Renato Strauss

Professor Keefer

August 2, 2000

Emissions Trading � Fact or Fiction?

Photo � Visser/Greenpeace 1991

Skeena Cellulose Pulp and Paper Mill, Prince Rupert, BC, Canada

In the United States, we use free-market mechanisms to limit and control air pollution.� Can we use market forces to help us cope effectively with environmental problems, in the United States and around the world?

In this paper, I will closely examine emissions trading, a free-market mechanism to control industrial air pollution, and prove that it is a more effective method to deal with problems affecting the environment than traditional ways like regulation and taxation.� After demonstrating that emissions trading is a viable solution, I will propose this method as a model to deal with other environmental problems facing us today.

Emissions trading in the United States has its roots in the Clean Air Act, the landmark legislation that was enacted by Congress in 1970 and revised in 1990.� The 1990 Clean Air Act, whose goal is to improve air quality, sets specific pollution targets and deadlines for states, local governments, and businesses.� A pollution permit program was instigated as a way to help the various entities in attaining these goals and to give some �breathing room� and flexibility to industry.� It works as follows: after setting the maximum emission amount for any given air pollutant, an �emissions budget� (Cantor Fitzgerald), the government divides the budget among emitting companies (or sources) by issuing them permits.� The permit lists the pollutant to be released by the source and the exact quantity of the pollutant that it is allowed to release.� The source�s permitted amount of pollution is usually determined by its past emissions volume and plant capacity but political and legislative concerns can also affect the allocations.� Since the maximum amount of the pollutants to be released is predetermined by the Clean Air Act, the aggregate amount of air pollution allowed by the permits cannot exceed that level.� And most importantly, since the �raison d��tre� of the Clean Air Act is the incremental decrease of air pollution, the total emissions budget for any given air pollutant is reduced on a yearly basis.

Emissions trading is a direct result of the permit system.� Any company that is subject to the permit system will be confronted with three basic scenarios: (1) the company can simply release the amount of pollutants allowed by its permit; (2) it can reduce or eliminate the emissions and sell the �unused� part (or emission credit) of its permit to a third party; or (3) it can increase its emissions, but then will have to buy emission credits from a third party to make up for its excess release.� In order to stay within the limits set by the emissions budget, newly formed polluting entities are not entitled to a pollution allocation, and therefore, need to buy credits on the open market in order to operate.

Emissions trading applies the laws of supply and demand to pollution control.� Assuming that trading is properly regulated and supervised, market forces are the ultimate determinant of the economic viability of producing polluting emissions.� By assigning a monetary �value� (emission credit) to pollution, it is turned from a �negative� into a potential valuable tradable commodity.� The mechanism of selling emission credits on the open market creates a powerful economic incentive for operators of polluting plants to reduce their emissions either by switching to less polluting technologies or by shutting down their operations.� On the other hand, if a polluter chooses to increase his emissions, he will incur an economic penalty by having to buy extra credits.� If there is a large imbalance between the supply and demand of emission credits, the cost of polluting can become substantial, and will encourage the development and deployment of previously economically unviable, but non-polluting, alternative technologies.

Emissions trading gives industry flexibility to comply with the limits set by the Clean Air Act.� Instead of being forced to cut back or even shut down their operations, industry is given a mechanism to continue operating, thus limiting the potential disruptive effects of having to cope with the emissions budget as determined by the Clean Air Act.

One key provision of the emissions trading concept is the pre-set total emissions budget.�� Trading in any given pollutant cannot start unless its corresponding emissions budget is set.� This �cap and trade� (Gelbspan 3) mechanism ensures that pollution is kept in check.� Since the budget is set to gradually decline, the positive environmental impact is reinforced with the passing of time.

Emissions trading achieves substantial cost savings as compared with alternative methods of controlling air pollution.� For example, the cost savings of the sulfur dioxide (SO2) program for the Los Angeles basin was �as much as 50 percent or more compared to a control policy in which no trades were allowed� (Tebo).� Nationwide, �compared with a traditional regulatory alternative, the fully implemented SO2 market has generated cost savings of up to $1 billion annually� (Council Of Economic Advisers 259).

