Who owns the story? America's televised battle for cultural supremacy

by Ellen Turkenich

It has been said that war is often fought on two fronts - one, the actually

physical campaign of combat, and the other, the psychological campaign

of winning the 'hearts

and mind.' The three week war in Iraq known as Operation Iraqi Freedom

proved no different. It was not just about America's war for oil or the

liberation of the oppressed, but it represented a global television war further

expanding the American corporate hegemony onto the cultures of the Others. From

March 20th to April 9th, the round-the-clock television bombardment into American

and Arabic homes of computer guided missiles and killed civilians has become

the discourse by which most of the world has come to understand the realities

of warfare. The interplay among the American commercial news channels/military

storytellers, Al-Jazeera, and the other 'responsible' Western broadcasters

has been a confrontation of relative values concerned primarily with whose narrative

can dominate the coverage of the event, and in essence, dominate the psyche of

the public arena. In this mediated clash, truth ' the value, the ownership,

and the relativity ' become the weapons for the battlefield of cultural

supremacy. As televised wars in the future will continue to play a seminal role

in the arsenal of war, what is needed in the post-war coverage analysis is a

deeper

examination

of the television's role in propagandizing war and an understanding of

the televised effects.

The uniformity in American television channels of the initial 'shock and

awe' military bombardment foretold much or what was to happen: a lack

of in-depth and differentiated criticism of American foreign policy. What Americans

wanted was a good story that they could follow and have come to depend upon in

television. While propaganda is considered an ugly word in America's free

press circles, the televised bombardment came as close to it in its self-censorship.

Reporters pride themselves on a heroic independence, as champions for accountability

with dozens of associations and charters to insert independent and assumingly

objective coverage into the news stations. For those who viewed the war coverage

on CNN and FOX during the first week of the war, they would universally attest

that there has never been such a greater insertion of war correspondents as participants

in the field of battle with almost eerie homogenous results. Whether the viewer's

choice was Brett, Dan or Peter, the main focus

became the visual display over Baghdad. On the first day of the US lead war (March

19th), both FOX and CNN showed the war's opening ceremony from the same

vantage

point:

the 'shock

and awe' campaign from the rooftop of the Al-Rashid hotel with brief cutbacks

to the anchor desks and Pentagon briefing centers. Cloned journalists replicated

the stories on all the other local and national news desks. It was an 'instant' classic

shot to be replayed repeatedly over the course of the war. Of course, for the

journalists, mimicking Americans at home, the war gave little sense of the Other:

the human residents of Baghdad.

The distancing between us (the perps) and the victims (Iraqis) was necessary

in that we were clearly were the aggressors. Without the upper hand in the human

dimensions of the story, American broadcasters tended to rely more on the fun

and games aspects of war. From first week of the war, following progress of the

military tactics of the 'shock and awe' campaign became a favorite

for CNN: First, with the running commentary on the nightly aerial bombings in

visual terms of fire lit skies and then, with the alert readings such as 'Shock

and Awe postponed,' 'Shock and Awe begins,' and other status

checks. The 'tune in next time' nail biting cliffhangers of the war

were more to command the narrative rather than driven by actual news events.

This heightened sense of events, or hyping the events in real time has more

to do with the unique visual qualities that television can provide. Television

is

powerful because it dislocates the 'viewer' in a full auditory sensation

that is an 'all-at-once' medium, designed to connect the 'viewer' to

the experience of viewing, not necessarily to the content of the medium. This

distinction is held clear in print media. It implies a linear, sequential, and

implicitly, more logical, medium that can be examine at our own pace and leisure.

Logical sequencing is not necessary, and in fact, counterintuitive to the television

experience. The medium then is the message. (Berger 18)

This argument is echoed by Benjamin Barber in 'Jihad vs. McWorld' on

the perils of TV viewing in this commercial age. Television is a tool designed

not for any civic purpose but notably to adulterate humans for material consumption.

(111) It refers to the ability of television to create a hyperkinetic response

through images that overpower the sensory framework. The effectiveness in creating

the consumption identity comes from exciting the most unconsciousness human drives.

