Thanks for coming in costume with literary and culinary treats to the Literary New York Halloween Party at the NYU Bookstore October 31, 2011 and making it such a success!

Major Authors: New York Writers

Fall 2011

LITR 1 DC 6282. 001 September 12 - October 31st

LITR 1 DC 6282. 002, November 7 - December 19th

New York University

McGhee Division

4 Credits. 2 credits for each short semester.

Professor Julia Keefer

julia.keefer@nyu.edu

https://pages.nyu.edu/keefer/twenty/contnyc.html

212-734-1083

Office Hours: Before and after class, Wednesdays at the NYU bookstore between 4-6,

Saturday mornings at Coles, before and after literary readings and optional NYC events,

Online all the time

Course meeting time: Monday evenings 6:30-8:50 in the Reading Room on the 9th floor of the Bobst Library

Semester I: September 12 – October 31st

Semester II: November 7 – December 19. Meeting in the lower level of 7 East 12.

The first section is not a prerequisite for the second semester. You may register for either or both semesters. Community literary reading times may vary.

No Pre-Requisites. Students from CAS, Gallatin, and Steinhardt can and did take the course.

Course Description

These two 2-credit consecutive semesters, open to all majors, seek to investigate contemporary literary movements in the Greater New York area. We will do close readings and analyses of the novels, short stories, essays, and poems of writers now living in the greater New York area and meet some of them at literary readings at the NYU Bookstore, Book Court, McNally Jackson, the Brooklyn Book Festival, and the 92nd St Y.

Course Activities

Oral presentations, discussion in class and around the city, Blackboard Forums, and attendance at literary readings are all important course activities. We will start class with a 30 minute NYC poetry slam where each student reads a poem aloud of their choice from the anthologies. Then we will spend two hours discussing the book of the week and going over their written close textual analyses on it. When we attend literary readings we will chat before and afterwards if possible. Hard copies of close textual analyses must be handed in to me at literary readings. Friday morning Discussion Board in Blackboard will help

with close textual analysis. October 31, 2011 will be a Literary New York Halloween party at the NYU bookstore. Come in costume. Bring tricks, treats, friends, family, and poems, dramatic monologues, and/or prose passages to read that describe New York and Brooklyn in gorgeous, startling, or unusual language. This will also be a philanthropic event.

Questions for reflection: During the semester, here are some questions to focus your reading and help you choose a thesis for your final paper.

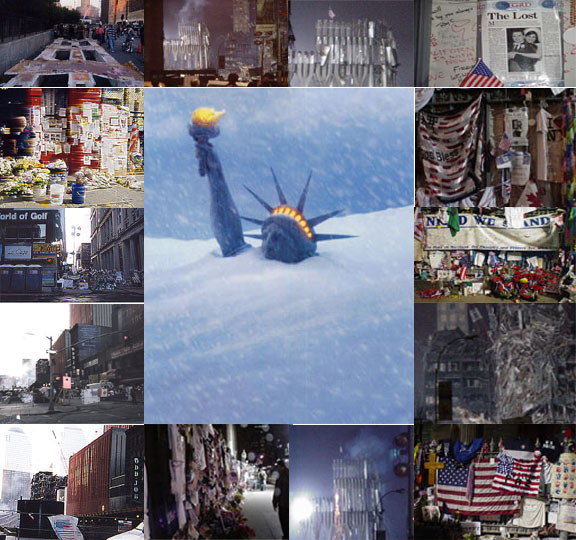

1) How has the representation of September 11 influenced contemporary New York authors and moved readers through specific style, structure, and characterization?

2) How are the sounds and senses of New York represented in New York poetry?

3) What is a great sentence in both the maximal and minimal styles, contrasting writers like Moody and Egan, Hamill and Whitehead, or De Lillo and Safran-Foer?

4) How do the authors connect emotionally to New York? Do they hold a distinctive view of the city?

5) How do narrators and characters respond to their environment?

6) How does the dramatic structure of a given book compare to its narrative style and sequencing?

7) Are syntax, typography or word choices influenced by descriptions of the city?

Course Objectives

To improve skills for close textual analysis

To sharpen and deepen critical thinking

To improve writing skills and oral communication

To learn more about the literature of New York

To meet NYC authors, hear them read, and talk to them about their work

To compare and contrast the styles and structures of different NYC literary works

To discuss the literature with each other in fun, friendly forums

Required Reading

First semester, September 7 –October 31st. LITR 1 DC 6282.001

The following are your TEXTBOOKS but buy them USED at the NYU bookstore!

Falling Man by Don De Lillo

Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran-Foer

The Colossus of New York by Colson Whitehead (short poems)

The Black Veil by Rick Moody

Invisible by Paul Auster (Harlem Redux or Black Orchid Blues by Persia Walker optional)

II. Second semester, November 7 – December 19th. LITR 1 DXC 6282.002

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

The Kid by Sapphire

Thoughts without Cigarettes (Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, optional) by Oscar Hijuelos

Chronic City ( The Ecstasy of Influence optional) by Jonathan Lethem

Forever(Tabloid City optional) by Pete Hamill

Reference Books for both semesters:

Required: Writing New York by Philip Lopate, New York Poems, Literary Brooklyn by Evan Hughes

Optional: How to Read a Poem by Edward Hirsch, Manual by Justin Long-Moton, Reading like a Writer by Francine Prose, and How to Write a Sentence by Stanley Fish

Course Requirements

Because these are short semesters, ALL writing grows into the final 10-20 page paper. Book discussions due by Friday every week in Blackboard; your weekly close textual analysis due every week in class and the poems you choose to read aloud can all be used in the final paper. Individual conferences will be scheduled to discuss this final paper.

1) Weekly Written Close Textual Analysis of chosen passages. After triple-spacing the chosen passage, your analysis should be at least two pages single-spaced. Bring two hard copies to class every Monday. Use my notes from my e-book Carving Your Story to help you write a close textual analysis.

2) Before Friday morning submit an entry into the thread on that week’s book in Blackboard. This is not extra work as it will help with close textual analysis.

3) Bring a poem from Writing New York or New York Poets to read aloud every week that we meet in the classroom for the first semester. Tell us why you chose it and how it relates to your project. This is only required for Semester One to prepare for the New York Word Symphony at the Halloween party. During the second semester, you can work on your My New York essay.

4) Discussion and Participation in weekly classes. You cannot get an A if you miss more than one class. Do not email me if you have to miss class. To be fair to all students, you should not try to get special treatment. The syllabus is detailed enough so that you can keep up. I also have conference time 30 minutes before class as well as at all literary readings and events.

5) Final paper should be around 10 pages and is a guiding question or thesis developed in your Forum using your weekly analyses as evidence and reference.

Semester 1: Final paper due October 31.

Semester II: Final paper due December 19

Blackboard

Besides the syllabus in Blackboard, (please print and bring to class) which is also at https://pages.nyu.edu/keefer/twenty/contnyc.html, we will use the Discussion Board or Forums every Thursday. Use student will read the entries on the weekly thread and that book and post a comment using as many of the following questions as possible to analyze what you are reading.

1) What is a great sentence and how do the parts of the sentence relate to each other to produce what effect?

2) How is tone color, such as onomatopoeia, assonance, consonance, and alliteration, used in fiction?

3) How are metaphors, similes, personification and other figures of speech used?

4) What kind of rhythm do you find in this prose? Please scan it and then analyze it in terms of content.

5) What are the narrative voices and styles of this novel or memoir?

6) How do character motivations fuel dramatic structure?

7) How do character transformations feed the story arc?

8) What is the narrative sequencing and how does this reflect the theme and the style?

9) How does the author juggle with character orchestration and does this help or hurt the theme and dramatic structure?

10) Which kind of imagery--visual, olfactory, gustatory, kinesthetic, aural, or tactile--is most prevalent in this writing and how does this color the content?

11) How does typography such as that used in A Visit from the Goon Squad or Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close or the conventional layout in other books (chapter titles, breakdowns, italics etc) deepen the theme, central dramatic question, and structure?

12) What is the difference between the theme and the central dramatic question and how do they play off each other as the story progresses, regresses, or spins in stasis?

