Visual comparison of Don DeLillo’s White Noise

and Diane Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses

Visual comparison of Don DeLillo’s White Noise

and Diane Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses

It is mainly through seeing the world that we can evaluate it and understand it, but “like supreme racehorses, full of vitality, determination and heart we tend to miss sights not directly in our path...” (Ackerman 235) Ackerman reveals to us a new way of experiencing sights - the ever present sky, “a complex backdrop to our every venture, thought and emotion”; the wind which sculpts the landscape; the sun’s white light which brings to us a spectrum of colors and subtlety influences our moods. Ackerman’s venture into vision is sensuous in its presentation and through her we make the connection to our natural environment and thus are able to better appreciate the experiences.

We tend to think of our

eyes as seers but seeing really happens in the brain as we remember things

past in our mind’s eye. Our language is steeped in visual imagery,

as is evident in White Noise where we rely on our mind’s eye to

capture the action the vivid images described. Don DeLillo is more

physical in his descriptions of the environment. We are able to reach

out and touch the images and though we do not make a sensory connection

as with Ackerman, we do learn a new way of experiencing the world around

us.

“The charm of language is that, though it’s humanmade, it can on rare occasions capture emotions and sensations which aren’t.” (7) Our language is steeped in visual imagery, as is evident in both White Noise and A Natural History of the Senses, where we rely on our sense of vision to capture the action or the mood. Ackerman describes the sights she encounters in such vivid detail we experience it as though we are present and are able to think our way back into feeling. Through the senses of touch, taste, hearing, smell, and vision, we get to know life intimately and perceive the world differently. The way we perceive and respond to color is unique to humans, yet animals use this silent language in the form of camaflouge to ensure their survival. Smell warns us of impending dangers, signs of illness or alerts us to a lover or child nearby. It has even contributed to the spread of languages as merchants crossed the oceans to trade spices and perfumes and had to haggle and keep records once they arrived there. Hearing, taste and touch intermingle so we better appreciate the texture and appearance of life in the natural environment. Ackerman shows us that our senses connect us intimately to the past and “unite us in common field of temporal glory...” (302)

“Much of our experience in 20th century America is an effort to get away from those textures, to fade into a stark, simple, solemn, puritanical, all-business routine that doesn’t have anything so unseemly as sensuous zest.” (XVIII) This seems to be the definition of life in White Noise where their senses are numbed by the t.v. and nature is replaced by malls and grocery stores where everything is neatly arranged and labeled. Even the sex life of the main characters, Jack and Babette Gladney, is taken out of its natural environment and reduced to reading from a wide ranging collection of pornographic literature for stimulation, “Pick your century. Do you want to read about Etruscan slave girls, Georgian rakes?... What about the Middle Ages?” (DeLillo 29) This removes the eroticism from their existence, from the way it was meant to be leaving it cold and antiseptic.

The characters in White Noise live in an environment produced by advanced technology - the holographic scanners at the supermarket, the personal computers, the stereo sets and radios which all determine their quality of life and ultimately, as seen when the agent from SIMUVAC punches in a few numbers and gets Jack’s history, how they die, though the actual time cannot be computed.

“CABLE HEALTH, CABLE WEATHER, CABLE NEWS, CABLE NATURE.” (231) Nature is reduced to being on cable, readily available to anyone who has access to a television. Nature ceases to exist as an order that once transcended man and is now something that man has complete and godlike control of. It is no longer necessary to visit the land and commune with nature; it is sufficient to turn on the t.v. and nature is available at the touch of a remote. Nature is something to be managed and controlled “the environment is in man’s keeping and control, and it is his responsibility to administer it according to a modern scientific understanding of the world.” (Lentricchia 66)

Stereos, hairdryers, hunk food - generic objects and events, things seen everywhere and all the time, “relentlessly repetitious experience....With perception so grooved on the routine, the affective consequence follows rigorously...boredom, an evaluation of spirit, an intimation of a Hell.” (95) There is a disconnect from the environment and in so doing their life of consciousness is deprived; dulled and eventually dead. So ingrained is technology in their lives that even in her sleep, one of the children, Steffie, utters ‘Toyota Celica’ - repeating what she had heard on television a million times that had become part of her ‘brain noise’.

Both novels give us an appreciation of our environment, DeLillo’s on a physical, technological plane and Ackerman’s on a sensuous level. “We need to return to feeling the textures of life” (Ackerman XVII) to fully enjoy the diversity of human experience and enjoy life as a whole and not in fragmented, separate sections.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackerman, Diane. A Natural History of the Senses.