In the United States, emissions trading has occurred for a number of years.� Labor and industry favor trading because of the flexibility it provides to polluters.� Politicians like it because they do not have to pass alternate potential unpopular solutions like pollution taxes and �onerous� rules and regulations.� Most economists favor trading because of its �market-based approach� (EPA Publication).� And some environmentalists favor this system because of its provisions for gradually declining total emission limits, a process which should assure improved air quality.

The mechanism of emissions trading is not devoid of problems.� Leading environmental organizations charge that well capitalized industries can simply �buy themselves out� of their responsibility to clean up their operations.� This may be so in isolated cases.� However, since overall emissions are capped, and therefore, the supply of pollution credits is limited, the high costs associated with the large-scale purchase of pollution credits will greatly decrease the likelihood of industry doing so.

The limited flexibility emissions trading provides for industry can lead to local distortions.� In an extreme case, a company could decide to consolidate its polluting emissions in one location by allocating its total pollution allowance to this single site.� Limitations on the volume of trading to and from clearly defined geographic areas are required to limit this sort of potential abuse.� In order to assure a properly functioning emissions market, rules and regulations are a definite necessity.� However, a careful balance has to be found.� �Excessive regulation could seriously hinder the development of an efficient market in emission permits� (Council Of Economic Advisers 254), and therefore could prove counter-effective.�

Since trading in some emissions markets is not only limited to polluting companies, there is a potential for excessive speculative trading by third parties.� Trading needs to be properly supervised to keep the market�s integrity intact and to minimize the possibility of market-distorting speculative attacks.� Rules and regulations similar to those passed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to supervise publicly traded equity markets can be used to ensure properly functioning emissions trading.� An effective enforcement mechanism is needed to create enough deterrence for potential violators.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and various state agencies are responsible for the allocation of pollution permits to emitting companies.� The proper supervision of this process is essential to prevent political manipulations of the allocation process and to assure the fairness and integrity of the system.

Emissions trading is, of course, not without controversy.� The Sierra Club advocates alternative, incentive based solutions like pollution taxes, or in reverse, tax credits for the use of non-polluting technologies (Waid).� While in isolated cases taxation can be an effective method to propagate the use of alternative technologies, in today�s political climate, taxation is extremely unpopular, and politicians advocating new taxes stand little chance of re-election.� Tax credits for once are not a solution.� According to an analysis by the Energy Information Agency, tax credits proposed by the Clinton Administration to encourage the development of energy efficient technologies like solar energy systems (expected to total $4 billion over five years) will reduce carbon emissions by 1.3 million metric tons in 2010, representing a reduction of only 0.07 percent below carbon emission projections for that year (Thatcher).

Others favor �command-and-control� (Weathervane) approaches like the passing and enforcement of laws and regulations.� However, regulation, the traditional way of controlling any kind of environmental problem, in most cases, has been unable to make a significant contribution in the fight against pollution.� Commerce and industry generally oppose and actively lobby against new rules and regulations.� Enforcement is expensive, especially in comparison with marked-based methods like emissions trading.

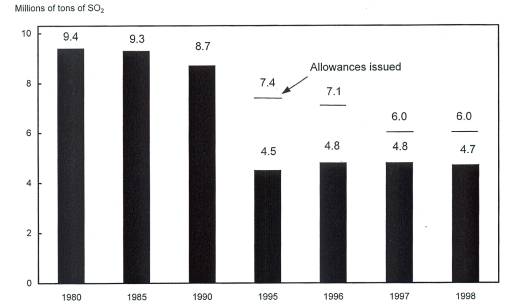

In the United States, the marked-based approach of emissions trading seems to be working without compromising the environment.� For example, Phase I of the Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) Trading Program, covering the 110 highest emitting coal-fired power plants (representing 263 units) in the Eastern and Midwestern United States.� Beginning in 1995, emissions of SO2, a major cause of acid rain, were capped, and trading was instigated.� As the chart below demonstrates, the �cap and trade� mechanism has worked exceedingly well.� It is well worth noticing, that during the �control and command� period, stretching from 1980 to 1995, reductions of SO2 emissions were minuscule.� In 1995, the first year of �cap and trade,� there was a dramatic reduction of emissions.� Although emission levels have stabilized since then, mostly due to a strong economy, 1995 to 1998 SO2 emissions are clearly below their respective �cap� levels.