13) How does the dramatic structure differ from Aristotelian or Hollywood plot points and what does this do to the levels and layers of conflict?

14) Since the author is not necessarily the narrator, except in memoir, how is the author's life and voice absent or present in the writing?

15) How is the subtext fabricated by the secrets, shame, and lies of the characters and what does this bedrock due to the dramatic momentum or stasis?

All these style and technique forums should relate in some way to the content of the contemporary New York culture.

Hard Copies for Class

2 copies of your close textual analysis

2 copies of the weekly poem you chose

Course Outline

The following breakdown is subject to changes, based on the availability of writers and book tours.

Semester I: September 12 – October 31

September 8: Thursday at 7 at McNally Jackson. Granta.

September 9: Friday at 7 at Book Court in Brooklyn for a Ten Years Later Retrospective. (optional)

September 12: Introductory lecture and discussion. Setting the scene of 21st Century New York Literature

Meet Evan Hughes of Literary Brooklyn at the Book Court on September 13 at 7. (optional)

September 17: 2-5. Meet Paul Auster et al at Community Bookstore in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Book Fair on September 18: This year’s festival features Jennifer Egan, Colson Whitehead, Pete Hamill, Paul Auster, Siri Hustvedt, Jhumpa Lahiri, Amy Waldman, Jonathan Safran-Foer, Nicole Krauss, Pulitzer Poets, international authors and multi-media and culinary events. The festival is free and runs from 10 to 6 with events at Borough Hall and all over Brooklyn. There is a beautiful earth show in the new park on the waterfront at 7 and then we could walk back across the Brooklyn Bridge as the natural light fades and city lights sparkle. Or some of you could attend the Brooklyn Bash at 8 with Colson Whitehead et al.

September 19: Don De Lillo. Falling Man. (optional Cosmopolis as background)

Pete Hamill at NYU Bookstore on September 24 at 4. (optional) Edward Hirsch is talking about his poetry book at the 92nd St Y this afternoon as well.

September 26: Meet at WTC memorial if we can at 6:30. Discussion of Safran-Foer Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

October 1: Poetry Reading in the Bronx Botanical Gardens at 4. (optional)

October 3: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann.

October 10: On site holiday. Don’t come to the classroom. Forum discussion due Thursday October 13.

October 17: The Black Veil by Rick Moody.

October 18: Poet Charles Simic at the NYU Bookstore. 6:30. (optional)

October 20: Colson Whitehead at McNally Jackson at 7. Meet at 6:20 at Indian restaurant a block west on Spring St if you like. (optional) Get signed copies of Colossus of New York and his new Zone One!

October 24: Invisible by Paul Auster (optional Harlem Redux, Black Orchid Blues by Persia Walker, one of our Halloween guests) Compare thrillers.

October 31: Final due for Section I. Celebrate with a Halloween party at the NYU Bookstore. Final paper is 4 edited CTs, as well as some kind of oral presentation of New York poems, dramatic monologues, and prose passages, in costume or not, with the New York Word Symphony. Guests are Justin Long-Moton, Persia Walker, Todd Anderson, Thomas Fucaloro, Cyd Fulton and class members.

Literary Halloween at the NYU Bookstore. October 31, 2011

COURSE OUTLINE: Semester II: November 7 – December 19.

You don't have to bring poems every week this semester as we will be all over town. Instead, revisit your My New York essay, carry a notebook on it, and develop it as we travel around meeting authors. CTs are still due every week on site preceded by Friday discussions in Blackboard. You must buy tickets to the 92nd St Y immediately to see Egan, Sapphire, and Hijuelos.

New Classroom is LL33, 7 East 12! But we will only be there November 7, November 28, December 12, and December 19. Otherwise we will be at literary readings meeting the authors, usually at the 92nd St Y. We will have at least 60 minutes of class before we meet them at a local cafe so bring 2 hard copies of your CTs for that week.

November 7: Introduction to Section II. To introduce new students to the themes and questions of the course, Alumni from the first semester will summarize and analyze what happened in the first half of the semester and lead discussions. Work on My New York essays as well. Lecture on literary analysis.

November 8: Meet Jonathan Lethem at the Brooklyn Book Court at 7.

November 11: Blackboard discussion of Chronic City.

November 14: Bring 2 copies of CTs of Chronic City. A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan at 92nd St. Jeffrey Eugenides who also won the Pulitzer Prize will talk with Egan. Y on Lexington. Meet at 6:10 at Marmara restaurant, 93rd and Third.

November 17: Blackboard discussion of A Visit from the Goon Squad.

November 19: Poetry Reading in Bronx Botanical Gardens at 3.

November 21: Bring 2 CTs of A Visit from the Goon Squad. Meet at the 86th St. Barnes and Noble café near 6 Subway. Writers on Writers William Carlos Williams at 7. Optional tour of UES. 92nd St Y at 8 on Monday to hear Sapphire, the poet and fiction writer, read from The Kid with Sherman Alexie's War Dances.

November 26: Blackboard discussion of Sapphire.

November 28: Meet in the classroom LL33 7 E 12. Bring 2 copies of compare/contrast of Sapphire, Egan, and Lethem in one document.

November 29: Meet Don DeLillo and Paul Auster at the Barnes and Noble Union Square Granta event at 7. But get there at 5 as it will be full.

November 30: GSAS/CAS Professors poetry reading at the NYU bookstore.

December 1: Edgar Allan Poe performances at NYU Law School. 6-8 pm.

December 1-2: Elizabeth Bishop performances by Gallatin school around campus, afternoon and evening.

December 2: Blackboard discussion of memoir and Hijuelos.

December 3: 2pm. Meet at White Horse Tavern for a Literary Pub Crawl. (optional) This is a 3-hour pub crawl where actors recite poetry by Dylan Thomas, ee cummings et al, and we look at the architecture of favorite haunts and homes of famous authors from the Literary Greenwich Village period.

December 5: Life Without Cigarettes by Oscar Hijuelos at 92nd St Y on Lexington Avenue at 8. Meet at the Chinatown East restaurant at 6:00 on Third Avenue between 92 and 93. Bring 2 copies of CTs of this book.

December 8: Blackboard discussion of Pete Hamill.

December 9: E. L. Doctorow in the Rosenthal Pavilion of the Kimmel Center at 7 pm. First come, first-served.

December 10: Literary tour of Harlem. Meet at Steps Dance Studio at noon, Schomberg Center for Black Culture at 1. We will visit homes of Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Ralph Ellison et al and see Strivers Row from Walker's books, then go to CCNY where Hijuelos and Sapphire studied then up to Inwood to see the places in Hamill's and Lethem's books.

December 12: Bring 2 copies of CTs of Forever by Pete Hamill. Meet in the classroom.

December 19: Meet in the classroom. Bring two copies of your My New York paper to read aloud. My New York should be at least 10 pages and can include creative and critical work about your experience of New York and what you learned from reading our major New York authors. Possible trip to Bar 13 for the poetry slam at 8 or 8:30.

