No Exit

(Huis Clos)

Presentation for Major 20th

Century Writers Class

Octobe2000

Jerry Hartman

Credits

Hanging Artwork by Stephanie Hartman

Contents of Presentation

(Brief) Entrance

Performance

Introduction to Huis

Clos Ý(No Exit)

Early Biography of

Sartre

Major Works of

Sartre

Existentialism

Reasons the

characters in No Exit are in Hell

The Torture Circle

ìHell is other

peopleî

LíEtre et le

Neíant (Being and Nothingness)

The Problem of

Other

Second Empire

Furniture (handout)

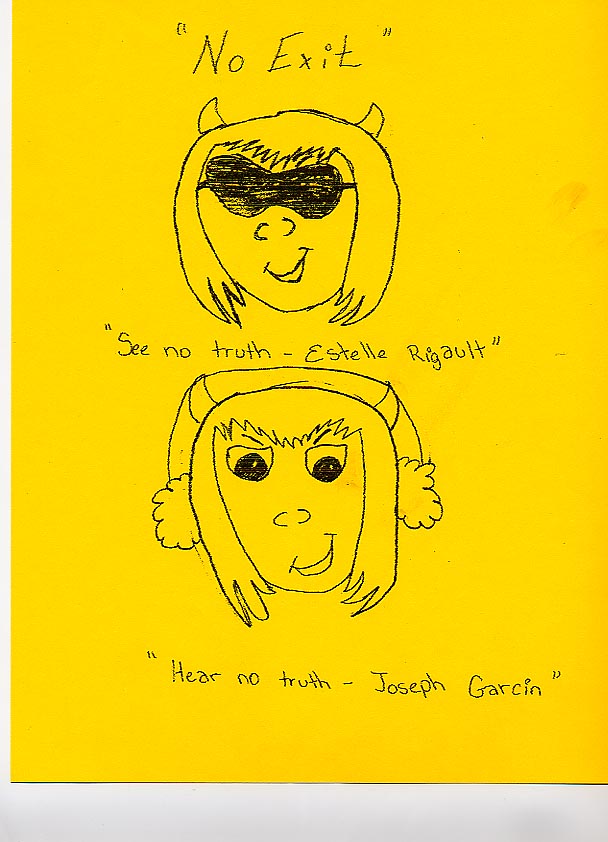

ÝìSee No Truth, Hear No Truth, Speak No

Goodî

Works Consulted

Excerpts from

WorksÝ

A Final Note

Opening

Performance

Enter the room and methodically

post ìNo Exitî signs on walls.Ý Do the

sidewalls first, then the front wall.Ý Finally,

quite deliberately look at the door and post the final sign there.Ý Then tape an ìXî across the doorway barring

exit from the room.Ý

Return to the front of the room.Ý

Switch on the two reading lights, which are pointed toward the sign now

hanging on the front wall.Ý Slowly look

across those in the room.

HelloÖand welcome.Ý Welcome

ìabsentees.îÝ Welcome toÖ. well

you know where we are.Ý I would say,

ìmake yourself comfortable,î but why even bother?Ý Even still, would you mind if I (start to remove jacket) took

off my coat?

Questioner # 1 (Joanne): (demurring) As a matter of

fact, I do mind.

Of course, very well thenÖ

Questioner #2 (Holly): But it is so stuffy in here.

I would say we will get used to it, but why pretend?Ý (give a pretentious smile)

(slowly looking across the audience, very somber and serious) Going forward, you

will refrain from blinkingÖ

Huis Clos ‚ No Exit

Literal translation ‚ ìclosed doors;î more specifically ìbehind

closed doorsîÝ

ÝÝ

British interpretation -Ý ìIn Cameraî referring to a court in session.

First presented in Paris May 1944.

Initial run interrupted by the uprising that drove the Germans out

of Paris.

Second ìfirst nightî September 20, 1944.

Marked the triumph of what was known at the time as ìresistentialisme.î

Play was written when Marc Barbelat, a printer, asked Sartre to

write a play for his wife and another actress.