Commercials often trade on instinctual triggers based either on sex or violence,

eliciting a 'Pavlov's' response to stimuli that eludes logical

decision making. It conditions the mind to accept hyperbolized bits of information

extolling its urgency and immediacy. However what is notable about the television

mediated culture is the blurring between the symbols that represent reality and

the reality itself. The orgy of

images or instant gratifications that satisfy once, only serve to create more

compulsions for 'the instant.'

Whether good or bad, television and commerce as the American way has been

exported across the globe. The creation of open markets has brought international

media

conglomerates that use their economies of scale to operate in every possible

marketplace. In US alone, the top three media firms have captured over 80% of

the viewing public. The lessons learned by AOL-TimeWarner and Viacom are re-populated

elsewhere as international media firms begin to devour into one another. While

viewers believe that there is choice in programming, the programming comes from

the same corporate mind set. The choice is the choice of consumerism. Corralled

by the lack of real 'choice', the viewer is just branded 'Am

I a CNN viewer or a FOX viewer? Am I a Pepsi or a Diet Coke?

Television as a 'soft power' embodies coercive attributes that are

easily co-opted by hard power elements in society. If there is a connection between

television as the engine of capitalists, then parallels can be drawn between

the cultural apparatus held by media monopolies and the military apparatus held

by industry of weapons manufacturers. In 1961, President Dwight Eisenhower spoke

about the dangers of the undue influence of private interests over the military

industrial complex. His warning spoke of the encroachment on American freedoms

brought by the 'disastrous rise of misplaced powers.' Clearly McDouglas

and McWorld are linked.

So what role does television play in televising the military apparatus? I

suggest that it is the evolution of the military-entertainment complex.

One striking

feature of the war coverage is the preponderance of airtime spent by the

FOX channel, as well as many other network news outlets, highlighting

America's

weapons of destruction: the Hellfire missile, the Stinger, the Daisy Cutter,

the bunker buster, and the MOAB. Each new weapon is schematized, displayed

and dissected as to indicate its superior attributes:

the range of the

projectile, the conditions in which it would operate, and the dimensions

of its interior space. The glossy rotating 3D computer simulated

images with gushing

captions have some scholars wondering whether the thrill is the thrill of

the weapons of mass seduction. In an interview

for the Guardian, Linda Williams, a film studies professor at UC Berkeley,

comments:

CNN has this special thing they do whenever they introduce a new weapon. It reminds me of the way athletes are introduced in coverage of the Olympics: a little inset comes out with their bio and stats...it (this weapon) comes flying out and turned this way and that way and that so that you could see it from all angles'This is the kind of spectacular vision you get in porn ' where the point is to see the sex act from every angle. It's narcissistic; boys getting together admiring their toys. It is about us proudly displaying our weapons and there is something sexual about that. (Brockes)

Or is it possible that the coverage is a consumer manual, accompanying the billions

of dollars spent on defense? According to the Pentagon, one tomahawk attack

missile costs about $1million each. In Iraq alone, the United States has dropped

over a hundred in a span of just two weeks. The viewing public can now see their

money well spent on the power and effectiveness of the 'smart' killing machine.

Hints of the efficacy of the military marketing campaign can be seen in a

1991

study conducted by the University of Massachusetts's Center for Studies

in Communication. They surveyed Americans after the 1991 Gulf War on their knowledge

of underlying political issues surrounding the war. Sut Jhally found that those

that were the heaviest television viewers of the conflict were more likely to

support war and know less about the political decisions surrounding the war than

those with minimal TV viewing. However, heavy viewers excelled in one area: a

near perfect recall for the names of military hardware such as the Patriot missiles

and their military capability. Whether the televised Gulf War intended to 'brand' weapons

of destruction, the military did not object in the second Gulf War to increase

televised access to the flight decks and testing centers where reporters could

participate in the firing of American made weaponry.

Weaponry has become a fetish, a commodity that is enjoyed outside of its original purpose. As Jordan Crandall, a media artist, points out:

One wonders, as always, what the real artillery is in this war ' images or bullets. Perhaps the soldiers should be allowed to carry cameras or the camera and gun should simply collapse into one another. It has been narrowing in terms of the windows between detection and engagement, "sensor" and "shooter," intelligence-gathering and deployment -- which in many ways drives military development and especially its aerial imaging. (2)

Vision is outfitted, a retooled weapon.