EVALUATION AND GRADING CRITERIA

RUBRIC FOR MAJOR AUTHORS: CONTEMPORARY NEW YORK CCCC 4 times 25 equals 100

Criteria |

Superior work (A) 23-25% |

Exceeds expectations (B) 19-23% |

Meets expectations (C) 14-18 % |

Below Expectations |

Does not meet expectations (F) below 11% |

Control of correct English |

Shows mastery of conventions of English grammar and syntax and writes fluidly with coherence and authority in correct MLA style |

Good control over conventions of English grammar and syntax; wring could be more fluid and coherent, a few proofreading errors |

Inconsistent control of conventions of English grammar and syntax, writing is often choppy, voice lacks power and persuasiveness |

Often lacks control of conventions of English grammar and syntax, voice is weak or inadequate, MLA style is not used |

Unable to handle conventions of English grammar and syntax, no voice is present, no mastery of MLA style |

Connotative |

Shows mastery of the vocabulary and use of figures of speech, tone color, rhythm, rhyme, style, structure, and sequencing and other elements that appeal to the senses and imagination and how this connotative language is connected to content and theme |

Has good insight into connotative language and aesthetic devices but doesn’t always see the deeper implications or connection to content and theme |

Limited understanding of connotative language and aesthetic devices, makes a few connections between form and content but needs to further study |

Minimal understanding of connotative language and aesthetic devices, is unable to connect the literary art to theme, content, or characterization; has minimal feeling for the aesthetic aspects of language |

Has not studied the Lessons on Close Textual analysis and has no understanding of connotative language nor |

Cultural awareness |

Has full insight into the contemporary time period in terms of style and structure as well as characterization and theme and compares and contrasts with sensitivity |

Has good insight into the contemporary time period, but sometimes has blind spots or fallacious assumptions when comparing and contrasting |

Inconsistent insight into the

|

Has poor insight into the contemporary New York literary movements in terms of style and content |

No understanding of the contemporary New York literary movements in terms of style and content |

Control of Claims, Counterclaims and Questions |

Able to name and develop ideas fully, pursuing questions, developing claims, and refuting claims in a fluid, coherent writing style that links the connotative analysis and comparison and contrast to the student’s thesis through example and accurate interpretation |

Controlling idea present and developed. One idea is connected to another, but some of the counterclaims may be missing; the thesis is good but not excellent; some of the questions may not be pursued; a few more examples may be needed |

Controlling idea present, but not fully developed. Inconsistent ability to link ideas together. |

Controlling idea not present and not developed. Weak connection between ideas. |

No controlling idea present. No links between ideas. Little or no development. |

Sample Papers

Comparison/Contrast by Niq Ishaq

Comparison/Contrast by Cathy Abell

My New York by Cyd Fulton

Optional Readings (This is just a bibliography; none of these books are required but may be useful as background, reference, or future reading)

Jazz by Toni Morrison

Selected Poetry by Langston Hughes

Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe

Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote

Writing in Restaurants and Oleanna by David Mamet

Long Day’s Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill

Angels in America by Tony Kushner

Washington Square by Henry James

The Harp-Weaver and other Poems by Edna St. Vincent Milay

Collected Stories of Willa Cather

Terrorist by John Updike

Letters of Allen Ginsberg

Fault Lines by Meena Alexander

The New York Trilogy, Moon Palace, Sunset Park, Brooklyn Follies by Paul Auster

The Keep, Look At Me, Emerald City and other Stories by Jennifer Egan

The History of Love and Great House by Nicole Krauss

What I Loved, The Sorrows of an American, The Shaking Woman, Women without Men by Siri Hustvedt

Motherless Brooklyn, The Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem

Mambo Kings by Oscar Hijuelos

The Intuitionist and Zone One by Colson Whitehead

Fury by Salman Rushdie

Waterfront: A Journey around Manhattan by Phillip Lopate

Netherland by Joseph O'Neill

Empire City by Jackson and Dunbar

Four Fingers of Death, The Ice Storm, Right Livelihoods by Rick Moody

Between Two Rivers by Nicholas Rinaldi

New York the Novel by Edward Rutherfurd

The Emperor's Children by Claire Messud

Metropolis Case by Matthew Gallaway

Overnight, Breakers by Paul Violi

Netherland by Joseph O’Neill

Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon

Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri

Brooklyn by Colm Toibin

Eight White Nights by Andre Aciman

Tree of Codes by Jonathan Safran-Foer

The Big Empty by Norman Mailer

Manahatta by Eric W. Sanderson

Blue Angel by Francine Prose

Wake Up Sir by Jonathan Ames

The Privileges by Jonathan Dee

The Assistant by Bernard Malamud

Reruns by Jonathan Baumbach

Money by Martin Amis

Absurdistan by Gary Steyngart

Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby

The Submission by Amy Waldman

New York poetry anthologies for inspiration and special projects

http://www.poets.org/state.php/varState/NY

Cambridge Companion to the Literature of New York edited by Cyrus Patell and Bryan Waterman

END OF SYLLABUS. See below for links, notes, and other inspiration.

|

Frank O'Hara |

John Ashbery |

|

Muriel Rukeyser |

|

Louise Glück |

|

Billy Collins |

|

June Jordan |

Other New York Poets

McGhee is blessed with many NYC poets on the faculty such as Master Teachers Ruth Danon and April Krassner, Catherine Barnett, Elena Rivera, Michael Coppola, Andy Levy, et al and the late Paul Violi.

Web sites

http://www.fakehead.com

Max Lakner et al run this fabulous Web site about hyper-reality, the "New York-ification" of the mind. Fakehead accepts submissions for critical essays, non-confessional poetry, and genius napkin scribbles! Hard copies are available at Book Court and St. Mark's Books.

Qualifications of Professor Keefer for this course

PhD from NYU, two Masters Degrees in literature, drama, oral interpretation, and media

20 years experience teaching adult students

Creative (a trilogy of novels, especially Un-Clashing Civilizations) and critical publications during this time period—1990-2011

Presentation of paper at the post-9/11 NYC Literature Conference at the University of Westminster, London in 2008

Professor Keefer was chosen as the PhD external advisor for a doctoral Egyptian student at Al Azhar because of this specialty as he is writing his dissertation on about contemporary American literature.

At the 2010 NEMLA conference in Montreal, Professor Keefer followed the contemporary New York and urban pastoral track for American literature. (For global literature, she did French and Middle Eastern tracks.)

Weekly attendance, every Monday night, at NYC literary readings at the 92nd St Y and throughout the greater NYC area

PEN member

Faculty Participant for the Health and Humanities Initiative of Bellevue Literary Press

Co-founder, Media Relations, and Coordinator for Literary Club at McGhee

Currently writing a novel that begins in New York in 2010

Lifetime Commitment to McGhee students

Course Lectures

Sometimes literary communities can oust their founders, or vice versa: “Brooklyn is repulsive with novelists, it’s cancerous with novelists. That can sometimes be too much when you need to also be inside yourself, exploring your own meandering feelings, not dictated by your environment, but dictated instead by what you read that day, or something else.”(Jonathan Lethem) (Come and meet Lethem at Book Court November 8 because he now lives in California.)

In Brooklyn's defense, first-time Fort Greene author Carey Wallace, who recently published The Blind Contessa, said, “The vibrant literary scene in Brooklyn — and the noise and ‘traffic’ it generates — aren’t something I’m likely to take for granted — let alone complain about," adding, "In my experience, a writer’s only weapon is their ability to direct the traffic in their own head. As far as I’m concerned, the level of ‘mental traffic’ here in Brooklyn keeps us in fighting shape. It’s not an edge I’d want to lose."

We will debate the following Franzen claims:

Feel free to disagree with all of the above--I do. (Keefer)

Write out a passage from the book, approximately one page, triple-spaced, numbering every line. The triple spaces are for you to analyze meter, long and short stresses, or note figures of speech, and to really focus on the exact words the author has written. Mark up this passage but do not write your essay in between these spaces. Your analysis comes after the passage in standard MLA format with good sentence structure and paragraph progression. Do not do bullets and bytes. In the age of the Internet, it is easy to get literary analyses and critical theory, so it is important for you to focus on your initmate relationship with the text and what it means to you. As such, I will not be giving examples of the ideal textual analysis. In fact, there is no ideal analysis, because every text is different and you are all different from each other. It's not objective like arithmetic. This lesson will give you guidelines to help you with the vocabulary and structure of analysis, but you must make it your own, edit it, and improve upon it throughout the semester. At this introductory level, pass/fail grades are given because analyses can always get better. I know a PhD candidate who has been analyzing Yeats for the past forty years. Be patient with yourselves, read closely, and focus carefully, but use your imaginations to interpret the text your way.

Analyze the passage for denotative and connotative meaning, relationship to the rest of the text, rhetorical devices, structure, and aesthetics. Even though you are concentrating on a single passage, it is important that you read the entire work to understand its relationship to the whole. First of all you must understand the denotative and connotative meanings of every word in the text. Use your thesaurus and dictionary frequently so that you understand every possible meaning, even when you think you know what is being said. Then analyze sentence structure (simple, complex, compound, compound-complex) and paragraph structure and progression in a novel or short story, dialogue and action in a play, prosody if a poem. Most of your works are novels but you should also know how to analyze poetry.