Emissions from Phase I Facilities in the Sulfur Dioxide Trading Program

�SO2 emissions from the original 263 units have fallen well below binding targets� (Council Of Economic Advisers 260).

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Some environmental organizations oppose domestic emissions trading.� The Sierra Club charges that some emissions trading programs do not account for weather patterns and different emission standards in neighboring states (Waid).� For example, New York SO2 emission standards are more stringent than Ohio (and the limits set by the SO2 program).� This allows New York polluters, who, thanks to these strict local pollution limits, have excess pollution allowances under the SO2 program, to sell their permits to Ohio plants, where local laws allow greater emissions.� Thanks to the Jet Stream, the prevailing wind pattern, Ohio emissions are being blown eastward, causing massive acid rainfall in New York State.�

In this case, the Sierra Club�s argument carries weight.� The SO2 program, while successful in reducing emissions, has some structural flaws.� As discussed earlier in this paper, emissions trading is most effective if emission limits are standardized throughout its applicable area.� As is the case with New York and Ohio in the SO2 program, differences in emission limit standards will cause local distortions.� Furthermore, wind patterns need to be considered when designing a trading program.�

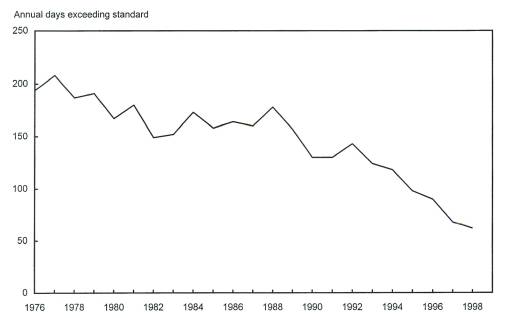

A working example of a well-designed permit trading program is the Southern California Air Quality Management District�s Regional Clean Air Incentives Market (RECLAIM).� This program, covering SO2 and NOX (nitrogen oxide) emissions, applies the same rules to all polluting facilities in its area.� To account for prevailing wind patterns, RECLAIM divides the Southern California area into inland and coastal zones.� �Permits can only be sold from coastal zones (upwind) to inland zones (downwind), not vice versa� (Council Of Economic Advisers 258), thus preventing excessive air pollution in downwind areas.� As shown in the following chart, RECLAIM can be considered a successful, well-designed trading program.

South Coast Air Basin Exceedances of Federal Ozone Standard

�Southern California exceeded the Federal ozone health standard on roughly one-third as many days in 1998 as in 1980 and half as many days as in 1993� (Council Of Economic Advisers 258).

Source: South Coast Air Quality Management District

Although emissions trading has shown to be an effective mechanism to combat air pollution, most environmental organizations, such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club, are still opposed.� Some of their reasoning is more philosophical than based on facts.� They greatly distrust industry and regard the clean air issue as a war between �good and evil� (Simmons).� In a war, there is no room for negotiation or cooperation, and complete victory is the only solution.� �Many in the environmental community will settle for nothing less than a complete shut down of most of the coal-fired generation in the nation� (Wojick).� The idea of fighting pollution by cooperating with industry through a permit trading program is unthinkable.

This absolutist approach carries big risks.� In a war scenario, victory can be achieved, but there is also the possibility of defeat.� In industry and commerce, the environmentalists have chosen a formidable enemy, who will not just lay down their arms.� On a critically important issue like air pollution, would not compromise and cooperation (or diplomacy) offer a better solution?

The relative success of emissions trading in the United States has spurred calls to take the �cap and trade� mechanism global.� The Kyoto Protocol of 1997, which orders 38 industrialized nations, the OECD (minus South Korea and Mexico) plus the countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by a total level of 5.2 percent between 2008 and 2012 from 1990 levels, proposes international emission trading as a key �flexibility mechanism� (Kopp and Toman 1) to help the signatories achieve the agreed on reductions.� Environmentalists, led by Greenpeace, are voicing strong opposition.� They claim that wealthy industrialized nations like the United States, in order to comply with the Kyoto Protocol, will ��trade� away the environment, jobs and clean air� (Greenpeace USA) by simply buying emission credits from poor, less industrialized countries, thus avoiding �real� but potential painful measures to reduce greenhouse gasses at home, like the use of alternative energy sources or the closing down of polluting plants.