Chelsea House Publishers: New York, 1987

DeLillo, Don. White Noise.

New York: Penguin Books, 1986

Lentricchia, Frank. New Essays on White Noise.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991

Interleaf

of DeLillo & Ackerman

Interleaf

of DeLillo & Ackerman II - The Airborne Toxic Event

Chapter 21

(DeLillo 107)

Heinrich watches, black billowing clouds, mylex suits, SIMUVAC, people waiting till it's too late, etc...

by Michael Harkins

The sub-atomic family that inhabits Don DeLillo’s White Noise would be humorous to behold if it were not so frightening to look into their “so-called” lives. Feigning family life, these people no more resemble a “family” than the bizarre life forms that mutate around drums of nuclear waste that sit just off the California coast. Strange, monstrous, overburgeoning growths that have too much energy at their disposal, but maintain a semblance of what they once were.

Man has truly advanced - he has split the nuclear family. Children are bounced between multiple parental units like exotic particles with short half-lives careening across vast distances. The home of Jack and Babette Gladney is not a hearth, but a cyclotron, pumping enormous energies into their offspring who will in turn spring off them at phenomenal speeds. Crashing into other such charged “particles,” one can only speculate what new, shorter-lived particles will result. One could imagine quark-like emanations in the form of fractured personalities inhabiting the cloud-chambers of insane asylums.

Something is wrong in DeLillo’s Middle America. Aside from the frazzled bonds that barely link these step-lings, and the psychological cornucopia of energies unleashed by such an implosion of fissionable family members, the Gladneys are bombarded by a culture that is itself collapsing under its own surplus production of products, by-products, waste, exhaust, heat, information, transmissions and energies. These poor, soul-less, automatons, mindlessly go through the motions of a life. They pay homage to the oracle of talk-radio and keep the eternal flame of television ever-burning, but there are no gods in their health-conscious, junk-mail, tabloid, pseudo-science world.

Automatons is the best word to describe them. We all know the storyline - mind is transferred into machine and one can no longer sense the world. There is no taste or smell, everything appears grayscale, a hissing tinny monophonic dull roar surrounds us, and, aside from the pressure and weightedness of things, we no longer feel. Then comes the stark realization that the sensate world is what gives life its meaning. Without senses the bland, cardboard, stuffs we stuff ourselves with no longer sustain us, and like junkies that need ever larger doses, we constantly look for more and more abrasive textures, flavors, aromas, images, and sound is replaced by shear noise.

The tiny-town innocence of White Noise, with the "College-on-the-Hill," is immediately threatened. “There are houses in town with turrets and two-story porches where people sit in the shade of ancient maples...There is an insane asylum with an elongated portico...” (DeLillo 4) Later, father and son will have a Kodak moment in front of that asylum watching “a woman in a fiery nightgown...mad, so lost to dreams and furies that the fire around her head seemed almost incidental.” (DeLillo 239) They’re all mad in this fabricated suburb, all on fire, consumed, insensitive to the inferno that surrounds them, about to collapse.

Like an oasis, Diane Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses replenishes the soul, dried out and cracked by the harsh, blasting desert of DeLillo’s Noise. Transported to some elysian plain by Ackerman’s words, we re-enter our subtle body. She restores us piece by piece, sense organ by sense organ, until the greater whole is brought back to life in a synesthetic enlightenment. Curled up with this good book we peel away the inauthentic mummific trappings of the embalmed existence we call modern life, and dream of waking in a living world.

Such dichotomy, between

Ackerman and DeLillo, we imagine is necessary. We might think that

extremes are all around us, tropics and tundra, dry land and stormy seas,

flora, fauna, concrete and steel, but too many of us live in DeLillo’s

world. The Eden Ackerman paints is fast becoming a distant memory,

a not-so-easily reached haven that many of us have lost. What gives

us hope is the way Ackerman, the wise serpent, insists that this world

is within reach, if we but hold out our hand. Any flower shop or

farmers market will fill the senses with a world of sights, smells and

textures. The very flavor of life is at the nearest apple,

and the crisp snap of that first bite might just wake us from our stupor.

Bibliography

Ackerman, Diane. A Natural History of the Senses.

New York: Random House, 1990.

DeLillo, Don. White Noise. New York:

Penguin Books, U.S.A., 1984.