When you analyze language, place close attention to both diction, or choice of words, (formal, informal, colloquial, concrete, abstract) and rhetorical devices. Even prose passages can be scanned to determine rhythm. It is not enough to identify these devices-- you must relate them to the whole, and evaluate their impact on story, dramatic structure, narrative voice and sequencing, aesthetics, meaning, and character objectives.

This first close reading focuses on the HOW of the text, how the writers created the beauty and meaning from the words they chose arranged as they saw fit. By understanding prosody, style, and structure you can get better breakdown the passage into its components. Then you can ask the WHY questions that connect this form to content. Language is a symbolic and metaphoric art. To be successful, the readers must translate these black lines on the white page into images, feelings, and thoughts in their minds that bring the world to life. It may not be the exact world the writer intended, which is part of the reader-response criticism discussed in the literary theory Lesson.

Does the passage describe a natural or artificial scene and what is the degree of plausibility, suspension of disbelief? How vivid and explicit is the descriptive language? To which senses does it appeal most? Does it describe character as monologue or dialogue, explicit or unconscious? Does it describe an action, develop an argument or an idea connected with the larger world of the fiction? How is the passage sequenced, in other words, what comes before and after, and why? How does this relate to the overall dramatic structure? Is this a passage devoted to exposition, complication, turning point, crisis, climax or resolution? What are the levels of empathy or emotional involvement? Comedic techniques or devices to increase suspense and drama? In what person is the novel told? In a drama, how successfully are the characters orchestrated? How is language used aesthetically to develop theme and how his theme related to the central dramatic question and the protagonist's objectives? In this global literature course, how do style and structure reflect the taste of the indigenous culture? How does this passage compare with another one on the same content, but from a different culture? For whom is the story written? How does the narrative voice relate to audience?

After thinking about all of the above, let us go into detail on the various sections. Part I Lesson I focuses on Form, while Part II focuses on content.

FORM

Meter in poetry or grammar, sentence length, paragraph progression in prose

Rhythm in stressed and unstressed syllables

Rhyme where applicable

Tone Color including alliteration, assonance, consonance and onomatopoeia

Figures of Speech including metaphors, similes, personification, analogy

Read aloud your triple-spaced passage and note the sentence length, paragraph progression or prosody in poetry. How long or short are the lines, sentences, and paragraphs? What effect does this have? Always relate form to the overall meaning. In translated works, you can still analyze the length of lines, sentences and paragraphs but not the exact meter, rhythm or tone color. These are reserved for works written in English.

Meter is analyzed in terms of metric feet--iamb,u_ trochee,_u anapest, uu_dactyllic, _uu, spondee, __pyrrhic,uu. Most British poetry is written in iambic pentameter. A spondee has a finality about it while a pyrrhic is light, an anapest is a waltz rhythm, and a trochee makes you stop and think backwards.

Rhymes can come at the end of the line and a rhyme scheme can look like this A B A B C D E C D E FF, refering to the end of the line, but rhymes can also be internal. In Part III of my trilogy I have the Electroweak Force narrator talk in rhymes because it mimics the electrons. What do rhymes do to the meaning of the piece?

Words are letters taking up space on a page that when read aloud form a pattern in time. What is the overall affect of this pattern related to the meaning of the book?

Tone color relates to the sound of the words, like movement quality amplifies dance, resonance music, and color painting. Alliteration is the repetition of the first sound like "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers." Consonance is the repetition of consonants like "Sister Suzie sells seashells down by the seashore." Assonance is the repetition of vowels like "How now, brown cow." Onomatopoeia occurs when the tone color mimics the sound of the thing described, such as "babbling brook." There are many categories of tone color, but see how the style determines how you feel about the characters and their thoughts and actions and how you experience the setting.

Figures of Speech refer to words that are used to connote other things or feelings than what is being literally described. A simile uses like or as if, such as, "her eyes are like seashells," while a metaphor says something is something it is not, such as "her eyes are seashells." Personification is the attribution of human characteristics to non-human entities such as the narrators in My Name is Red or Part II of my trilogy. Obviously, trees, dogs, cats, the Statue of Liberty, the Sphinx etc cannot speak English but we personify them to give depth and breadth to a story.

Even in translation you can evaluate figures of speech. What do they do to the experience of the passage? Some Native American writers prefer literal words and meanings because the sky and the sand are good enough, while writers like Virginia Woolf make put diamonds on waves, and describe nature in terms of human beauty. What do the figures of speech reveal about the narrators, characters and their worlds?

Rhetorical Devices

Using selections from All Quiet on the Western Front as examples, please review the following to help you with close textual analysis:

Humor, with metaphor: "My arms have grown wings and I'm almost afraid of going up into the sky, as though I held a couple of captive balloons in my fists."

Personification: "The wind plays with our hair; it plays with our words and thoughts."

"Over us Chance hovers."

Euphemism: "At the same time he ventilates his backside." "All at once he remembers his school days and finishes hastily:'he wants to leave the room sister.'"

Imagery: "To no man does the earth mean so much as to the soldier. When he presses himself down upon her long and powerfully, when he buries his face and his limbs deep in her from the fear of death by shell-fire, then she is his only friend, his brother, his mother; he stifles his terror and his cries in her silence and her security; she shelters him and releases him for ten seconds to live, to run, ten seconds of life; receives him again and often forever." (and personification) "The front is a cage in which we must await fearfully whatever may happen."

Repetition: "Earth!-Earth!-Earth!"

Antithesis: "A man dreams of a miracle and wakes up to loaves of bread."

Parallel Construction: "My feet begin to move forward in my boots, I go quicker, I run."

Simile: "He had collapsed like a rotten tree."

Metaphor: "Immediately a second [searchlight] is behind him, a black insect is caught between them and tries to escape--the airman.]

Liturgical prose: "Our being, almost utterly carried away by the fury of the storm, streams back through our hands from thee, and we, thy redeemed ones, bury ourselves in thee, and through the long minutes in a mute agony of hope bite into thee with our lips!"

Apostrophe: "Ah! Mother, Mother! You still think I am a child--why can I not put my head in your lap and weep?"

Allusion: "The guns and the wagons float past the dim background of the moonlit landscape, the riders in the steel helmets resemble knights of a forgotten time; it is strangely beautiful and arresting."

Hyperbole: "They are more to me than life, these voices, they are more than motherliness and more than fear; they are the strongest, most comforting things there are anywhere: they are the voices of my comrades."

Rhetorical question: "If one wants to appraise it, it is at once heroic and banal--but who wants to do that?"

Aphorism: "...terror can be endured so long as a man simply ducks--but it kills, if a man thinks about it."

Symbolism: "I pass over the bridge, I look right and left; the water is as full of weeds as ever."

Foreshadowing: "On the landing I stumble over my pack, which lies there already made up because I have to leave early in the morning."

Doggerel: "Give 'em all the same grub and all the same pay."

Short Utterances: "Life is short." (Analyse for rhythm and effect.)

Cause and Effect: "They have taken us farther back than usual to a field depot so that we can be re-organized."

Irony: "...a high double wall of yellow, unpolished, brand-new coffins. They still smell of resin, and piine, and the forest."

Appositive: "Thus momentarily we have the two things a soldier needs for contentment: good food and rest."

Caesura: "It is all a matter of habit--even the front-line."

Onomatopoeia: "The man gurgles."

Alliteration: "The satisfaction of months shines in his dull pig's eyes as he spits out: 'Dirty hound'"

Euphony: "Now red points glow in every face. They comfort me: it looks as though there were little windows in dark village cottages saying that behind them are rooms full of peace."

Cacophony: "The storm lashes us, out of the confusion of grey and yellow the hail of splinters whips forth the child-like cries of the wounded, and in the night shattered life groans painfully into silence."

Slang: "And now get on with it, you old blubber-sticker, and don't you miscount either." "That cooked his goose."

Rhetorical devices also include the syllogisms, logical fallacies etc explained at www.nyu.edu/classes/keefer/brain/argue.html.