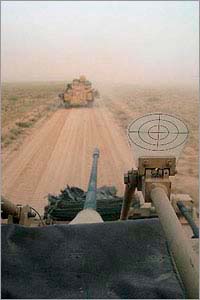

It is no wonder that Americans supported the war, irregardless of any evidence

that the Iraqis were directly involved in the attack of 9-11. In a 'real' sense,

the seamless simulacrum of reality allows us to 'put ourselves on the front

line.' It gives us a sense of participation through the 'real situations' and

the 'real people' or through what is coded as authentic. The voyeurism

is borne on the real-time image streams dislocating us onto the battlefield with

all its implied dangers. They feel that they are under attack, both as the hunted

and the hunter behind the rifle scope. The reaction is from the virtual experience

of having to fear what is unknown in battle. It is the sub-conscious aspects

of the mind that surfaces as we become visual participants, not out of choice

or with any ability to direct the action, but rather from a defensive position

of being held captive.

The April 3rd military re-broadcasting of the Jessica Lynch rescue complete

with Jessica herself inside the broadcast of the press briefing demonstrates

a profound understanding of the media effect. On the surface, the story itself

is that of an American soldier's heroism and bravery. She is extolled as an

example of the new American soldier: A woman who survived combat that was rescued

by other brave Americans in hostile terrain. However, this story is even more

powerful from a narratological analysis.

Viewers are captured by the captured image:

the classic story in story narrative structure. Jessica lies in terror embedded

inside

the screen, by footage taken by others embedded into reporting the story.

General Brooks stands tall in sharp contrast, behind a podium encased

with symbols of

authority and of the nation, acting as the orator. The language surrounding

him extorts us to obey: 'UNITED STATES COMMAND' and reiterates

exactly who is in charge of the coded television messages. He is

the archetype for the

socializing agent that tells the audience what they want to get and who should

give it to them. The audience accepts, entrapped like Jessica in some unknown

terror.

The Jessica Lynch story diminished negative sentiments against the war. After

its airing on the major network channels, the respondents who felt that the war

was going well for Americans increased by 18%. (Field Poll)

In a post-mortem interview with Lynch's colleagues and the Iraqi doctors in

charge of her care, a BBC reporter has debunked most of the heroism attributed

to Ms. Lynch. The extent of her injuries and the ferociousness of her challenge

to her attackers largely been discounted from the original news reports given

by the Pentagon and mainstream press.

As one may surmise, public relations is an acknowledgement that truth is a matter

of perception. Good PR, s well as effective propaganda, involves the telling

of truth, but only a partial truth. It is the control of information, the spin,

that is important, not the content. The true genius behind the war coverage

is Hill and Knowlton, the private PR firm hired by the military to construct

the media/propaganda campaign. It is the ingenuity of their embedded reporting

plan in which the media and military organizers have understood and leveraged

the narrative synergies between television programming and the military.

The incongruity of the reporter's call to arms speaks greater to the emergence

of a military-entertainment complex. From the boot camp that was they attended

to the positions inside combat troops, embedded reporters became the latest

'scud studs.' Appearing out of the sandstorms, the friendly newscasters that

typically read the evening news were now part of the troops. All six excited

CNN embedded reporters took on the language of the 'we' against 'them,' forgetting

that they were impartial observers. Ryan Chilcote, a CNN reporter with the 101st

Airborne Division, personalized his April 14th broadcast further by mentioning

a friend who might have been injured during an attack. Reporting on the hardship

of the troops, the chaos of Iraq, and intolerable sandstorms, reporters seem

to reprise the role of 'friend of the troops.' As a matter of decorum, CNN and

FOX decided against the airing of American causalities and of the numerous Iraq

children and civilians that were injured in the military engagements, all except

for Dr Sanjay Gupta's embedded broadcast of military doctors operating on a

6 year old child. The grisly images of war were too much except when it showed

American beneficence.

On metaphoric level, the embedded reporter gives a good representation

of American monopoly over globalization. The reporter is

dislodged and dislocated from the

cultural anchors of a place and time and embedded elsewhere. The mobile news

reporter represents the ultimate disinterest in cultural specificity and

replacement by the global corporate identity. They know not

the language, the culture, or

the people. Time is also distorted and squeezed down where day and night

exist in the same altered broadcasts beaming from satellites

in Doha and New York.