Guidelines:ÝÝ

ÿ easy to produce

and take on tour;

ÿ No changes in

scenery;

ÿ Only three actors.

Another consideration ‚ ensure that none of the three actors felt

jealous of the two others by being forced to leave the stage and let them have

all the best lines.Ý

Hence the idea of a situation where the three characters would be locked

up together ‚ a cellar during an air raid was considered.

Ý

Albert Camus had attended the opening of Sartreís only previous play

Les Mouches (The Flies).Ý Camus

had told Sartre of his passionate interest in theatre.Ý

Sartre asked him if he would like to both produce No Exit and take

the role of Garcin.

Camus declined on the grounds he was too inexperienced to direct a

play for the Parisian stage.

Biography

Sartre was born in 1905.

His father died when he was very young.

Sartre was raised in the household with his maternal grandfather,

who had a deep influence on him.

In his autobiography, The Words (1963), Sartre stated his

career as an author was a response to his childhood experiences of rejection.

He graduated from the Ecole Normal Superieure, Paris, in 1929.

He received a doctorate in philosophy.

He went on to teach in various lycees, or secondary schools, in

LeHavre, Lyon and Paris until 1945.Ý

He was a key figure among French intellectuals who resisted the Nazi

occupation.

He spent nine months as a prisoner of war.

Sartre gave up teaching after the war and devoted all his time to

writing and editing the journal Les Temps Modernes (Modern Times).

He emerged as the leading light of the left-wing, the supporters of

which could be found at the CafÈ de Flore on the left bank.

He eventually broke with the communists.

His lifelong companion and intellectual associate was Simone de

Beauvior.

Works

of Sartre

A philosopher, literary figure and social critic, Sartreís literary contributions

and philosophical tenants were delivered through novels, short stories and

plays, as well as through academic treatises.

Among his first works (printed in 1936) were:

LíImagination (Imagination) a history of the theory of imagination;

And

La Transcendence de líego (The Transcendence of the Ego) a

phenomenological account of consciousness.

La Nausee (Nausea) is a novel that was published in 1938.Ý It follows the main character, Roquetin, on

a metaphysical journey of discovering his being and aloneness in the

world.Ý These realizations give rise to

anguish and nausea in the struggle with the problem of meaningful existence.

Sartreís major philosophical premise, LíEtre et le Neant

(Being and Nothingness), was printed in 1943.Ý

It explored Sartreís theories of being, consciousness and relations with

others.

His essays on literature include What is Literature? (1948)

in which he argues that literature must be political.

A later work, The Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960) is a Marxist

analysis of social existence in which he attempts to explain how the freedom of

the individual is related to history and the class struggle.

<This left view is debated as being at odds with the

individuality of Sartreís existentialism.>Ý

Existentialism

Is concerned with the problem of existence:

ÿ Who we are;

ÿ Why are we here;

ÿ How we make

meaning in our lives.

No ìpredestinationî

Humans must decide for themselves what their actions will be, then

take full responsibilities for their choices.

Only by assuming this freedom can one live authentically.

Term not coined until Sartre and Camusí writing were published.

A philosophical, literary and artistic movement that flourished in

the late 1940s of postwar Europe centered in Paris.

As a movement in French thought it actually starts during the

aftermath of the First World War.

While deemed ìexistentialistî in retrospect, the philosophy dates

back to the 19th century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard is the first to break with the tradition, in place since

Plato, that the highest ethical good is the same for everyone.

Kierkegaard insisted that the highest good for the individual is to

find his or her own unique vocation.

ìI must find a truth that is true for meÖthe idea for which I can

live or die.î

In general existentialism emphasizes individual existence,

individual freedom and individual choice.Ý

The importance of passionate individual action in deciding questions

of both morality and truth.Ý

ÿ

While not having read any of Sartreís later, leftist,

writings, it is difficult to reconcile the individual nature of existentialism

with the collective nature of Marxism.