There is no question that undertaking emissions trading on a global scale is a complex and difficult endeavor.� The fact that a large number of countries with widely diverging economic and political interests are participating in this program creates systemic tensions.� On one side, we have the US, the strongest proponent of unlimited free-market trading.� Western Europe does not oppose trading per se, but puts more emphasis on Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol, which states that this trading �shall be supplemental to domestic actions� (Kopp and Toman 1).� Western Europe and Environmentalists question if the US has any intention to meet the �supplementary� (Kopp and Toman 1) part of the Kyoto Protocol.� There are estimates that the US will �take the easy way out� and buy up to 85 per cent of its �reduction quota� from poorer nations, in order to comply with the cuts of the Kyoto Protocol (Kopp and Toman 1).� China and India, which are not covered by the Kyoto Protocol but have the option to participate if they set national pollution reduction targets, are questioning the fairness of the pollution allocation process.� They charge that allowances should be determined on a per capita basis, and not on historical emissions which benefits industrial powers like the US and high pollution countries in Eastern Europe to the detriment of densely populated and undeveloped nations of the Third World.�

All these arguments carry some weight.� It is clear, and US trading programs have shown, that unregulated and unlimited emissions trading will not work.� There will be a need for trading limits to prevent �rich� countries from buying wholesale trading allowances from Third World countries.� National emission regulations have to be standardized over time to prevent market distortions.�

The question of the fairness of the pollution allocation process is difficult to answer.� One can debate, ad infinitum, that undeveloped and overpopulated nations with relatively small allocations will be unable to raise their standard of living by industrializing, while rich, developed countries with high allowances will be able to keep their high-living, high-polluting ways.� However, we have to keep in mind that to reverse this situation would be to the benefit of no one.� The United States, Japan, and Western Europe are the economic �locomotives� of the world.� Third World countries desperately depend on trade with the developed world.� Curtailing development in industrialized nations would create enormous economic disruptions and would benefit no one, least the countries of the Third World.

On the other hand, emissions trading will create a new export item for Third World nations - emission allowances.� �Developing countries could generate billions in revenue annually through the sale of emission allowances� (Council Of Economic Advisers 268), which could be used by these nations to improve their economies and standard of living.� Furthermore, in order to economically advance, �developing economies do not need to go through the phases of heavily polluting industrialization, that most of the advanced economies suffered� (Anderson).� Sustainable development that does not harm the environment might be the best answer for Third World nations.

To finally judge the Kyoto trading mechanism, it is worth taking a look at the �big picture.�� Global air pollution is a serious problem.� There is ample evidence that it is the prime cause of global warming.� While Kyoto, and its accompanying trading program provide for modest total emission reductions, it is none-the-less an unprecedented and encouraging start.� For the first time since the age of industrialization, the international community has decided to take concrete steps to limit the emission of harmful pollutants.� Kyoto will never satisfy hard-core environmentalists who favor a 70 percent cut in global emissions (Gelbspan 1).� However, if implemented successfully, Kyoto will be an important weapon in the fight against global warming.

Over the course of this paper I have demonstrated that emissions trading is an effective method to limit air pollution.� This free-market mechanism could be applied to a number of environmental problems.� One area is garbage disposal.� In the United States, an average person generates 4 pounds of garbage per day (Council of Economic Advisers 261).� Generally, garbage is either burned in incinerators or dumped into landfills, creating numerous environmental problems �such as water pollution (from landfills), or air pollution (from incinerators), and transportation-related problems associated with hauling waste� (Council of Economic Advisers 261).� Furthermore, due to the ever-increasing volume of garbage, existing landfills are rapidly being filled to capacity.� In today�s political climate, it is nearly impossible to gain approval for new landfills (or for that matter new incinerators) near populated areas.� Although recycling is becoming more popular, to date, it has failed to reduce the volume of garbage piling up in landfills or being burned in incinerators.� Therefore, an incentive-based allocation trading program might be a viable solution.� We could set an initial garbage allocation budget according to current volume (4 pounds per person per day), thus setting a limit on the total amount of garbage being produced.� As is the case with other allowance programs, this budget can be gradually reduced over a set amount of time.� A family of five would have an initial daily waste permit of 20 pounds a day.� As with air pollution, if this family chooses to produce more waste, it would have to buy extra allocations from a third party.� If the family chooses to recycle more of its waste products, and therefore generates less garbage, it will be able to sell the �unused� part of its allocation to a third party, generating extra household income.� Although garbage disposal has different characteristics than air pollution, and a well-designed garbage trading program would have to account for these differences, on principle, allocation trading could be helpful in incrementally reducing household waste.