Critics analyze in reverse of how many writers create, except poets, who often start with language and word games.

FORM

Meter in poetry or grammar, sentence length, paragraph progression in prose

Rhythm in stressed and unstressed syllables

Rhyme where applicable

Tone Color including alliteration, assonance, consonance and onomatopoeia

Figures of Speech including metaphors, similes, personification, analogy

Story is the simple chronology of events, specific as to time, person and place but often oblivious of dramatic structure.

Dramatic structure is the orchestration of conflict in the story, exaggerated or edited to produce an exciting fight (mental, physical or spiritual) between protagonist(s) and antagonists. In the classical model, this conflict is related to a central dramatic question, objectives, obstacles and plot points characterized by catalyst, commitment, confrontation, chaos/low point, crisis, climax and conclusion. We will also study the Ordinary World/Special World Journey created by Joseph Campbell. Some modernist and postmodernist writers create their own dramatic structure or improvise and ignore it.

Narrative structure is the way the events are sequenced in time and space from the point of view of the narrator in a book and/or camera in a film in such a way that a style is created that expounds the theme, or the way the author feels about the material. In novels and short stories, the narrator or narrators tell the tale in the first or third person, singular and/or plural, and rarely in the second person. In film the narrator can be a real person who occasionally narrates over the action, or simply the POV of the camera.

For example, the CDQ in Pulp Fiction may be “How will the crime unfold among Vince, Jules, Butch etc., but the two themes are “Crime works if you can keep it a secret” within the chronology of events, or “It is possible to get out of crime with a spiritual transformation” based on the focus on Jules' epiphany at the conclusion in the way it is filmed. The story of Pulp Fiction is a mundane one of murder and double-dealing throughout three days with drug dealers; but the narrative structure of the stop action, rewind and fast-forward of a VCR turns the story into a dramatic structure with multiple protagonists where a character with little screen time has the character transformation that restructures the story into both an Aristotelian structure with three crises/climaxes, or a monomyth where Jules emerges from the special world to have a transformation. Don't worry if you don't understand all this right away, as it is covered thoroughly the course.

In Romeo and Juliet, the story is about these young lovers from the warring Capulet and Montague families; the CDQ is "Will they get married and live happily ever after or not?" and the theme is "True love never runs smoothly," refering to Shakespeare's attitude toward the material, so that the sequencing of events lead to the tragic, untimely deaths of the lovers.

To survive we need to drink water and eat some kind of food, even if it is injected as glucose. But do we need stories to survive? Every time we recount an action or listen to what happened to someone, we are engaged in storytelling. Every time we plan or hope that something will happen to us, we are engaged in the same kind of dramatic structure as our protagonist. If there were no stories, we would live in the present, erasing our footprints as if caught in a heavy snowstorm. We would not be able to learn lessons from the past, remember what happened to us, or anticipate what might happen. If we continued to eat and drink, we would exist, but we might not know where to find our food or how to make the money to buy it, how to prepare, clean and cook it avoiding disease, and how to balance our needs nutritionally; therefore, we might literally die of starvation and dehydration.

To find our food, we must kill an animal, fish, cut a plant or tree, gather nuts and berries, dig up a root vegetable, or just go to the store and buy food.

However, we earn our money by metaphorically killing animals, cutting life, planting, gathering, digging, or just being at the job and doing what we are told. We can also find stories in all these different ways.

Not all stories are told for entertainment: every discipline has its narrative so that doctors learn from case studies, lawyers from trials, and schoolchildren from educational narratives. These real life stories may not differ that much from our fictive creations, as in courtroom dramas, detective thrillers, or historical period pieces. Creating your own story is a form of empowerment, giving you a feel for some of the omnipotence of the Creator, so when the story lands in your lap, do you still see its potential?

A story is not the same as a dramatic structure that we manipulate, although some stories seem as if they were created by a top dramatist. A story is simply what happens to specific people or personified objects in a specific time and place. There may be 36 dramatic situations but there are millions of stories because people are unique.

When we pick a story from life, we take it out of its world, an excision that will determine the level of reality, be it documentary, naturalistic, realistic, romantic, fantasy, sci fi, or surreal. As you write, the reality may change, but remember the world that originally gave birth to your story.

Examine the world in which the story is created:

a) American naturalistic contemporary,

b) global indigenous,

c) historical or period,

d) sci fi,

e) aesthetic-- surrealist, impressionist, i.e. blue lens over the set as in Blue Velvet,

f) musical,

g) animation,

h) cyberspace,

i) extreme outdoor set,

j) fantasy elements but not complete sci fi. Superman Spiderman etc.

How does the protagonist's objective connect to the his or her world?

75 % of my students have this motive-- to establish a career, or get a good grade, or get into a good school. This won't work for a feature film unless it leads to higher stakes, such as a crime, insipid politics, undying love, or the ability to sacrifice for an ideal. Otherwise people won't identify with this. Or you go into a supernatural realm and you really get supernatural powers. But these mundane, petty motives don't work.

Examine the subject matter or area where main motivations occur, such as:

a) love, including sex, obsession, self-love, family love, and companionship--brotherhood, sisterhood. includes hate

b) money for greed or survival, not just the mundane weekly salary unless the character is starving

c) fame-- adulation of everyone

d) power-- governmental politics but all power plays with high stakes

e) ideals-- religious, or freedom, honesty, even magical or superhuman power -- as long as character is willing to sacrifice for them

f) crime-- anything that is against the law-- theft, murder, rape, arson, conspiracy, embezzlement-- from the point of view of the victim, (thriller) the lawyers (courtroom), detective, perpetrators (gangster) etc. Western can be in crime or war or both.

g) war-- legitimate and illegitimate wars-- between real or fictional characters with all the devastation, honor, patriotism, horror that this implies.

h) adventure-- i.e. anything for fun, battling nature for outdoor sports, or teams for sports, concerts etc. The goal is to have fun. The mode is action.

i) birth-- the desire to give birth, if you can't, either literally to a baby or to an invention or idea, or coming of age-- to give birth to an older, more mature self as in BIG.

j) death-- fighting addictions, fighting diseases, shamans, doctors, patients etc.

k) disaster--natural or manmade--where fighting the disaster is the focus more than a war or a plague which would be in other categories.

In Waiting for Godot, it is about the hope for or absence of God, hope, higher power; it isn't really about waiting for godot. Exit the King is about fighting death with an existential appreciation of life. Motivations need not be conscious or wilful.

Sometimes you must spend a long time researching the world of your story. To write my trilogy, How to Survive as an Adjunct Professor by Wrestling, I had to go over and over the events in New York after September 11, travel to Egypt, Turkey, Morocco, and Paris, and study cosmology, particle physics, the Muslim religion, and American foreign policy. For my Huguenot St. novel/screenplay, I have had to research geology, Native American tribes and culture, Huguenot religious persecution, small town politics, seventeenth century history of the Hudson Valley and Shawangunks, and various immigrant habits and cultures.

Imagine what the writers had to do to find and create their stories.

Dramatic Structure |

Dramatic Structure is the organization of conflict between characters in their world. Cut, carve and cook it, simmer, sauté, bake, broil, boil, or serve your meat raw and bleeding. Stay here for the mountain versus the circle, but for Boolean layers, caravan tales, and other paradigms influenced by twentieth century physics, and how world cultures experience time and space analyze each work separtely.

Steam-the Aristotelian pressure cooker.When you steam food, you preserve the texture and vitamins, but you make it really hot. If you steam too long, it will wilt or get soggy; if you don't steam enough, part of it remains cold.

Coffee benefits from the steaming process and sometimes makes us think more sharply.

Drama began from our love and need for imitation, harmony and rhythm. Tragedy is an imitation of characters of noble birth and comedy of inferior types whose flaws are so exaggerated and real that we can laugh at them. Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete and of a certain magnitude, in language embellished with each kind of ornament, through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of the audience's emotions.Pity is aroused by unmerited misfortune; fear by the misfortune of a man like ourselves. Every tragedy must have six parts: Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Song. Aristotle feels plot is more important than character because the most beautiful colors, laid on confusedly, will not give as much pleasure as the chalk outline of a portrait. Do you agree? Spectacle is the least important. Diction involves the delivery of words that are either current, or strange, or metaphorical, or ornamental, or newly-coined, or lengthened, or contracted, or altered. The perfection of style is to be clear without being mean or too literal, vulgar, simplistic etc.