SUBJECTIVITY - the understanding of a situation by someone involved

in that situation is superior to that of a detached, objective observer.

That point plays deeply into No

Exit and the Sartrian concept of ìbeing-for-others.î

Sartreís existentialism is atheistic, as opposed to Kierkegaard who

advocated a ìleap of faithî into a Christian way of life.Ý Kierkegaard acknowledged that this ìleapî

was full of risk, but felt it was the only commitment that could save the

individual from despair.

Sartre declared that human beings require a rational basis for their

lives but are unable to achieve one.Ý

Thus Sartre is pessimistic and finds human life is a ìfutile passion.î

Rejecting despair however, Sartre believed that life, and the

choices one makes, is what provides meaning.Ý

Quote from Sartre (1946) in a speech ëForgers of Mythsí:

ÝÝÝÝÝÝ ìMen are not created

but create themselves through their choices.îÝÝÝ

Death is only the negation of oneís possibilities.

A theme found in No Exit ‚ once the characters have passed from the

world their lives are summed by others based on their actions while alive.Ý

Torture Circle

Inez is the one who tortures Garcin ‚ makes him face his cowardice;

Also Inez prevents Estelle from thinking of him as a brave man of principle,

this is what Garcin desperately needs.

Estelle is the one who tortures Inez ‚ she will not allow Inez to be

her looking glass.Ý Estelle only has

eyes, need for Garcin.Ý Estelle seeks to

eliminate Inez from the setting in order to have Garcin.Ý This is revolting to Inez and creates a

rivalry, in the mind of Inez, between Garcin and Inez.

Garcin is the one who tortures Estelle ‚ she is in desperate need of

a man to hold and love her.Ý She wants

to be thought of as the innocent victim of circumstances rather than one who

murdered her own child.Ý Since Inez will

not allow Garcin the pleasure of dishonesty in viewing his own life, Garcin is

unable to afford the same to Estelle.

None of the characters is able to see the others as they want/need

to be seen.Ý

When afforded the opportunity to leave through the open door, none

take it.ÝÝ Again, even in death, these

characters are afforded a choice.Ý Once

they choose not to leave, their hell becomes a chosen one.Ý

All three are then locked in a stalemate of perpetual torture.

Reasons for being

in Hell

Acts committed while on earth:

ÿ Garcin emotionally

and physically abused his wife.

ÿ Inez drove her

cousin to his death and led her lover Florence to commit murder/suicide.

ÿ Estelle drowned her

baby simply because she did not want it; this drove her lover to suicide.

Failure to live authentically:

ÿ Garcin and Estelle

refused to accept the choices they made on earth, forever promoting and

believing images of themselves that they knew were not true.

ÿ Inez knew what she

was, ìIím rotten to the core,î but continued to treat people in a sadistic

manner.

Inez then, did live authentically, if despicably.Ý Thus her hell may not be as torturous as for

the other two.Ý I.E. if it is indeed

true that she ìcanít get on without making people suffer,î she is well situated

in her state in this room.Ý For all

eternity she will now be in a position to make Garcin and Estelle suffer.Ý Could this is her ërewardí for having lived

ëauthenticallyí?ÝÝ

Inez also states ìI prefer to

choose my hell; I prefer to look you in the eyes and fight it out face to

face.î (P 23)

ìHell is other

people.î

Most simple level ‚ hell is relation with other people.

ÿ Sartre did not

believe that relationships between people were always doomed to fail.

ÿ ÝSartre did not view all of humanity as

floundering in a living hell.

Next level, hell is other people in so far the presence of other

people reminds us of how inadequate our own behavior has been.Ý

This happens when people refuse to make choices, take responsibility

for those choices, and then have to face themselves through others as the sum

total of those choices.

Garcin - Gomez and the others in the pressroom summing Garcin up as

a coward.

<Interestingly at the start of the play Garcin states to the

Valet, ì Iím facing the situation, facing it.îÝ

Also, referring to the furniture and his being accustom to living among

furniture he didnít relish, ìBogus in bogus, so to speak.î>

Estelle ‚ mortified as Olga tells Peter about her killing the child.

