends Canadians to work in developing nations at the request of host countries for short periods of time. He also served on four other federal and provincial committees involved with what has now come to be called sustainable development. All of his efforts were involved in helping people to help themselves. At the time of his premature death in 1981, his library contained economics, marketing, and communication classics, along with several philosophy of marketing projects, including his own three books and some fifty publications and monographs. With his colleague, Professor Jean Drolet, of Bishop's University, Sherbrooke, Quebec, it was decided to place copies of the books and monographs in Sherbrooke where he had taught a Philosophy of Marketing Action course successfully for ten years as a sessional lecturer. Professor Drolet was his associate for these courses. However, since the books involved were available at the University of Sherbrooke and Bishop's University, it was decided to leave his personal library intact for the time being.

I expressed my husband's concern about Indian students to Professor Drolet and asked him to keep this in mind in terms of the eventual disposition of the library. My husband's Indian colleagues at McMaster agreed with the need but had no suggestions about where the library might go. For the next five years, while I completed two manuscripts of my husband's, and arranged for their publication, viz., "Marketing: A Canadian Perspective", and "Communication Relations", I began to research aid agencies in India which might be able to use the library and with which I would deposit the books and monographs as well. While some were interested, in particular the Shastri Indo-Canadian Foundation, they had no way to transport the library to India, and offered no suggestions about how that might happen. Air India had once shipped such professional libraries to India but had ceased to do that the year of my husband's death. I wondered personally if the library and publications ought to go to Bombay or New Delhi where most of the aid agencies had offices or to another location where living costs were far less than in major Indian cities and where financially disadvantaged persons could have access to the materials.

In 1986, an Indian colleague of mine, Dr. Leobard D'Souza of

Nagpur, India, visited North America for the first time in almost two decades.

I had written to him at the time of my husband's death of his concern about

Indian students and my desire to use his library in some intelligent way in

that country if at all possible. Dr. D'Souza spent five days of that visit with

me and marvelled at the extent of my husband's library and my own during that

visit. In his own city of Nagpur, he had just completed a major needs assessment

of educational and social service institutes and chief among suggestions coming

from persons in these agencies was a need for a library. As we spoke of the

Nagpur need it became clear to me that what people were actually asking for

was a media resource centre.

It was decided that Dr. D'Souza would continue his local needs assessment, I

would investigate in depth the movement in Canada toward the extension of services

now being offered in libraries, and would continue to seek a source to transport

the library to India.

In the spring of 1987 it was possible for Dr. D'Souza to return to Canada for ten days. During that time we visited adult basic education centres in the Hamilton area and also English as a Second Language Centres. We toured school, university, college, and public libraries as well. I had not as yet been able to find an organization which would ship the materials to India. A major disappointment occurred when at the recommendation of the Ontario English Catholic Teachers' Association, I approached CODE (Canadian Overseas Development Education), to find that its version of "overseas" was, and possibly still is, Africa and the West Indies. Personnel at CODE advised me that "India does not have the infrastructure we require" to ship materials there. During Dr. D'Souza's 1987 visit it was agreed that I should visit Nagpur personally from December of 1987 through January of 1988. (I was on leave of absence from teaching completing course work for my doctorate). I did so and in a brief visit with the then director of the Shastri Indo-Canadian Foundation in New Delhi, I was advised that the academic affairs officer of External Affairs might be amenable to a shipment of books on a one-time basis. I then toured the areas served by the Nagpur Roman Catholic Diocesan Corporation, in Mahrashtra and Madya Pradesh. Dr. D'Souza is the educationist who directs those services and is the archbishop of that corporation.

In my own needs survey, discussion with diocesan personnel, and extensive discussions with Dr. D'Souza, it became clear that we needed immediately : a) tutorial programs in English, mathematics, and science for financially disadvantaged students preparing to write matriculation examinations which would admit them to colleges and universities; b) literacy courses in English, Hindi, and Marathi at the survival, proficiency, and advanced levels; c) professional library resources for persons reading for examinations at the bachelors' and masters' levels. Briefly, the rationale for these programs is as follows. In India, classes are so large, often 90-100 students, that middle and upper class parents provide tutorials for their children after regular school hours. (In India these programs are called tuitions.) Economically disadvantaged children have no opportunity for such coaching and girls in particular are expected to care for younger siblings at the end of a school day so the bright, economically deprived child, especially the girl child, often falls behind peers and is ineligible for higher studies. The tutorials in English, mathematics, and science, are designed to give bright, aspiring young persons, the opportunity to keep up with their peers. In some cases, remedial work back to the Grade 5 level is needed in this regard. Matriculation examinations are written after successful completion of Grade 9 and study in a special Matriculation Class which is the equivalent of Grade 10 in Canada.