Aristotle disliked episodic drama: for tragedy to be worthwhile it had to be a well constructed story with a beginning, middle and end that proceeded from action to counteraction by necessity and probability. There is a strong connection between what he wanted from drama and what he wanted from rhetoric, although the purpose of tragedy is to purge the emotions. Tragedy must be simpler and more credible than comedy if it is to move us to tears rather than laugher. A simple plot is one which takes place without reversal or recognition. A complex plot has reversals and recognitions which should arise from the internal structure. The best form of recognition is coincident with reversal, as in OEDIPUS. Characters must be chosen in such a way that their actions raise the stakes of the drama. It's better to have family members kill each other than an enemy kill an enemy because then you can construct scenes that have the elements of betrayal, jealousy, fear, love etc. as well as anger. The DEUS EX MACHINA must only be employed for events external to the drama; the crisis/climax should arise of necessity from the inciting incident, just the way it's supposed to do in Hollywood screenplays. Every tragedy falls into two parts: complication and unravelling. Complication is every action that moves to the turning-point from good to bad fortune and unravelling is that which extends from the beginning of the change to the end.

An epic structure differs from a tragedy because it has a multiplicity of plots. Epic structure is similar to what we call narrative structure. However as poetry (Homer) it was usually written in the heroic measure. Alexander Pope satirized this form in his mock epic poem THE RAPE OF THE LOCK in the eighteenth century. Epic tales can be longer, more complicated, more irrational and fantastical because they are not confined to the stage.

In Western drama the most important thing is a hero who badly wants something he can't get; in world mythology, it is the call to adventure to undertake a journey, implying that there are archetypal forces even stronger than the hero's objective. The first is a paradigm of time, heightened by compressing events in space into a limited time span; while the second is a paradigm of space that takes the hero away from the Ordinary World to transform enough in the Special World so he can bring back an elixir to community. Return, resurrection, rescue, archetypes, threshold struggle are some of the terms pitted against plot points, throughlines, premises, reversals, crisis/climax/denouement. While high concept screenplays involve the community and transformative dramas develop character transformation, in the Campbell paradigm, the hero's transformation is a resurrection that brings the community full circle. Campbell's work is motivated by his spiritual search and his recording of stories that transcend the hero's objective to connect to a more universal truth. Many Western stories stay with the self, its foibles, flaws, frustrations, and final triumph in getting what it wants.

The French dramatist, Georges Polti, categorized 36 dramatic situations, that presumably encompass all the major conflicts between characters in drama. If you are basing your story on real life, and want to raise the stakes, you can use one or more of these situations to cook your characters.

Supplication

Crime Pursued by Vengeance

Vengeance Taken for Kindred upon Kindred

Pursuit

Disaster

Falling Prey to Cruelty or Misfortune

Revolt

Daring Enterprise

Abduction

The Enigma

Obtaining

Enmity of Kinsmen

Rivalry of Kinsmen

Murderous Adultery

Madness

Fatal Imprudence

Involuntary Crimes of Love

Slaying of a Kinsman Unrecognized

Self-sacrificing for an Ideal

Self-sacrifice for Kindred

All Sacrificed for a Passion

Necessity of Sacrificing Loved Ones

Rivalry of Superior and Inferior

Adultery

Crimes of Love

Discovery of the Dishonor of a Loved One

Obstacles to Love

An Enemy Loved

Ambition

Conflict with a God

Mistaken Jealousy

Erroneous Judgment

Remorse

Recovery of a Lost One

Loss of Loved Ones

Think of what steam does. It cooks the ingredients while maintaining their integrity. When you steam fish and vegetables, you eat fish and vegetables, not a casserole.

Fried food is a fast way to cook, one that allows you to see what you are doing, and to make fattening food crispy.

Fried food is a fast way to cook, one that allows you to see what you are doing, and to make fattening food crispy.  Bread is usually toasted to give it a crispy flavor, and then plastered with butter and jam, while indigenous cultures generally bake their bread. Pizza can be cooked in a microwave oven, which shortens the cooking time with infra-red waves. Americans don't want to wait too long for the action to begin. Laborous expositions bore them. Americans like to put fruits and vegetables into the blender, or make homogenized milk.

Bread is usually toasted to give it a crispy flavor, and then plastered with butter and jam, while indigenous cultures generally bake their bread. Pizza can be cooked in a microwave oven, which shortens the cooking time with infra-red waves. Americans don't want to wait too long for the action to begin. Laborous expositions bore them. Americans like to put fruits and vegetables into the blender, or make homogenized milk. For a culture that is made up of immigrants, Americans tend to homogenize their stories.

For a culture that is made up of immigrants, Americans tend to homogenize their stories.

Or dice vegetables so they will have a uniform appearance. They like extreme temperature changes, freezing milk and cream into ice cream.

Or dice vegetables so they will have a uniform appearance. They like extreme temperature changes, freezing milk and cream into ice cream.

Many Americans fry their veggies as well as their carbs and protein, making everything as fattening as possible. Yet, in one sense, they like their dramas lean and mean: a theme, a task, a team, a deadline, a competition, a consequence-- you're fired--but that can also be influenced by sequencing and plot complexity.

Many Americans fry their veggies as well as their carbs and protein, making everything as fattening as possible. Yet, in one sense, they like their dramas lean and mean: a theme, a task, a team, a deadline, a competition, a consequence-- you're fired--but that can also be influenced by sequencing and plot complexity.

Dramatic structure, how the conflict unfolds, is not the same as narrative structure, the sequence of events in time and space colored by the POV of the narrator. Dramatic structure is the conflict between protagonist and antagonists as they fight for their through-lines in response to the Central Dramatic Question, a visual paradigm similar to falling off a cliff from catalyst to commitment to confrontation to cataclysm to chaos, crisis, climax and conclusion, timed by plot points. Emotion is consummated in a catharsis.

Americans still find Aristotle useful now for his catharsis and definition of unities of space, time and action and priorities of plot, character, thought, diction, song, spectacle. Shakespeare is good for the gap between expectations and result, colored by the character's dilemma and necessity to choose, a sequence of choices, which reveals deep character. While Americans can't compete with Shakespeare's language, nor do they want to, they have the same epic sense of crisis and climax and its effect on the community. However, they tend to prefer transformational drama to a tragedy where the hero dies. The hero is often a commoner who makes good rather than an aristocrat who falls, reinforcing the democratic social system of American culture.

While the plot points are a paradigm mainly of time, the monomyth is a paradigm of space. The circular journey from ordinary to special world and back and the stages of this journey from call to adventure, to crossing the threshold, approaching the inmost cave, returning resurrected and getting or giving the elixir are similar to plot points except that the spatial aspects represent a circle rather than falling off a cliff, thereby making the set-up and conclusion a bit longer.

Just like argumentation, drama deals with controversy, conflict and conversion in a search for truth except that logical fallacies are glorified to heighten the flaws of the tragic or comic characters. Drama must combust space and time so deadlines, planting and payoff are necessary to heighten surprise and mystery, while irony can enhance suspense and make the audience feel smart. No matter how intricate and discipline the dramatic structure, if the emotions of pity, fear, laughter or lust are not elicited in the audience, then the structure will be more like a legal case than a drama that requires catharsis to transcend the paradigms, just as wonder must transcend prosody in poetry.

World of Time: Plot Points and the Central Dramatic Question- Keefer's C's: Catalyst, Commitment, Confrontation, Chaos, Crisis, Climax, Conclusion

World of Space: Campbell Paradigm, Ordinary and Special Worlds, Bore-dinary and Extraordinary, Call to Adventure, Crossing Thresholds, Meeting with the Mentor, Approach the Inmost Cave, Reward, Resurrection, Elixir

Narrative Voice and Sequencing |

Point of View

What are the differences and similarities between narrative voice in fiction and sequencing in screenwriting? The camera decides who it likes and dislikes depending on actors but does the screenwriter control any of this?