Inez ‚ to a lesser degree, as Inez knows that while she may have

seduced Florence and taken her away, Florence was miserable in the situation

and killed them both as a result of being in the situation. The other person

was ìin hellî as a result of being with Inez.

<What about redemption?Ý

Cannot one who has made bad choices in the past be redeemed?Ý How does this play out particularly as the

existentialist does not accept predestination?Ý

Is one condemned based on one bad choice? >

LíEtre et le Neíant

(Being and

Nothingness)

Two aspects of human beings:

ÿ ëIn-itselfí

(en-soi)

ÿ ëFor-itselfí

(pour-soi)

Subject/Object relationship with oneself.

The problem of the ëOtherí

The ëlookí

ëBeing-for-othersí

ÝëIn-itselfí:

ÿ Is the ëbeingí

aspect of something or someone;

ÿ It is inactive,

inert, the object-like part of a person.

ÿ Being without

knowledge of itself.

Because the ëin-itselfí lacks self-consciousness it necessarily lacks

freedom as well.

Examples ‚ a table, a tree, a rhinoceros.

ëFor-itselfî ‚ is what distinguishes humans from other forms of life by the

fact that it possesses a reflective consciousness.

Ý

The ëfor-itselfí (unlike the ëin-itselfí) is aware of itself and the

objects around it.

ëFor-itselfí is not its own being in terms of physical mass or

shape.

It is nothingness ‚ it is the origin of freedom and origin of human

existence.ÝÝ

The freedom of the ëfor-itselfí is expressed through its choices and

acts.

This freedom is what defines the ëfor-itselfí and the person.

The subject like ëfor-itselfí is envious of the inactive,

object-like ëin-itself.í

The ëfor-itselfí is always trying to become thing-like.

ìI am thinking about Cathy.î

Subject = ìIî

Object = ìCathyî

I can think about Cathy because she is a separate entity.

I can view her objectively.

ìI am thinking about myself.î

Subject = ìIî

Object = ìmyselfî

Because I am both I cannot have an outside view of myself.

The inability to see myself objectively leads me to rely on others

to define who I am.

The

Problem of the ëOtherí

I am a subject that can assert my freedom by organizing things and

people as objects.

ëOthersí are also subjects ‚ they also possess a reflective

consciousness that can perceive me as an object.

This robs me of my freedom.

<This, at times, may not be rejected.Ý Witness Estelle and her desire to be had by Garcin. >

It is through human relations that a person and another engage in a ìbattle

of consciousness,î each acting as a subject in an attempt to capture the other

and make them into an object.

One does not want to be captured as an object, forever defined by

what the subject views.Ý <Garcin by

the men in the pressroom; Estelle by Peter. >

Yet it is necessary to be viewed by ëotherí as we would have no idea

of who we are.Ý <Estelle accepting

the offer for Inez to be her mirror, then coiling back because her image was so

small. >

ìOur acts inevitably escape us : they put us at the mercy of others

since we are only defined by our acts and our acts are defined by other

peopleís reaction to them.î

ìWe donít do what we want and yet we are responsible for what we

are.îÝ - Sartre

Estelle ‚ seeks to be objectified (perhaps slightly above) in

offering herself to Garcin.Ý She does

not want to become nothingness.Ý ìSurely

Iím better to look as than a lot of stupid furniture.î

Garcin ‚ trys to escape objectification.Ý Wants Estelle/Inez to see him as a man of principle.Ý Does not want to be labeled as a

ìcoward.îÝ Inez will not release him :

ìYouíre a coward,

Garcin, because I wish it.î

The

ëapprovalí of Estelle is of no value to him, for he knows it is false and only

granted with her own gain (to be objectified by him) in mind.