An "illiterate" in Indian society is not only a person who cannot read or write but a person who speaks only one language, thus the emphasis on English, Marathi, and Hindi. English is the country's link language used by most Indians who speak one of the fifteen major languages in the country and is, of course, the language of international business. A knowledge of English becomes increasingly essential for all Indians. Marathi is the language of Maharashtra and Hindi is universally used by most of India's politicians and educated persons. Increasing numbers of poor persons from the south of India are coming to Maharashtra who speak none of the three languages mentioned above. They need survival skills in all three languages to find some place in the working society of Nagpur. As will be explained in detail below, Nagpur is immediately in the centre of the country and increasing numbers of foreign nationals are establishing offices in that area and their employees also need these language skills. Finally, lending libraries as we know them in Canada are almost non-existent in India. They are not free libraries and operate on a subscription basis.

A major difficulty is that academic and professional persons often keep their libraries for their star pupils and do not allow access to them to others. Some of these academics and professionals provide crib notes for examinations and sell them to aspiring students. It would not be unusual, for example, for a student of English language and literature never to have read the literature involved but to have studied from a precis and glosses prepared, photocopied, and sold by persons who have access to the actual books. It is in this way that professional libraries can best serve those persons who wish to read for examinations and take them when they feel qualified to do so. It became clear that my husband's library and parts of my own (English language and literature, philosophy, world religions), could form the basis of this professional library. Subsequently two other professional libraries, philosophy of education, and the history and theology of Christianity were offered to the library by academics from the University of Windsor, and McMaster University. By 1988, then, it was determined that the library would be a learning centre encompassing the three goals listed above, with regular reviews in place to determine the future direction of the Centre. As Dr. D'Souza was coming to describe the project, it appeared to have evolved into "a school where anybody can come to learn anything."The Centre was intended for persons of every class, creed, and community although it would be operated by the Nagpur Roman Catholic Diocesan Corporation. It was hoped at that point that the Centre could be housed in existing facilities, but it soon became clear that it would need to be housed in its own facility which will be described below.

I move now to a description of the geography and demographics of the area in which the Learning Centre has been located, essential for an understanding of the physical dimensions of the project and its probable future expansion. The city of Nagpur is the geographical centre of India. Trains north and south, east and west pass through its central railroad station as do buses. A building site was available on the main north/ south highway and was donated to the Nagpur Learning Centre by the Nagpur Roman Catholic Diocesan Corporation. This site is central in the city proper and within easy walking distance of several of the populations to be served by the Centre especially children in two Hindi-medium elementary schools. It is adjacent to a centre for infants and pre-schoolers with nutritional and health problems. Mothers or the child's primary care giver must accompany the child for treatment and thus provide a potential for outreach work to women. Nearby there is a multi-purpose social service centre which already has an outreach program to women and children connected with providing milk for the babies. Again, mothers or older sisters accompany children to the feeding programs. This location is also very close to two English-medium schools with service clubs whose members might ultimately become tutors in the various Centre programs.

Approximately 64.88% of all persons living in the environs of the archdiocese live in rural settings and are engaged in agriculture. The balance are in the urban area. This is unlike the rest of India where approximately 80% of all persons live in villages. In the Maharashtra districts, 45.77% are literate; 59.40% of these are males, 31.00% are females. In the Madya Pradesh districts, a total of 26.37% are literate; 38.77% of these are males, and 13.08% females. The largest number of persons are Hindus, followed by Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, Jains, Sikhs and others. Many villagers who are tribal persons, especially Gonds, have their own customs but often adopt Hindu practices as well. Throughout the areas diocesan personnel are involved in the establishment of basic human communities. Persons of every creed, caste, and community are brought together to acquire sufficient food, housing, clothing, education, and some leisure for reflection. The diocesan personnel appraise them of their basic rights under the Indian Constitution. A major effort has been and continues to be undertaken to secure clean water for villages, hydro-electricity, and irrigation. In the city of Nagpur itself, there are neighbourhood basic human communities established which are generally facilitated by members of the Catholic community, but engage all persons in observing, judging, and acting upon securing their basic human needs. In both these communities and in the rural ones, major religious festivals and civic holidays are celebrated together, and life cycle events are commemorated in common.

Within the past two years Nagpur has become the central container depository for the country, made possible by expansions to the airport and to the railroad station. Increasing numbers of foreign nationals are making Nagpur their head offices because of its central location and accessibility by rail, plane, bus, and automobile. Cost of living in Nagpur is still considerably below that of New Delhi, Bombay, Bangalore, and Calcutta, India's major commercial cities. Industries in the Nagpur area have doubled in the past ten years and housing starts are numerous to accommodate this increase in production. Persons in slums and semi-slum areas, often rural workers who come to the city hoping to find better employment, are being affected by this need for additional housing. The archdiocese has several programs in place in these areas through its neighbour hood communities, women's office, and the multi-purpose social service centre. It is likely that literacy outreach will become essential.

