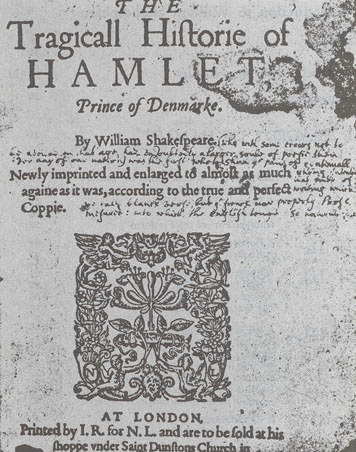

Of all Shakespeare's characters, that of Hamlet is generally thought to be the most difficult to be reduced to any fixed principle. With the strongest purpose of revenge, he is undecided and inactive; in the middle of the gloom of the deepest melancholy; and while he is described as a passionate lover, he seems indifferent about his affections.

The basis of Hamlet's character seems to be an extreme sensibility of mind, having a tendency to be strongly impressed by its situation, and overpowered by the feelings which that situation excites. His misfortunes were not accidental, they were as reflections only to irritate that arose from his uncle's villainy, his mother's guilt, and his father's murder. Thus Hamlet's character was formed by nature and modeled by situation. Finding such a character in real life, of a person endowed with feelings so delicate as to border on weakness, with sensibility too exquisite to allow or determine action, Shakespeare has placed it where it could be best exhibited, in scenes of wonder, of terror, and of misconduct, where its varying emotions might be most strongly marked among the imagination, and the war of the passions.

Had Shakespeare made Hamlet pursue his vengeance with a steady determined purpose and led him through difficulties arising from accidental causes, but not from doubts and hesitations of his own mind, the anxiety of the spectator might have been highly raised, but it would have been anxiety for the event and not for the person.

From the very opening Hamlet is delineated as one under the domination of melancholy, whose spirits were overcome by his feelings. Grief for his father's death, and displeasure of his mother's marriage, prey on his mind. He does not attempt to resist or combat these impressions, but is willing from the contest.

-

Oh! That this too too solid flesh would melt,. . .

-

The time is out of joint; oh! Cursed spight,

That ever I was born to set it right!

-

To be, or not to be, that is the question.

-

The spirit that I have seen

May be the devil, and the devil hath power

T' assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps,

Out of my weakness and my melancholy,

Abuses me to damn me.

Shakespeare, wishing to elevate the hero of his tragedy, and at the same time to interest the audience on his behalf, throws around him, from the very beginning, the majesty of melancholy, along with that sort of weakness and irresolution which frequently attends it.

The attitude of Hamlet towards Ophelia is without doubt the greatest of all the puzzles in the play. The difficulty is not that, having once loved Ophelia, Hamlet ceases to do so. This is explained by his mother's conduct which has put him quite out of love with Love and has positioned his whole imagination. The exclamation "Frailty thy name is woman!" in the first soliloquy, embraces Ophelia as well as Gertrude, while later he accuses his mother with destroying his capacity for affection:

-

such

an act

That blurs the grace and blush of modesty,

Calls virtue hypocrite, takes of the rose

From the fair forehead of an innocent love

And sets a blister there.

-

At such a time I'll lose my daughter to him.

As a child Hamlet had experienced the warmest affection for his mother. Without his being aware of these ancient desires ringing in his mind, he is struggling to find conscious expression and use of energy to repress this mental state he himself so vividly depicts. His resentment against women is still further inflamed by the hypocritical prudishness with which Ophelia follows her father and brother in seeing evil in his natural affection, an attitude which poisons his love in exactly the same way that the love of his childhood must have been poisoned. The intensity of Hamlet's repulsion against woman in general, and Ophelia in particular, is a measure of the powerful repression to which his sexual feelings are being subjected.

Hamlet's call for duty to kill his stepfather Claudius can not be obeyed because it links itself with the unconscious call of his nature to kill his mother's husband. Hamlet's exclusion from the throne is when Claudius has blocked the normal solution for Oedipus complex. In his moral duty, to which his father exhorts him, to put an end by killing Claudius, his unconscious does not agree to be identified with Claudius in the situation. His remorse is ultimately because of his failure. Killing his mother's husband would be equivalent to committing the original sin himself.

In Shakespeare's tragedies it is usual for the chief survivor to sum up the story and to give a farewell to the hero with a final comment on his character. Shakespeare couldn't finish his play by saying that Hamlet is a failure, a dreamer, a philosopher or too sensitive to carry out a ruthless deed. Far from it, Fortinbras's words commemorating Hamlet are:

-

Let four captains

Bear Hamlet like a soldier to the stage,

For he was likely, had he been put on

To have prov'd most royally: and for his passage,

The soldiers' music, and the rites of war

Speak loudly for him.

Take up the body; such a sight as this

Becomes the field, but here shows much amiss.

Go, bid the soldiers shoot.