As the pioneer of the 24 hour news coverage, CNN transmits by satellite to

every major Western market by satellite, and is truly global

in its reach through its

affiliated stations in other parts of the world. Its version of the story

gets played over the newscast of the local market as they

tell the viewers what the

world is watching.

There is some sense of déjà vu from the first Gulf war - a war

which became a televised event with its identifiable cast of characters. During

the first Gulf war, US viewers tuned into see Storming Norman Schwartzkof, Colin

Powell, and Papa Bush. In Gulf War 2, viewers had Rumsfield, Powell, and Bush

Jr. However, central to the casting of this war were the characters revolving

out of the Pentagon's Centcom or the US Command and Operations Center-

General Brooks and General Franks-both of whom dominated official airtime. The

preponderance of military 'talking heads' was hard to ignore. On

the internet site for the media watchdog group of the Farness in Reporting, they

cited over 76% of all 'experts' on network newscasts had

current or past military affiliations or government posts. During a similar

three week

study involving the evening newscasts of six American news channels,

nearly 71% of the American guests were pro-war, but only 3% were anti-war.

Of the featured

British guests, 95% were pro-war military officials with the remaining

5% as journalists. Notably a third of the British public was against

the war at the

time and 27% of Americans had a similar stance, but the anti-war coverage

was minimal. A large percentage of the anti-war appearances were unnamed

or labeled

simply on mass as protesters. With little coverage allotted to the anti-war

voices, it is easy to see that America was unified, at least on television,

for the war

effort. (FAIR)

For those who have experienced the American network television event

will confirm that it represented a new epoch in broadcasting. Grotesque

and riveting,

there

were all the elements that create a good drama ' the conflict, the human

interest, the familiar and reassuring cast of characters, and the unforgettable

villains ' with a good dose of action to keep boys interested

and emotional tear-jerking scenes for the ladies.

However, the success of America's war coverage is problematic. While greater

numbers of viewers across the globe tuned into CNN and FOX, this only highlights

the hegemony of the US over the rest of the world. Sadly, this is a fact apparent

even to the most die-hard supporters of the American way, our Western allies.

It also has polarized those who reject America's message and

fomented greater animosity and fear of US intentions.

Staunch British supporters stayed glue to their televisions as well.

The BBC, the government funded network station, mounted its most

intensive operations

with over 200 journalists and support staff in Iraq and the Middle

East. By American

standards, the BBC was a voice of inclusion. Justin Lewis, a professor

of journalism at Cardiff University, found that the evening war coverage

on

the BBC was most

pro-government out of the three largest British networks, with 11%

of experts from the military and only 22% of the coverage on Iraqi

casualties.

As members

of Blair's cabinet accused the BBC of anti-war bias, Martin

Bell, a post-BBC reporter openly criticized the BBC and other network

news for its one sided depiction

of the war and for not showing the grisly consequences of combat.

More strikingly, the Pew Global Attitudes conducted in 2003 showed

that in March alone, British

opinion of the United States fell by 27% from the previous summer

to 48% favorable opinion rating. (Pew also reports that British opinion

has shifted back up with

the success of the military campaign.)

The BBC has also fallen into the pitfalls of 24 hour news coverage.

The BBC had been plagued with significant factual errors in their

reporting

which

embarrassingly

had to be retracted on air. One of the most glaring was the reporting

of the large scale Basra uprising on March 25th in British controlled

territory.

First,

it was confirmed by a British military spokesman, than later

retracted by Tony Blair as to the 'belief that there was a limited uprising of some sort.' Another

story involved the US taking of Umm Qasr, Iraq's port in the south. BBC

also reported on March 21 as to the unconfirmed US control of the port. In a

volley of claims and counter-claims, the port apparently had been taken 'nine

times' according to military sources. In a March 28th interview, the BBC

network chiefs were quick to assess the problem as that of relying too heavily

on the statements coming out of military sources, calling it one of the worst 'misinformation' campaigns.