Construction of the Nagpur Learning Centre

As mentioned previously, it was thought that the Learning Centre could be housed in existing facilities and funds used for material and personnel resources. After a major investigation of possibilities, it was concluded that the Centre needed its own building, in a highly visible public place, apart from any indication that it is denominational. Thus, the site on Kamptee Road on the north/south highway was chosen for construction of the Centre. Since to our knowledge, no resource centre of this exact sort exists in India, or existed at the time the construction was to begin, a Canadian architect, Paul Bolland of Toronto, was asked to provide plans for the Centre. He worked in close collaboratio with his friend and colleague, Peter Rogers, a teacher-librarian with the Hamilton-Wentworth Roman Catholic Separate School Board, and former chair of the Hamilton Public Library Board. Through Mr. Rogers we secured the services of members of the Third World Development Committee of the Canadian Library Association who made recommendations about construction and content of the Centre. All of the aforementioned services were contributed. I contributed $25,000 from my husband's estate to begin construction of the Centre. I had anticipated a matching grant from the Canadian International Development Agency but learned that I could not qualify for that as an individual. After six months of research it appeared that there was no matching grant policy for individual gifts of my sort anywhere in Canada or the United States. Unless I became a registered charitable organization, provincial or federal, I could not secure such grants. At that time I did not see that as feasible since my project was localized. I did approach every Canadian agency working in India, a list of which was provided to me by the Academic Affairs and CIDA officers at the Canadian High Commission, New Delhi.

The only possible, positive response was from World Literacy Canada, which advised me that their funds were accounted for until 1996 and to contact them then. I have done so three times to date and letters and phone calls have gone unanswered. The estimated cost of constructing and equipping the Centre was $250,000 CDN. A devaluation of the rupee occurred which meant that construction and equipping would be $125,000 CDN. It was estimated that it would take three years for necessary approvals and construction of the building. In 1986-87, I agreed to tithe for ten years and have currently contributed $75,000 CDN to the project. An additional $10,000 CDN was received from an Australian benefactor of the archdiocese for the project. A French Catholic funding agency, S cours Catholique, contributed $45,000 U.S. to the project with a similar amount promised for programs once the Centre was up and running. Dr. D'Souza contributed substantially to the project from his private resources and continues to do so. I should mention here that it is Dr. D'Souza's policy in general not to take outside funds for projects. He believes, in principle that programs should be engendered by the people of the community and all costs met by them. However, the Learning Centre project was beyond the means of his local community, and he decided to take "seed" money for the project. The policy of the Centre however is "nothing for nothing" and it must become self-sustaining through persons' paying the costs of their use of the Centre or providing services in kind for those they receive. The re-drawing of plans from the Canadian architect's design to meet Nagpur building standards, and the obtaining of permissions, hiring of contractor, etc., took approximately two years.

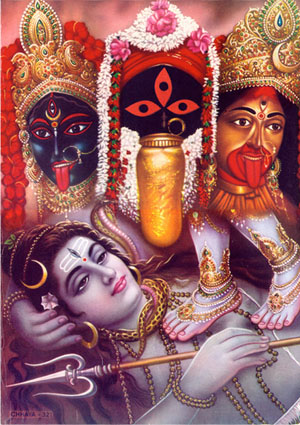

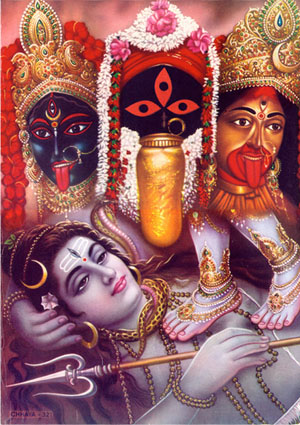

Ground breaking took place on December 8, 1992, and the inauguration of the Centre was on December 22, 1994. A proposed top floor on the building was cancelled bringing the total cost for construction to $90,000 CDN. The Nagpur Learning Centre, which appears on the cover of this report is constructed as follows. Books and resources are stored in a water tight basement room until they are catalogued. The ground floor contains the professional library, the director's office, the computer for cataloguing acquisitions, the computer monitor for users. The desk for the librarian and her assistant are also located here. This area also contains a vertical library of materials connected with international marketing and communication theory. The acquisitions have been so numerous to date that a circular stairway to the first floor is under construction so that additional volumes and resources may be located there. To the left of the ground floor as one faces the building from Kamptee Road there is a reading room for the general public. The room is also equipped with portable tables and chairs and can be used for meetings. Literacy classes are currently being held here. This room is also used for newspapers and serials. An elevator to the other floors is possible but not yet installed. On the first floor above the professional library, is a room for readers of that library. Above it on the second floor is another similar room.