Our senses are our link to the world around us and our primary means of communication with the sentient universe. Necessary to our survival as individuals, they have “guide[d] us down the...corridors of evolution” (Ackerman 63), giving our species formidable advantages, and enriching our lives with an array of sensuous experiences. However, in our modern world of smog, concrete, jackhammers, and chemical waste, our senses are both constantly assaulted to the point of becoming desensitized and starved for the organic richness of the natural world.

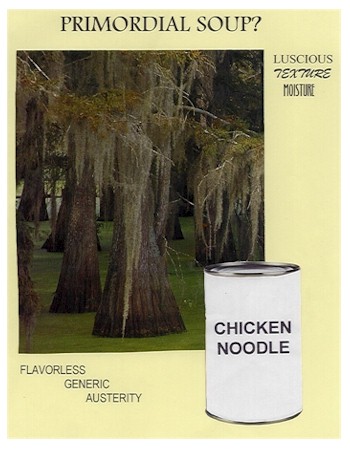

In our drive towards prosperity and efficiency, ours has become “an effort to get away from textures, [and] to fade into a stark, simple, solemn, puritanical, all-business routine...” (xviii). Our cities, towns and even our farms reflect this inclination; one only needs to look at the glass, steel, and concrete boxes we call skyscrapers, the rows of insipid, perfectly manicured lawns of our suburbs, the “nonbrand items in plain white packaging with simple labeling” (DeLillo 18) found in our supermarkets, or the orderly rows of Holsteins being milked by metal tubes in the technologically advanced barns of our rural landscape.

Most of our daily routines seemed to be either violent assaults to our senses, or the means by which they are slowly deadened. We are awakened by a shrieking alarm or the loud drone of a radio DJ who has drunk too many cups of coffee; take a few seconds to let our heartbeat go back to normal, and then rush through our daily grooming routine, pausing only to take in our own dose of the cherished stimulant. We then find ourselves either in a crowded bus or train–encased in a cocoon of inattentiveness, or in the solitude of our own automobiles–sharing the road with a few million other solitary travelers, while listening to the discordant symphony of blaring car horns. Arriving at our destination, we enter the environmentally stable world of our office buildings. There we are surrounded by the muted colors of the walls, carpets, and furniture, while the windows to the outside world are those of a computer program. Occasionally, some of the most daring among us will bring a bouquet of flowers to add a little color and fragrance to the surroundings, only to realize that the perfume has been bred out of them, so we settle for the aroma of stale coffee, chemical emissions of the copiers, and trendy new fragrances worn by our co-workers. Most sounds are also muted, with the few exceptions of the motivational soundtracks of the motivational videos we are asked to sit through every so often.

Some of us have been so insulated from the natural world that it has become alien and something to avoid, even fear. However, most of us yearn for those small slices of time when we can “go back” to nature and reaffirm our propinquity with the earth. For some there are few things as magical as an excursion to the beach, sometime before reaching the actual shoreline, the breeze is saturated by the sea’s briny fragrance and as it engulfs us, we feel a soothing sense of joy, perhaps we are taken back to a long forgotten time when “we thrived in the oceans” (Ackerman 20). We may also choose to hike through the forest listening to the splashing water of a crystalline stream, songs of birds calling to their mates, or leaves rustling in the wind. As we come to a clearing, we pause to take in the rich textures and colors of the trees, letting them “conduct [our] eye from the ground to the heavens” (240). As we look at the sky, we “link the detailed temporariness of life with the bulging blue abstraction overhead”(240); and fleetingly our bodies remember our quintessential nature and we savor the sweet taste of belonging, though all too briefly, to something wondrous.

Works Cited

Ackerman Diane. A Natural History of the Senses.

New York: Random House, 1990.

DeLillo, Don. White Noise. New York: Penguin

Books, 1984.

I envision the airborne toxic event not being toxic at all but fragrant. As the vapor clouds travels closer, you get a faint whiff of roses, until you are engulfed in the sweet, intoxicating scent of roses. There is not a feeling of dread as in a toxic event, but of warmth, security and love because of the fragrance. The cloud does not sicken you or cause disease; instead it will heal your mind, body and soul.

The scent of roses envelopes you and an image pops into your head. The image of your lying naked on a bed of rose petals, while more petals are raining down on you, gently caressing your skin. The smell makes you dance around and allow all your senses to absorb every sensation like a newborn child.