In fiction, a story can be told in the first person, rarely the second person but it happens in some chapters of Soul Mountain by Gao Xi Jiang, third person limited, over the eyes of the main character, or third person omniscient, mimicking God, so to speak. Western readers are used to having one narrator for an entire work and often confuse the author with the narrator, while other cultures, particularly Islamic and Arabic ones, feel comfortable with multiple narrators, whose combined visions, present a rich tapestry of story. American writers often think their narrators are "objective," like scientists, allowing the story to speak for itself, but every time a story is told, there is always a point of view, even if it takes a while to decipher it.

Most of the innovative structure in timespace center on theme more than CDQ. I have explored everything but interactivity, chance and game theory. Most of the recommendations in this book assume that the writer is making choices and designing paradigms. But as with music and choreography, it is also possible to design art by the throw of the dice, so to speak, or games that engage interaction between reader and writer. These techniques surprise the writer as much as the reader, and are good ways to overcome writer's block.

Photo Credit: Michaelsgatling

Nonlinear narrative has existed throughout history but has often been considered defective or inferior to linear narrative. As far back as classical Greece, critics said that Homer's Odyssey has fewer narrative "defects" than the Iliad because the protagonist is always present, and there are fewer loose ends. Even in the twentieth century readers and viewers have complained when a story is difficult to follow or when it it not resolved nicely. With Pulp Fiction, Quentin Tarantino allowed us to follow three stories that stopped, started, reversed and replayed themselves as easily as a VCR. With the advent of hyperfiction and hyperdrama, the timespace structures are infinite and also relative to the surfer who chooses to enter, leave, interact or even follow her own narrative. Just as Aristotelian dramaturgy reflected that culture's views of time and space, our nonlinear narrative could reflect the discoveries of quantum mechanics and cosmology, using space as a microcosm or macrocosm, time that goes back to the future or winds around itself and timespace that unites the two in Einstein's curved spacetime or Stephen Hawking's black holes. The possibilities for nonlinear narrative are endless.

If you stay too long eating this pesto pasta, you won't be able to eat anything else!

If you stay too long eating this pesto pasta, you won't be able to eat anything else!

TIME and REALITY

The oral storyteller weaves his yarn about events that happened in the past in front of an audience, enchanting them with elements of fantasy injected into the people and places with which they are familiar, as in Arabian Nights.

The play takes place in the present even though the characters may talk about the past or future. Novels do all kinds of things with time-think of the complexity of French grammar. There is a difference between the past imperfect and the past simple, the repetition of a habit or an event worth noting. Some novelists write in the present, the past imperfect, the past simple, the conditional or subjunctive in lyric modes.

Television adheres to a meticulous, repetitive schedule of present tense narrative. Film uses present tense with flashback narrative and while it plays out in the present, can rewind or fast forward the story as in experimental films. Both TV and film can use recursive, flashback, tandem or tandem competitive as well as linear narrative. The Internet destroys time-it doesn't matter. The user enjoys or creates the story any time she wants.

For example, Alan Lightman's Einstein's Dreams describes so many ways of living time as if it were one day, going backwards, rushing to Apocalypse, turned into space, or torn between biological and mechanical time.

The smaller the space of the medium, the wider the world of it story-books and computers.

Some desserts look better wrapped, or from a distance. A close-up can make something unappetizing at times, a bit like multi-colored vomit..

If you begin with seafood salad, end with fruit salad.

If you begin with seafood salad, end with fruit salad. Varying the scene order

Lyrical versus Percussive

While dramatic structure relates to central dramatic question, narrative structure relates to theme, the author's attitude towards the material. Narrative structure is described by the voice of the narrator-omniscient, limited, first or third person, non-human, personified or human, distance from the story; the sequence of events in time-linear, recursive or other kinds of flashback, superimposed time or tandem competitive, past imperfect or repetition, out of time in some kinds of expository, lyrical or descriptive writing which may include the emotional subjunctive, conditional or future time expressed in the possibilities of branching narratives and indeterminate endings; and a spatial existence that can be real, imaginary, in the head, superimposed space or disembodied.

What are the unique qualities of print, oral communication, internet/small screen, or movies/big screen that create certain kinds of narrative and dramatic structures? Dramatic structures are the same in all media but narrative structures differ. The Internet is most conducive to branching narratives, tandem competitive time and superimposed space. How do written and oral communication differ? Written communication lends itself to the invisible, omniscient narrator but oral communication insists on the real character of the narrator as in Arabian Nights. Film has glorified the flashback and recursive narrative but branching narratives with indeterminate future are not popular. Run Lola Run is more of a rewind of three stories from beginning to end, rather than a future oriented piece. Film can speed up or slow down but it lives in the immediate present even when flashing back. Stage plays

RECURSIVE: The present is relatively static and the past is used to solve a problem in the present, even if that is to recapture lost time as in Proust, or to stop the plague in Ancient Greece in Oedipus Rex. While the climax of the play occurs when Oedipus plucks out his eyes, the present action up until then has been mainly conversation about dramatic events in the past. When the past is plucked, it is not replayed in a realistic, linear fashion, but filtered through the lens of the present. At the end the digs into the past cause the present to change somewhat. This is often told in first person or through the eyes of a main character. Flashback films and written memoirs, static plays like Oedipus are its forms. How do these forms differ and how do they translate into each other? Recursive is the basis of psychoanalysis where patient and psychiatrist sit in a static present using events in the past to trigger feelings to be catharsized and analyzed in order to solve problems for better action in the future. Oedipus Rex only won second prize in the playwriting competition in Ancient Greece, so some feel this kind of storytelling isn't dramatic enough. This is the basis of reflection, of the thinking we do in memoirs or at the end of the day. But it doesn't work well with multiple narrators or a huge sociological vision or a lot of action. It is for sensory recall, problem solving.

Thwarted dream, case history, life changing event. Ivan Ilyich. Rewind.

TANDEM COMPETITIVE: Stories can be in tandem without competing-sharing the same space or the same time or the same characters with some different factor. In my novel, similar characters appear in different space. It seems as if they are in the same time because they occupy the same novel, but one is in the active, impressionistic, dreamlike present and one the past imperfect, one in the eternal present of dreams and one in a specific period in society and history. They compete when they rival each other for truth from the Reader's POV. There must be a reason why stories are told in tandem. In real life, two versions of the same story are constantly competing in our minds, a phenomenon which reaches its extreme state in bipolar illness where the same state of events can be interpreted as depressing or uplifting, depending on the mood, or actions are constructed to reap those same results, depending on the mood. In other words, something exists before the story because the story is simply how specific people engage in certain events in a specific time and place. Therefore, their objectives, moods, abilities and proclivities as well as social conditions are set before the story occurs. Hence different moods and objectives can actually create somewhat different stories. We sometimes see scenes on split screen or split stage or alternating chapters of narrators in a novel. This narrative style is particularly disturbing as we don't know what kind of truth to accept and our mood is constantly jarred by the constant switches. Yet this is exactly what happens in psychosis.

LINEAR: Linear is the most common kind of storytelling in which a beginning, middle and end follows similar linearity in time and space. However, in dreams, linear storytelling does not necessarily have a cause-effect as is commonly understood. In Hollywood screenplays, script doctors are brought in to make sure there is a causal relationship to the scenes. Usually linear storytelling is told by one narrator, whether first, third or the camera, but in pass the ball linear narrative, multiple narrators carry the same story in sequence, the way storytellers passed tales through the desert from oasis to oasis through different caravans. They tried hard to be true to the story, but each storyteller obviously colored the tale based on his perceptions and values. In my second novel I chose 18 nonhuman narrators or human extensions, as McLuhan would say, to carry the story. This is a technique still used today by writers like Naguib Mahfouz, Yusuf al Qa'id in War in the Land of Egypt and Orhan Pamuk in My Name is Red. You can have multiple narrators without a linear story as in Akhenaten and some of Faulkner's work, but pass the ball linear is like the game broken telephone where narrators try to pace their addition to the story embedded in sequence within its entire history. This gives tremendous importance to the story but protects it from the fallacies of omniscient narrators like those of Tolstoy. Pass the ball linear doesn't lend itself that well to film although it is possible it could be done-something as disciplined as War in the Land of Egypt might work well. My second novel would be hard to film and keep all those narrators. Some things are too difficult to visualize in this narrative. Films and plays take place in a linear fashion but they can refer to events that occur out of sequence in time.