The plan is to install here a bank of twenty-four computers for use with literacy programs, and other tutorials as needs emerge. In consultation with persons involved in English as a Second Language, and adult basic education programs at Mohawk College, Hamilton, Ontario, this was the recommended number of computers for use by any one teacher or team of teachers. In immersion programs in English, the acquisition of writing skills is best done on a computer, according to April Taylor, director of these programs at Mohawk. Above the reading room is a two-storied multi-purpose room. The room can be reached via the interior of the Centre and from the outside. It can be completely sealed off from the rest of the library area. The room seats 150 persons on the main floor and balcony. This room was planned with seminars and meetings in mind and can be rented to other agencies, helping the Centre to become self-sustaining. Some literacy training and programs are currently being held there. The original plan was for living accommodations on the top floor. The intention was to bring persons from rural areas into the Centre for language study and other tutorials. They would require housing. Also, it is the custom in India to provide staff with housing. This is usually a part of their salary and perquisites. In some cases the Indian government requires this kind of housing or construction is not permitted. However, there are hostels for young persons in the Nagpur area and it was eventually decided that building this housing might be premature.It is possible that sending literacy teams into the rural areas is a better approach. The construction of the top floor was put on hold. This unfinished portion appears on the top of the photograph of the building. It is likely now that this floor will be completed but will be used for interactive communicative approaches to language learning. Other portions of the building have central pillars which do not lend to this kind of instruction but do lend to individualized learning at computers or at study carrels. The top floor will be built on beams thus providing the open learning environment conducive to cooperative learning strategies.

Acquisitions and Training

As recommended by the Canadian High Commission in New Delhi, I contacted Donna Thurston of the then External Affairs, Canada. Ms. Thurston agreed to ship my husband's library, publications, and vertical files to the Canadian High Commisison in New Delhi to be retrieved there by Dr. D'Souza and transported to Nagpur. Subsequently she agreed to include an additional ten boxes of material from Dr. John R. Meyer of the Faculty of Education of the University of Windsor. Dr. Meyer and I contributed the costs of UPS services to take the materials to External Affairs in Ottawa. An estimated 5,000 pounds of resources were shipped to the High Commission and then taken to Nagpur. Ms. Thurston made clear that a shipment of this size could only occur once. During a 1990 visit to Canada, Dr. D'Souza and I toured the language laboratory at McMaster University. We saw the laboratory in operation and spent several hours with Tina Furletto of that facility. She advised us that the university was going to dismantle the laboratory in favour of individual audio-cassettes, computer programs, and interactive video programs. She also told us that the university would be offering for sale the English 900 program, a classic in ESL education.

I subsequently purchased this program from McMaster and took it to India. Along with it, I was able to purchase a Stress and Intonation series and a Survival English series of U.S. English. McMaster recommended the purchase of a fast recording device and that students be permitted to take with them a tape of the lesson they have learned so that reinforcing of it could be done at home. In the course of researching aid agencies in India, I discovered the Commonwealth of Learning, housed in British Columbia. While they could not provide me with aid, since they are a government to government organization, they advised me of distance education materials available from the Open Learning Agency of British Columbia. I purchased their English as a Second Language program, and this is now at the Nagpur Learning Centre. In the course of these discussion, I learned that their entire adult basic education program could be purchased and shipped to Nagpur for $5,000 CDN. This purchase is still a possibility. The OLA also offered me their entire program of vocational materials which had to be re-formatted according to the British Columbia Government. The cost of shipping by container would have been approximately $3,500. I contacted vocational schools in New Delhi and in Nagpur but there was only a month in which the decision could be made because the materials were going to be trashed and recycled otherwise. Neither school responded in sufficient time and Dr. D'Souza decided that the programs were not suitable for the Learning Centre, so this material was not secured. A final purchase consisted of the Ontario Academic Courses in English provided through the Independent Studies Centre of the Ontario Ministry of Education. There are three courses, a writing course, Canadian Literature, and English Language and Literature. I also purchased a World Civilisation course and an Economics course at the OAC levels since history and economics are part of the bachelors' and masters' programs in the professional library. These materials were hand-carried to India.