Mainstream American journalists seemed less troubled with the loss

of objectivity. As Bob Schieffer, a CBS evening anchor, stated

at a speech

at the RTNDA (Radio-Television

News Directors Association & Foundation) that 'he had never been more

proud to call himself a journalist at the coverage of the embedded reporters.'(Cochran)

The very part of society that was insured constitutional protection

of free speech so as to act as guardians against the tyranny

of the government over its citizens

has lost its civic value.

Al-Jazeera's reporting differs in its focus, but purports the same message -

Resistance is futile. Al-Jazeera calls itself the 'Arab CNN', combining elements

of the live broadcast, call in programming, interviews, and independent footage.

During the US lead war, they focused on showing montage photos of the victims

and of the dead. This message of victimology is no more humanizing than the

message sent by American television. Showing an image of a child with his head

blown up respects neither the dead nor the living. It is contrived to fit the

narrative of the oppressed tribal man. Repeating visceral images of the dead

spliced with text and other images creates even more of a disjuncture - one

side representing impotent savagery and the other representing a powerful mix

of the suit and the military. The implied image feeds into its own stereotype

- the West as powerful and modern, and the Middle East in a state of chaos and

disintegration. It re-affirms the relative positions in the power structure

through media representation.

Media analyst, Michael Wolff, argues that Al-Jazeera is all about television

ratings, not propaganda. He refers to the grittiness of the film and the panning

effect of the dead as qualities embodying that of a snuff film. Al-Jazeera does

porn, but not in the way Americans can, instead it is rather a low budget spectacle.

What it lacks in good narrative structure, it makes up in blood and guts, and

lots of it. The chaotic and unfiltered news out of Al-Jazeera embodies the qualities

that make tabloids so readable and digestible.

The oddity of the Al-Jazeera phenomenon is the American-ness

of it all. Underneath it all, Al-Jazeera television is a

commercial entity.

Its

main goal is to

keep its some 35 million eyeballs glued to the television

sets for the eventual advertising

payoff. The tricks that it employs have less to do with some

different Arabic way of viewing life, but more to do with

shock TV- from combative

guests

on Faisal al Qasim to the 'ambulance' chasing

style of street reporting. They have taken the quantum leap

over the staid media channels like the BBC, and thrust

themselves fully into the role of future media conglomerate.

Even the Emir of Qatar, who has funding the media station,

knows that oil is a dwindling commodity.

This is the type of media that Edward Said himself would

criticize. In Covering Islam, Said details a subtle and profound

argument

calling for

intellectual

responsibility in the face of a monolithic version of 'Islam' in

the mainstream Western press. Al-Jazeera returns the favor

with its own monolithic version of

the West. In a recent Al-Jazeera poll, 74% of respondents

believe that the Iraqi invasion is a war to create a new

American world order, and over 88% of respondents

believe that it was a war created for the benefit of Israel.

In this war effort, Al-Jazeera is clearly a winner. Not only

did it become one of the most viewed websites in Europe,

but in the midst

of the war

in April,

it also became Lycos top search term. In an interview

with Al-Jazeera's

marketing and PR head, Jihad Ali Ballout, Ballout explains that the business

plan of Al-Jazeera is to 'dominate the region, and then with English language

broadcasts and other international partnerships, extend the brand throughout

the world.' (Wolff) It is Arabic based, but not rejectionist. Al-Jazeera

does not represent a version of Benjamin Barber's

Jihad vs. McWorld, but rather, McJihad competing against

McWorld.

So what needs to be done? This question begs at the larger

issue of what is in America's interests. Perhaps

there is political propaganda on the commercial network

news, but we seem to care little about the more constant

economic propaganda

in the media. If commercial television is strictly

about entertainment,

perhaps mainstream journalists should come on the

air with a disclaimer: What

you are about to see is only fiction and intended

for consuming audiences, please prevent young impressionable

minds who believe in civic responsibility to view

the following programming . Part

of the problem lies in the reporter's

proposition that s/he is objective. It is clear

that all the process of filing a new story is subjective

and value-laden. The more journalists reveal the 'grey' areas

of their story, the contradictions in the story,

and the lack of knowledge over whom is wrong

or right, the more honest and informative news

stories will

become.