InezÝ -- Estelle wants to turn her into

nothingness.Ý ìDonít listen to her.ÝÝ She has no eyes, no ears.Ý Sheís nothing.î

Also note that the issue Inez had with the world was not how others

perceived her, but that the room she shared with her lover was let to a heterosexual

couple who made love on her bed.Ý In

essence erasing her existence there.

ÿ In an effort to

know themselves, the characters attempt to be seen as the objects they believe

themselves to be and to escape any objectification that contradicts their view.

ÿ The ëlookí of the

other two is the method of objectification.

There is no escaping the ëlookí

ÿ always light;

ÿ no sleep;

ÿ no eyelids.

No mirrors to see oneís self or oneís own reflection ‚ must be

looked at by others.

Second Empire Furniture (handout) ‚ the type of furniture in ìNo

Exitî hell.Ý

ìSee No Truth, Hear No Truth, Speak No Goodî drawing unveiled.Ý

Ý

v This is my 11 year

old daughters Dante-themed interpretation of the three eternally linked

characters in ìNo Exit.î

v Estelle : See No

Truth

v Garcin: Hear No

Truth

v InezÝÝÝ : Speak No Good

Works Consulted

Banham, Joanna (Ed). Encyclopedia of Interior

Design. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997.

Dempsey, Peter. The Psychology of Sartre.

Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 1950.

Fell, Joseph P. Emotion in the Thought of Sartre.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1965.

Howells,

Christina (Ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Sartre. Cambridge: Press

Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1992.

Jeanson, Francis. Sartre and the Problem of

Morality. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

LaCapra, Dominick. A Preface to Sartre.

Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Lein, Stephanie. ìSartrian Existentialism in ëNo

Exití.î 9 October 2000. <http://www.honors.org/AHR/AHR00/sartre2.html>

Murphy,

Julien S. Feminist Interpretations of Jean-Paul Sartre. University Park,

Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Thody, Philip. Sartre : A Biographical

Introduction. London: Studio Vista, 1971.

Warnock, Mary.Ý

Sartre: A Collection of Critical Essays. Garden City, New York:

Anchor Books, 1971.

Excerpts from Works

It is important to repeat the assumption of Sartreís

famous analysis of "concrete relations with others," which finds its

dramatics summation in the play No Exit (Huis Clos): Hell is other

people. Not only is the concrete individual identified with the for-itself for

the purposes of the analysis. The for-itself is presented as pure and total

freedom, which allows of no internal alterity or overlap with the

"other." I am not seen as always already decentered by an

"other" within me. Nor am I both the same as and different for the

"other."

A Preface to

Sartre (P. 135)

What is to become of the supreme moral value of

generosity, which, according to Sartre, lies closest to freedom? It would seem,

indeed, that if original alienation is the alienation caused by the simple

materialization of freedom, then there is no way out; as in No Exit, the

last word would be "continuons" and now even more desperate

because this would be a cosmic No Exit, extending out to the whole of

the relation of man to the world since this relation can never dispense with

matter.

The Cambridge

Companion to Sartre (P. 189)

Behind this lies the principle that the power of an

emotion is directly proportional to the immediacy of the perceived stimulus.

First the threat is veiled by distance, and the emotion is "delicate."

As it approaches the obscuring veil is cast aside, only to be replaced by a

very much thicker veil in the form of a vehement emotion whose purpose is

magical annihilation of the threat.

Sartreís play No Exit affords an

illustration. Inez, Garcin and Estelle find themselves in hell. The disaster is

indeed "total." But as the drama begins our three characters have

caught "only an imperfect glimpse of it." The story, then, consists

in the gradual revelation of the eternal hopelessness of their situation. They

try various means to ameliorate their plight ("If we bring our specters

out into the open, it may save us from disaster, says Garcin). For a while they

attempt to treat each other civilly, to remain calm: in short to use rational

means. But as the realization of the magnitude of their misfortune grows, their

emotional reactions, at first delicate, mount in intensity. Finally the

"veil" is thrown aside, and the disaster which their emotions could

not quite hide is directly revealed. They have no means to save themselves, and

they now know it explicitly. "knives, poison, ropes -- all useless."