In the course of investigating computer programs in English, I was advised by Mohawk College to contact Karen Taylor at Tralco Educational Enterprises, Hamilton, Ontario, to view Perfect Copy, an English writing program available on computer for three levels, elementary, secondary, and adult. Mohawk uses these programs in their ESL immersion courses. The programs are excellent, as are several others including those which speak the sounds of the language to the user/s. In the process of this inquiry, Ms. Taylor advised me that she had a complete secondary school course of instruction on filmstrips and audio-cassettes, with student work sheets and teachers' manuals, which she was prepared to donate to the Centre. (These programs are now on videotape for North American audiences.) There are literacy programs, writing programs, geography programs, mathematics and science, programs, etc. I accepted the donation and was able to send them to Bangalore, India, via a container being sent there by a McMaster University colleague and his Indian wife. I was also able to send another eight boxes of books, commerce, accounting, and human resources materials, contributed by the Continuing Education Department of McMaster University. The materials were then transported to Nagpur.

From Tralco I purchased an English grammar and usage software package, some basic mathematics and science packages. A student at St. Thomas More Secondary School, Bradley Hubbard, prepared a software program from the Grade 10 Maharashtra State matriculation course in Mathematics. A software package of Strunk and White's approach to English was also acquired along with some world history and geography materials. All of these programs were carried by hand to Nagpur. Dr. D'Souza also has a personal collection of English literature classics on audio-cassettes. Eventually these will be donated to the Nagpur Learning Centre. As Canadian colleagues began to learn of the Nagpur project, I was approached by several of them with their intention of donating their libraries to the Centre if transportation could be found. Eventually I wrote to Mr. Andre Ouellet and made a presentation to his committee reviewing the procedures of Foreign Affairs. I suggested that funds ought to be made available for the transportation of these valuable resources to developing nations. Although Mr. Ouellet and his committee did not see fit to make that recommendation in their final report, he did put me in touch with Dr. Howard Woods, of the Language Institute in Hull, Quebec. Dr. Woods appraised me of the Canadian programs to teach English and I began working with him on the prospect of having him visit Nagpur and teach this method through the Shastri Indo-Canadian Foundation. He had a major commitment in Vietnam for several months but Nagpur was/is a possibility after the Vietnam tour is completed.

On a second visit to the Shastri Indo-Canadian Foundation, they offered to put the Columbia cataloguing system into place in Nagpur and to provide the librarian with instruction on same. They also gave me the materials necessary for the Indian colleagues with whom I was working to visit literacy centres in Canada for three weeks to three months. They were extremely helpful in suggesting ways that individuals from Nagpur could see first hand what is happening in interactive-communicative approaches to second language acquisition. The librarian in Nagpur opted for a program used by members of her religious community, an international organization involved in multi-media projects, including the operating of libraries. The Nagpur personnel have not yet made any applications to Shastri, to my knowledge. They have concentrated instead on programs currently available in India. During a recent trip to India, Dr. D'Souza and I visited the British Council in New Delhi and examined programs they have developed for the teaching of English as a Foreign Language. Many of these programs are designed for Indian nationals who come to Great Britain. Dr. D'Souza also decided to investigate language programs operating in India and began with a trip to the armed forces language centre in Pachmari. He saw there much of what he had seen in Canada but it was new to the team he took with him.

The armed forces personnel recommended that the Nagpur team visit the Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages at Hyderabad. They felt they have the best program in India. The Nagpur team did so, and after intensive consultation contracted for the development of an eighty hour course and for the training of teachers who would deliver this program at the Nagpur Learning Centre. Dr. D'Souza and the team decided to go with the Indian trainers and their methods for the comfort level of the Nagpur tutors. After two aborted starts, the training program for teachers began on February 19, 1996. Twenty persons completed the course. The training itself was inter-active and participatory and retired teachers who took the course were delighted and amazed with the results of this kind of cooperative learning and teaching. A team of four teachers then worked successfully with 25 students from April 7 to June 5, 1996. These students were from the Hindi-medium schools. Dr. Matthew Monippally, Director of CIEFL, visited the course and was extremely pleased with the results. A second course is slated to begin this month. It is an evening course for adult learners. The syllabus for this CIEFL program and a sample lesson plan are appended to this report. It emphasizes spoken English. Plans are now underway for the training of facilitators in Hindi and Marathi.

The director of the Centre, Rev. John Anthony, is in the process of investigating those programs in Hyderabad, Bangalore, and Madras. Unfortunately, tutorials in mathematics and science, apart from those on computer software programs, have not yet taken place although they have been contracted for with a teacher familiar with the requirements of both programs in the matriculation examinations and familiar with using computers for teaching. It is possible that we will ask the Canadian Foundation for World Development to provide us with teachers from Canada who will train Indian teachers in these participative techniques in mathematics and science. It is also possible that we will be able to provide this training through materials developed by TV Ontario. Another option is to invite an innovative educator from Calcutta, Mother M. Cyril, to come to Nagpur to teach teachers the cooperative learning programs she has developed in mathematics and science at Loreto College, Sealdah. I am expecting to teach the general principles of cooperative learning to interested persons on my next visit to India, December 13, 1996-January 25, 1997. It is possible that once they understand these principals, local persons can develop their own teaching strategies in mathematics, science, and other disciplines.