This method could be applied to additional environmental problems.� We could create housing allocations to combat urban sprawl, or automobile allocations (based on fuel economy) to reduce air pollution and highway congestion.� In fact, the state of Alaska, through TAC (or total allowable catch), addresses problems such as declining fish stocks due to excessive commercial fishing by setting a fishing budget and allocating permits to participating fishermen (Council of Economic Advisers 264).�

In the course of my research, I have been struck by one recurring fact about emissions trading.� By assigning a value to a problem, we create an economic incentive to reduce (and ultimately) solve a problem.� By doing so, we create a mechanism which involves the widest possible audience.� Nowadays, who does not want to earn extra money?� In other words, an allowance trading program does not require its participants to be concerned about the environment in order to succeed, it needs �regular people� willing to �make an extra buck,� or for-profit corporations looking to increase their bottom line.� Because the �widest possible audience� is involved, we create conditions where the ultimate goal, the solution of these difficult environmental problems, can become reality.

The concept of emissions trading is relatively new.� Most programs have only been operating for a few years.� Some opponents claim, that because of the novelty of emissions trading, we cannot bear the risk to test this method on critical environmental problems.� Judging from the success of some allowance trading programs, and taking into account the shortcomings of traditional methods, it seems to be a risk well worth taking.

Works Cited

Anderson, John. �White House Says Emission Limits can Bring Huge Benefits to Developing Countries.� Weathervane. A Digital Forum on Global Climate Policy. February 22, 2000. http://www.weathervane.rff.org/features/feature049.html. retrieved online July 24, 2000.

Council Of Economic Advisers. Economic Report of the President. Washington: GPO, February 2000.

David Waid (Sierra Club, New York City Chapter). Telephone Interview. July 20, 2000.

Gelbspan, Ross. �In Focus: The Climate Crisis and Carbon Trading.� Foreign Policy In Focus July, 2000.

Glossary. Weathervane. A Digital Forum on Global Climate Policy. 1998. http://www.weathervane.rff.org/glossary/index.html. retrieved online July 11, 2000.

Greenhouse Gas Trading and Global Warming. � 1997 Cantor Fitzgerald Brokerage. http://www.cantor.com/ebs. retrieved online July 9, 2000.

Huber, Peter. Hard Green. Saving The Environment From The Environmentalists. A Conservative Manifesto. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Kate Simmons (Sierra Club, New Columbia Chapter). Telephone Interview. July 20, 2000.

Kopp, Raymond and Michael Toman. �International Emissions Trading: A Primer.� Weathervane. A Digital Forum on Global Climate Policy. October 1, 1998. http://www.weathervane.rff.org/features/feature049.html. retrieved online July 9, 2000.

Latest White House Analysis on Kyoto Treaty: �Trading� Away Environment, Jobs, Clean Air. Greenpeace USA. July 31, 1998. http://www.greenpeace.org. retrieved online July 9, 2000.

Tebo, Michael. � International Emissions Trading Offers Both Benefits and Challenges.� Weathervane. A Digital Forum on Global Climate Policy. June 5, 1998. http://www.weathervane.rff.org/features/feature040.html. retrieved online July 9, 2000.

Thatcher, Jennifer B. �EIA Analysis Reveals CCTI Will Have Small Impact on Emissions.� Weathervane. A Digital Forum on Global Climate Policy. May 11, 2000. http://www.weathervane.rff.org/features/feature096.html. retrieved online July 24, 2000.

The Plain English Guide To The Clean Air Act. EPA Publication. 1993. http://www.epa.gov/oar/oaqps/peg_caa/pegcaa01.html. retrieved online July 10, 2000.

Wojick, David. � Four Factors Suggest a Big Change in the SO2 Allowance Market.� The Emissions Trader. January 2000. http://www.emissions.org/newsletter/jan00/wojick.html. retrieved online July 13, 2000.

Back to syllabus