They give themselves over to hysterical laughter. But even this vehement

emotion -- their response to the recognition of the absolute and eternal futility

of their circumstances -- is useless. Their emotion transforms nothing but

themselves, and themselves only momentarily. "Their laughter dies away and

they gaze at each other." as the curtain falls.Ý Emotion, then, seem for Sartre responses to extreme

situations, even when an emotion first appears either "delicate" or

"positive."

Emotion in the

Thought of Sartre (P. 26-27)

(Huis Clos) was apparently written with purely aesthetic

considerations in mind. (Sartre) had been asked by Marc Barbezat, the printer, to

write a play for his wife Olga and for another actress called Wanda. It would

have to be easy to produce and take on tour, with no changes in scenery and

only three actors. Sartre was also asked to ensure that none of the three

actors felt jealous of the two others by being forced to leave the stage and

let them have all the best lines; consequently he began to think in terms of a

situation where three characters would be locked up together -- in a cellar

during an air raid, for example. Suddenly, he hit upon the idea of locking them

all up in Hell, and the play was made. Albert Camus had come to the first night

of Les Mouches and introduced himself to Sartre. He was passionately

interested in the theatre, and Sartre asked him if he would like to both produce

the play and take the part of Garcin. Camus eventually declined, on the grounds

that he was too inexperienced to direct a play for the Parisian stage, and was

replaced by a professional director called Raymond Rouleau. Huis Clos

had its first production in May 1944, at the Theatre du Vieux Colombier, and

its initial run was interrupted by the uprising which drove the Germans our of

Paris. It was the first play to be performed in Paris after the Liberation, and

its ësecond first nightí, on 20 September 1944, marked the triumph of what was

known at the time is resistentialisme.

The immediate success of Huis

Clos offers a microcosm of the mixture between popularity and notoriety

which Sartre enjoyed in post-war France. His critics found it morbid; his admirers

brilliantly written and morally challenging; and the public at large

stimulating as well as occasionally annoying by its metaphysical pretensions.

It has, however, continued to prove extremely successful as a play, with

countless amateur as well as professional productions to its credit. The gloomy

picture which it gives of human relationships is, in fact, ambiguous, and its

meaning can vary according to the context in which it is studied. Three people

are in Hell, and it is reasonable to assume that they are being punished for

something. Garcin, the only man, has based his whole life on the assumption

that he was a hero. Yet when the crisis broke and he had to stand by his

principles, he ran away. His punishment lies both in his knowledge that the living

will always think of him as a coward, and in the perpetually haunting

possibility that one of the dead with whom he is now incarcerated, Estelle,

might perhaps be persuaded to change something in this verdict by thinking of

him as a brave man. She would be quite happy to do this, if he would agree to

think of her as the innocent victim of circumstances rather than a frivolous

and immoral woman who murdered her own child. Their exchange of mutual bad

faith would be quite satisfactory were it not for the third person with them,

the lesbian Ines, who has caused her own and her girl friendís death by a

suicide pact, after driving this girl friendís husband to kill himself. Simply

by looking at Garcin and Estelle, she can use her knowledge of what they are really

like to destroy the complicity between them; and since the first half of the

play consisted in a general confession, each of the three people knows just

exactly how bad the other two have been. Their punishment lies in the fact that

Garcinís presence will always destroy the potential affair between Ines and

Estelle; while Estelleís presence will always create rivalry between Ines and

Garcin, preventing the two ëmaleí characters from establishing any kind of modus

vivendi. Meanwhile the presence of Ines will always prevent any pact

between Garcin and Estelle. The powers that be, Garcin, realizes, are

economizing on manpower. Each person is a torturer for the people with him.