I wish to mention in passing that Mother Cyril is also expert in the use of materials developed by the Open Schools and Open University programs in India. These programs are funded in large measure by the Commonwealth of Learning. In a visit to her in Calcutta I was able to see these programs which are equivalency programs for high school diplomas and university degrees. They are correspondence courses and students are required to sit final examinations. In practice they work poorly because materials are not always received on time, nor marked on time, but in theory they offer excellent materials to students who cannot study in formal educational institutions. Some retired teachers in Nagpur are now using these materials at the secondary school level with high school dropouts. It could be eventually that these programs are offered through the Nagpur Learning Centre. The Centre could also become a site for distance education programs especially in business and commerce which are now being piloted in the Bombay (Mumbai) area. In addition to the materials originally transported from Canada, the principal of St. Francis de Sales College of the University of Nagpur, was asked to provide Dr. D'Souza with the books listed by the State of Maharashtra for required reading for the bachelors' and masters' degrees in English language and literature, history, pure and applied economics, and political science. These materials are currently being purchased by the librarian and/or being photocopied by her where the required books are no longer in print. The acquisition of these materials is a major undertaking since book sellers must be approached individually and orders placed individually.Materials already received from Canada are in some cases on these lists, especially the materials required in English language and literature. Once all books available in India are purchased, an attempt will be made to supplement these books from Canadian sources if they cannot be secured in that country.

The Container Project

As mentioned previously, offers began to come from persons who heard of the Centre and had materials they were prepared to contribute to it. Several academics had libraries which they were prepared to donate if funding could be found for the transport. McMaster University was prepared to sell us its language laboratory at a very good price, although we were constantly learning that they are not worth the effort in terms of usage and repairs. Some persons offered computers, typewriters, and used university, college, and secondary school texts. Beginning in November, 1993, I began investigating container services to India. The costs quoted ranged from $8,000 CDN to $6,000 CDN which seemed far too expensive. In December of 1995, I heard an interview with Mr. Ken Davis of the Canadian Foundation for World Development on CBC. Mr. Davis spoke of the "junk" he has been shipping to developing countries for the past seventeen years. In February of 1996, after a return from India, I contacted Mr. Davis and he was able to secure shipping of a container to Bombay (Mumbai) for $3,500.

In March of 1996 I contracted with him for a container to be shipped to India on April 30th. Transport to Nagpur of the contents would be handled by the team in Nagpur. CFWD is able to give receipts for tax purposes. I contributed $1,000 to the cost of the container. A colleague from McMaster, Dr. Gerard Vallee, contributed $2000. Dr. John R. Meyer of the University of Windsor, contributed $300 toward the cost of transporting 125 boxes of books from the Faculty Association of the University of Windsor to the Scarborough loading zone for the container. Mrs. Anne Cavanaugh of Hagersville, contributed $100 and the Catholic Women's League of St. Stephen's Church, Cayuga, contributed the final $100. Approximately 20 persons contributed time and labour for the packing of books and delivery of them to the loading side.On April 30, 1996, 2,620 boxes of materials were sent to India. Mr. Davis had secured film projectors, slide projectors, a photocopy machine, among other items. The Ontario School Book Exchange contributed six skids of books and an Indian Association in Mississauga contributed ten station wagon loads of books. The Haldimand Libraries (Hagersville, Cayuga, Caledonia) contributed 56 boxes of books. In addition to the materials for the professional library, a large number of general interest books for persons of all ages are in the container. These are to meet the needs of the general public and also to encourage students who take the English literacy course to continue to read in English in their areas of interest. The container arrived in Mumbai on June 11, 1996.

Conclusions and Recommendations

I am convinced that much of the success which has been experienced in terms of this project is because it has been a person-to-person activity, so to speak. Despite the purported donor fatigue in North America and Northern Europe persons were willing and generous with their time, talent, and finances, as I have reported above because they knew their contributions were going directly to where we said they would be going. The absence of committees, bureaucratic structures, and other time and money wasting activities was noted by more than one contributor as something they appreciated. The involvement of local persons in Nagpur in identifying the library and subsequently the literacy and numeracy needs also has helped the project enormously. Literacy can rarely if ever now be separated from personal life management skills and from numeracy. Second language acquisition and all the values associated with that are best achieved as is the acquisition of a first language and personal life skills, that is, in a nurturing, collaborative environment. The CIEFL program in Nagpur is currently producing that environment and those outcomes. Again, I suggest that its simplicity is at the heart of much of the success of this literacy project.