CONGLOMERATE:It seems that in conglomerate narrative, there must be an active throughline in the present that covers winter to winter -one year which is the surface of the rock. Then the layers are the back stories. How does this differ from recursive narrative? Recursive features the past to solve a problem in the present like Oedipus Rex; while conglomerate has a hard active linear present that covers layers of secrets, lies, and history in the past. Conglomerate is neither tandem nor competitive, nor does it deal with the future. The past is not imperfect past but singular events that influence the present. Is conglomerate the right word? The idea is that there is a superficial story with deeper stories underneath, some of which may be too disgusting, disappointing, depressing or disarming for the Reader or Viewer to stomach. For example, soap operas skim the surface of narrative, idealizing characters and romanticizing situations by avoiding depressing details. How many people lie dying with perfect hair and make-up? In a hypertext story there can be the top layer of narrative for everyone, then layers underneath which symbolize gossip, pettiness, uncomfortable facts, and finally those things that are usually censored. This would be one way to deal with Internet censorship. This is different from the usual hypertext story of branching narratives where different future outcomes are envisioned.

Repetitive structures aren't the same as descriptive films. Groundhog Day and Run Lola Run repeat. There are some changes with the different versions.

Parallel structures like The Hours are not sub-plots. The danger here is to be choppy if the sequencing isn't right and there aren't enough similarities or differences between the stories. It is like comparison and contrast in literary criticism. Choppy, flowing, choppy, flowing. But if the narrators argue, if the stories bleed into each other for a reason, it gives the whole script more depth. The Matrix has a number of parallel structures.

Instead of repetition, it might be good to spiral the action so that when characters revisit the scene they attack the problem in a different way. Sometimes the event is seen in flashback. The Unraveling-mystery structure is used with whodunits. The skill involves laying clues throughout the film and then learning the truth in the third act.

In Memento the whole film is a flashback so that it is a reverse structure. The trick is to keep the audience asking a central dramatic question. There must always be a puzzle for the audience to solve. In a circular structure there must still be linear parts. Pulp fiction has a looping structure of beginning-end-middle and more.

Food Pyramid and Character Priorities

Food Pyramid and Character Priorities

By comparing characters to food, we determine how they were found, gathered, or killed from the story, how they will be cooked or prepared in the dramatic structure, how they will be sequenced in time and space or displayed on the dinner table, how they will be eaten, digested, eliminated, and metabolized by the audience or reader. So characters as food relate directly to story structure, genre, and audience. But there are other ways of comparing them.

Objects, Musical Instruments, Animals: Act, Hear and Feel

Food analogies aren't the only ways to create, develop, and orchestrate your characters. By comparing them to household appliances, you get a clear idea of how they act in a situation. A scissor personality is different from a vacuum cleaner, a broom, a washing machine, or a toilet bowl cleaner. Once you see how your characters clean up you may be better able to predict their actions in a scene.

Not everyone speaks the same way. Resonance, pitch, timbre, phrasing and vocabulary distinguish each character so a useful exercise is to assign a musical instrument to each character's voice. A melodious harp plays differently on our ears and psyches than a relentless drum, a schreechy violin, an ethereal flute, a banging piano, a twanging guitar,or a new age synthesizer. Every time you create dialogue, hear the sounds of these distinct instruments and let your characters respond accordingly.

In drama, we want our characters to feel instinctively and act with power.

Therefore, if you assign an animal to each character, you will know how they fight, eat, have sex, and escape. A snake curls up lasciviously on the rock in the sun but will stand up, hiss, and bite if attacked; a mosquito is almost invisible until it delivers its itchy bite; a fish swims fluidly, seeking food everywhere, even on the end of a lethal hook; the gentle, slow-moving elephant can crush life with a single ponderous step; the gazelle is beautiful to look at, but if you approach, it will run away with lightning speed. The lizard blends into its environment. Your pet cat can be dressed up for Halloween. Archetypes are classic character types such as the Shadow, the Hero, the Shapeshifter, the Mentor, whose essence is related to the role they play in the dramatic journey.

Stereotypes are contemporary character types flattened and exaggerated to fit a socially identifiable role. They work best in satire, slapstick, or to provide comic relief in tragedy. If the hero of your transformational drama is a stereotype, you are in trouble.

Three-Dimensional Characters

Height, width and volume? This is a crazy nomenclature but what it means is that characters have dimensions and depth; they break stereotypes, they often act unpredictably, they have many sides to their personality, they have secrets that they hide or lie about, and they change as the story unfolds. A main character may have a kaleidoscopic personality, sounding like a violin in one scene, or a harp in the next, acting like scissors with a girlfriend, but a vacuum cleaner with his professor.

Character Profiles

Age

Looks

How they Change

Wardrobe

Body language and mannerisms

How they talk-sound of their voice

Biology, aches and pains

Musical instrument/Animal/Household appliance

Biography-where lived, degrees, jobs

Daily schedule

Exact behavior at work or school

Objectives

Fantasies

Dreams and Nightmares

Life attitude: Incurable romantic

Major delusion

Major secret

How they lie

Major embarrassment

What they want from the other characters

Whom do they love the most, hate the most?

What could make them cry?

What is the worst thing they could do?

What is their fantasy of home?

Bedroom: what it looks like and how they sleep

Sex life

Dining/living room what it looks like and what and when they eat

Entertain-How?

How do they do housework or not?

How do they walk, use gravity-lightly, heavily, sideways, gingerly, confidently

Exercise outdoors-what do they do in the Gunks?

How do they take care of their homes?

What kind of car do they drive, or not?

How would their obituary read?

On the shades of hot to cool, what color are they?

What kind of politics do they subscribe to?

Why? And does this change?

How do they groom themselves and what would they like to look like?

Sense of humor

Religious or spiritual faith

Protagonists are the protein--they build muscle, repair tissue, require lots of water to digest, and have the most long lasting effects on the audience's metabolism.

Proteins can be meat, fish, nuts, legumes, or dairy products.

If your main character is modeled on milk, how would that differ from a steak protagonist?

Junk food is the antagonist because it slowly poisons us.

Fresh fruits and vegetables are the friends, allies, and mentors.

There is a difference between the refreshing but watery taste of a cucumber, the challenging crunch of a cauliflower or broccoli stalk, and the sweet, squishy sensation of a ripe tomato.

Some vegetables, like asparagus, shallots and beets, taste better cooked, i.e. modified by intense dramatic structure. You know what that means: those are true friends in times of trouble.

Then there are the friends who are as sweet as a ripe apple, or as succulent as a bunch of grapes.

Note that any of these fruits or veggies could still act like a broom, sting like a bee, or sound like an accordion in scenes. That is what gives characters depth and unpredictability.

Grains, rice, pasta, starches are the people who make up the society, or glycogen. The fuel for action. The society.

Our carbohydrates relate to our story because some veggies or starch or plucked from vines or trees, while others are dug up from the soil. Remember to clean those root vegetables thoroughly unless you are writing a memoir.

Some carbohydrates like pumpkins have multiple uses as a dinner starch, a pumpkin pie, or a Halloween pumpkin!

Even though we may not want to get fat, we need fat in our diet to lubricate the tissue, provide energy, and improve organ function. In stories, fat can provide a love interest in action-adventure, comic relief in tragedy, or just that delicious padding that makes our scenes more seductive.

There is a difference between healthy fats like olive oil and ice cream.

We drink bottled or tap water, fresh or canned juices, and sometimes less healthy liquids such as alcohol or coffee. They all affect our assimilation and digestion differently. A social event fueled by liquor creates a different ambiance from one where only coffee is served. How does a bar differ from Starbucks? Or a hiking trip where people just drink water