In this moral interpretation of the

play, Sartreís famous statement that ëHell is other peopleí takes on a fairly

precise and limited meaning. Other people are Hell only in so far as their

presence reminds us of how inadequate our behavior has been. If, like

Corneilleís Rodrigue, we could declare : ëJe le ferais encore si jíavais a le

faireí, other peopleís critical glances would not matter. We should be able to

defy them because we knew that we had done the right thing, and this is

certainly how the Orestes of Les Mouches or the Goetz of Le Diable et

le Bon Dieu would act. It is when we read LíEtre el le Neant that Huis

Clos takes on a much less obviously moral significance. There, Sartre

asserts quite categorically that ëconflict is the original meaning of myself as

I am for other peopleí, that ëmy original fall resides in the existence of

other peopleí, and it does seem in this respect as though the boundary

situation described in Huis Clos is privileged in the sense that it

reveals the essence of manís relationship with his fellows. One critic asked

whether the situation would be the same if the three people incarcerated were a

general, a nun and the mother of a family, and it is probable from Sartreís

general attitude towards society that three such people would be so steeped in

bad faith that their mask of respectability would soon disappear. But even if

Che Guevara, Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Simone de Beauvoir were locked up together,

they would still, according to LíEtre el le Neant, be unable to avoid

making their lives a hell. "Enter not in the judgment of Thy servant, O Lord,

for in Thy sight shall no man living be justifiedí is a phrase that expresses

the impossibility for a Christian of ever feeling that he has escaped from the

burden of original sin which weighs down even the most virtuous; and Sartreís

apparent dismissal, in LíEtre el le Neant of the possibility that anyone

should ever have an authentic and positive relationship with his fellows seems

to indicate that for him, as for Newman, some ëterrible aboriginal catastropheí

lies at the root of the human adventure. If LíEtre el le Neant can be

seen as the summa of the comprehensive analysis which he offers of the human

condition, Huis Clos is a kind of instant catechism in which simplified

answers are given to a number of basic questions about the nature and destiny

of human beings.

It is also an interesting

coincidence that the ethic which can be inferred from Huis Clos should

be a rigorous as any put forward by Calvin, John Knox or the Pascal of the Provinciales.

"We donít do what we want and yet we are responsible for what we areí

writes Sartre in Quíest-ce que la Litterature?, and the curious mixture,

characteristic of extreme Protestantism, between insisting that people do their

duty and telling them that they will never attain virtue, is perhaps one of the

most troubling features of this play. We have no one to blame but ourselves,

and non of the characters can seek refuge in their good intentions; but even a

Garcin who had lived up to his own ideals would still be tormented by Ines and

Estelle. The production of Huis Clos established Sartre as a major

dramatist, just as the publication of La Nausee had marked him out as an

outstanding novelist. A year earlier, in 1943, the appearance of LíEtre el

le Neant had been greeted by a disconcerting silence. It was not until 1945

that it became the most widely discussed work of contemporary philosophy, and

one which had attained , by 1957, its fifty-fifth edition.

Thody,

Philip. (1971). Sartre : A Biographical Introduction. London : Studio

Vista Limited. (P. 64-66)

A Final Note

Well, if you have made it

this far would you be good enough to indulge me a few personal notes?Ý This presentation was for a class in the

School of Continuing Education at New York University.Ý Perhaps I am unduly flattering myself, but

if somehow you have found merit in this effort and would like to use it in some

way, please feel free to do so.ÝÝÝÝ

I would like to thank my

daughter for her artwork (she gave a fresh perspective to her ìPopî as he

fretted over the deep meaning of the play).Ý

I would also like to acknowledge the value I received from the work

written by Stephanie Lein and cited above.Ý

I found it online and reading and rereading it (on a plane to and from

Houston while in my corporate identity) is what finally made this philosophy

click for me.Ý Finally, to my fellow

students, who at least feigned interest during my time in front of them and to

our professor who makes every class an adventure, thanks for putting up with

the only guy and the only one over forty in the class.Ý Iím a pretty luck old dude to have had the

company of and to have learned so much from such intelligent and interesting

women these past three months.ÝÝÝÝ

ÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝ JerryÝÝÝ

ÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝ ÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝDecember 3, 2000

ÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝÝ

ÝÝ