It is likely that other programs could produce the same effect, such as the Laubach method, which is the basis of my own training. From my reading of them, both the Open Learning Agency program and the Language Institute program can do the same. (It is interesting, perhaps, that the Language Institute uses English 900 as a backup for its students.) But CIEFL is working in Nagpur probably because it is designed by Indians for Indians and the various versions of the English language spoken in that country. Dr. Monippally and his colleagues have trained in Great Britain and speak what is often called "BBC English", but they do not demand that accent from their students. Perfection in pronunciation, accentuation, etc., is overlooked in favour of speaking at all and of speaking confidently. Second language acquisition, as it has been experienced by students in the CIEFL program is also "fun" and while it is not a panacea, students preferred this kind of learning to the traditional rote of their other classroom experiences. CIEFL may proceed with training the Nagpur facilitators in more advanced English course offerings, if those needs emerge. Based on the students' responses, to the first eighty hours of training, it is likely that the cooperative method can be used effectively in the other areas of tutorials on the drawing board for the Centre.

The major challenge from my point of view is to put facilitators in Nagpur at ease in using audio-visual materials in their programs. To date, they have used none of the audio-visuals provided from CIEFL, except for some charts, and none from Canada. They have made some flash cards. In addition to teaching cooperative learning strategies to teachers in December-January, I am hoping to help them to become more familiar with the materials that are on hand in the Centre and demonstrate how audio-visuals can enhance their teaching. Several textbooks on using audio-visuals in the classroom have been sent to Nagpur for this purpose. In 1993, the committee on Third World Development of the Canadian Library Association recommended that for at least ten years we make the printed medium the focus of our resources in Nagpur. While I understand this suggestion, primarily because of frequent power failures in the city, I am increasingly convinced that the use of computer software is of equal importance with the printed medium. If we are going to meet the needs of persons who cannot come to classes regularly, we have the medium with computer software which allows them to study at their convenience. There is, in fact, one very successful program in place with street children in Mumbai, doing precisely this. The children are learning English and basic health and hygiene through computer stations throughout the city. This project is being funded by the Swedish government. It is under the aegis of the Tata Social Service Institute. It is my hope that eventually the Nagpur Learning Centre will operate on a twenty-four hour basis via computer terminals, CD ROM programs, and an Internet connection. We now have the mathematics matriculation program on software and others can be developed for the Learning Centre by computer specialists.

On this visit to India I am hoping to take software programs developed for children beginning at age three in reading, mathematics, and science. It ought to be possible to develop similar programs in Nagpur. Indeed, students can be taught how to use computers by involving them in such projects. We already have a test-making software program at the Centre. During the next academic year, I will visit a pre-literacy through Grade 12 program developed in California and being used now by the Wentworth Board of Education in Stoney Creek, Ontario, in a program for adult learners. I think it is likely that after the 80 hour CIEFL course, there would be some students who could undertake the bulk of their studies via a program like this. Again, it is possible that a program based on the Open Schools and Open University programs in India could be developed to meet these specific needs in that country. I am also convinced that we need an Internet hookup at the Nagpur Learning Centre. Given the academic resources alone that are available through this medium, and the downloading possibilities, Indian students studying for diplomas and degrees and for general interest would have tremendous resources at their disposal. The collaborative possibilities via e-mail are enormous. We need not, indeed, I would say we must not wait until 2003 to use other than print as our major resource at the Learning Centre.

Based on my own ten-year experience with the genesis, construction, and present operation of the Nagpur Learning Centre, I would make the following recommendations to persons in Canada promoting world literacy:

a) Funds need to be made available immediately for the transportation of books and other resources to developing nations. Matching grants ought to be available to individuals as well as to registered charitable and non-governmental organizations. Foreign Affairs ought to be encouraged to increase this dimension of its services. The transportation of resources of this sort to developing nations is at least as important as taking Canadian academics to them. The Shastri Indo-Canadian Foundation ought to be encouraged to transport resources as well as personnel. The Canadian Overseas Development Organization should be encouraged to add countries other than Africa and the West Indies to their roster for the transportation of such resources. Their affiliate CODE INC. does provide shipping services overseas but is no less expensive than are for-profit container operations.

b) Department of Defense vehicles ought to be made available for the transportation of such materials. Mr. Ken Davis has managed through the resources of the Canadian Foundation for World Development to have access to training flights and has transported several schools and hospitals to Haiti through these services. This use of training vehicles would be able to transport materials to developing nations without any additional cost to Canadian taxpayers. The current practice is that only relief materials connected with national disasters merit such assistance. The loss of good minds for lack of resources surely also constitutes such kinds of disasters.

c) No matter the programs Canadian personnel would like to put into place in developing countries, the local populace must have the final say about their needs. Canadians who wish to become involved in literacy projects in developing nations, and in India in particular, must do so prepared to learn as much, if not more than they will be teaching. The pace of activity in developing nations is far slower than in North America and Northern Europe. A major cause of this is likely the unemployment and underemployment of many persons in developing nations. The longer it takes to get something done, the longer the employment. Ultimately, indigenous persons must be convinced of the worth of the project and be trained to take it over.

d) Literacy must be seen as directly related to issues connected with poverty and women's liberation. A far more holistic approach to these issues needs to be undertaken. It might be wise for the Federal Government to establish a kind of umbrella "organization" which would allow for all agencies working in any one developing nation to work in integrated ways rather than duplicating efforts. Perhaps CIDA and Foreign Affairs could make such knowledge available through Internet and save hours of researching this information.

e) Finally, in selected areas in developing nations, establish Language Institutes using the materials developed by the Canada Language Institute. Provide training in English and French in these centres for prospective immigrants to Canada, at cost, and provide training for persons in these countries working in basic literacy and second language acquisition.

Respectfully submitted by, ____________________________ Catherine Berry Stidsen, Ph.D. August 15, 1996

Appendix A The Central Institute for English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad Syllabus prepared for the Nagpur Learning Centre

1) AIMS: This course aims at helping learners to gain confidence in spoken English. It also seeks to enhance their ability to read and write in English.

2) SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES FOR SPEAKING AND READING: The course helps learners to gain confidence in using English, develop over all fluency in the language and communicate effectively in it. Students are expected to listen to and respond appropriately when spoken to in English. They should be able to participate in day to day conversations, arguments, debates, etc. They are expected to report incidents in their lives and narrate those experiences. They are to be able to read aloud pausing appropriately at punctuation marks.

3) SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES FOR WRITING: Learners are expected to become aware of the size and shape of English letters. They are to be able to write neatly and legibly. They should be able to write small paragraphs on a topic of interest and this should be done in a coherent and organized manner. They are expected to know the differences between reports, notices or announcements, application forms, covering letters, and a curriculum vitae.

4) COURSE CONTENTS: A) Speaking Students will do the following: --practice introductions and greeting formulas --practice reading aloud newspaper headlines, magazine stories, simple news stories, reports, letters --engage in structured conversations --learn polite expressions, such as making requests --engage in conversations connected with buying, selling, bargaining, apologising, accepting apologies, refusing apologies, complimenting, agreeing, disagreeing, giving directions, asking for information --give short prepared speeches --give short ex tempore speeches --learn the use of a dictionary for pronunciation, spelling, meanings, usage --practice narrating stories and incident --engage in simulations and role plays --read and enact plays --debate --participate in panel discussions COURSE CONTENTS: B) Writing Students will do the following: --practice printed and cursive letters and numerals --understand and use punctuation marks --use dictionary for understanding usage --use book of grammar for resource --use newspaper headlines for comprehension --write short sentences --summarise --take and make notes --do pr cis writing --make drafts of notes, notices, appeals --write short letters, letters of regret, acceptances of invitations --write letters of application --write reports --understand persuasive writing --edit, organize, and correct a peer script

Appendix B Sample Lesson Plan, Nagpur Learning Centre

9:30 a.m. Opening exercises, rotated among students 9:35 a.m. One minute speech from each student. In the previous lesson students are assigned topics with which they are familiar and asked to prepare a speech for the next day. Peers may suggest improvements to the speeches.

10:00 a.m. New topic from the syllabus is introduced. No material is repeated to keep students interested. One facilitator does the oral instruction. A second writes on the blackboard during the instruction. Others move about the room helping with note taking, etc. Facilitators ask questions concerning content throughout this period of instruction and students are urged to volunteer answers. Facilitators and peers help volunteers with correct structure, stress, and intonation.

10:30 a.m. Students move into small groups to reinforce large group instruction. Groups usually consist of four to five persons and are organized according to the states from which the students come, e.g., Hindi-, Marathi-, Telegu-, Punjabi-speaking, etc. Students are required to speak in whole sentences. Peers are encouraged to work with each other in acquiring the new information. They complete not compete.

11:00 a.m. Group activities vary according to the point in the syllabus. Written work may be undertaken, e.g., preparing an announcement of a lost pencil case. Substitution drills may be used at this point. Sometimes the group is assigned to tell a story with each member taking a part in the telling. Pictures are used to help with the construction of the story. Role plays, simulations, learning to use a dictionary, may be assigned. Usually there are some play-way exercises that conclude this portion, such as verbal or visual puzzles to be solved, Class is dismissed at 11:30 a.m.

Observation. Team teaching helps to avoid boredom and routine. Groupings permit students to work with several facilitators. There is no pressure put on students. Collaborative learning gives them the nurturing situation which encourages them to do so. As students become more proficient they become the facilitators of their own learning. Teachers speak less and less and students question and speak more and more. The method is excellent.