Although CNN and FOX are imminently popular,

this has not prevented media critics and

scholars to purpose

a

more didactic

form of

television programming

as an

alternative to 'shock and awe' broadcasting.

The public is currently funding PBS and C-SPAN

through a consortium of cable operators. Unfortunately,

neither channel garners a large public viewership.

While they are content driven, they are not visually

driven and audiences seem to prefer the jazzier

infotainment

of CNN and FOX.

Americans may prefer blissful ignorance; however,

the rest of the world seethes in the hypocrisy

of the arrogant

empire

preaching

democratic

values. If 9-11

is not one wake-up call about the impossibility

of isolation in a globalized

community, then American will suffer from more

of the same. We will know less about our leaders and

government,

if the

press

does not

hold them

accountable for their policy actions. Democracies

are demanding taskmasters, mostly because the require much of their

citizens to

participate

and become

informed. Instead

of mindlessly

viewing the

press from the narrow channels of corporate media,

citizens can use alternatives such as internet

receive more in-depth

analysis

and

hear dissenting voices.

As the growth of internet can attest, the American

public has been quick to look

for information elsewhere.

While television has been co-opted by large corporations,

this does not have to be a static fact. The

public airwaves are owned

by the

public,

and licensed

to cable and commercial broadcasting networks.

The public can dictate better terms for themselves

with non-commercial

programming

choices.

Corporations can be better regulated as to

the share of cross-ownership in media properties

to

prevent further homogenization of the press,

as well as to prevent the further

concentration in control of the public airwaves. If

television is a socializing agent, we

can use the medium to learn how others in

the world view

the United

States.

The

public can

demand

funding

for the public broadcasting of alternative

international public networks such as the

BBC, CBC (Canadian

Broadcasting),

and France

2 to create a better democratic society with

a more informed citizenry.

Bibliography

Adoni, Hanna, and Sherrill Mane. 'Media and the Social Construction

of Reality.' Communication Research. 11 (1984): 323-40.

Andersen, Robin. Consumer Culture and TV Programming. Boulder: Westview

Press, 1995.

Bagdikian, Ben. Media Monopoly. Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.

Barber, Benjamin R. Jihad vs. McWorld. New York: Ballentine Books, 1996.

Barker, Chris. Television, Globalization and Cultural Identities. Philadelphia:

Open University Press, 1999.

Berger, Arthur Asa. Manufacturing Desire: Media, Popular Culture, and

Everyday Life. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1996.

Bremer, L. Paul. 'Terrorism, the Media, and the Government.' Newsmen

and National Defense: Is Conflict Inevitable? Ed. Lloyd J. Matthews. McLean:

Brassey's, 1991. 73-80.

Brockes, Emma. 'War Porn.' The Guardian, April 11, 2003.<http://media.guardian.co.uk> (23

July 2003).

Bruck, Peter and Colleen Roach. 'The News Media and the Promotion of

Peace.' Communication and Culture in War and Peace. Ed. Colleen

Roach. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1993. 71-97.

Chomsky, Noam. Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies.

Boston: South End Press, 1989.

Cochran, Barbara. 'CBS' Bob Schieffer Accepts Paul White Award

At RTNDA@NAB.' < http://www.rtnda.org/news/2003/040803a.shtml> (23

July 2003).

Crandall, Jordan. 'Unmanned: Embedded Reporters, Predator Drones and

Armed Perception.' July 23, 2003. <http://www.ctheory.net/.>

Demers, David. Global Media: Menace or Messiah? Cresskill: Hampton Press.

1999.

'

Extra!, Special Gulf War Issue 1991' Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

2003 <http://www.fair.org/extra/best-of-extra/gulf-warlwatch-tv>

First Amendment Forum. Speech by Todd Gitlin, author of Media Unlimited:

How the Torrent of Images and Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives. 2003 <http://www.columbia.edu/cu/news/vforum/03/firstamendmentforum/

Hartley, John. The Politics of Pictures: The creation of the public in

the age of popular media. London: Routledge, 1992.

Kampfner, John. 'Saving Private Lynch story 'flawed.'' BBC

News, May 15, 2003. <http://news.bbc.co.uk> (4 August 2003).

Kappeler, Susanne. The Pornography of Representation. Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Kellner, Douglas. Media Spectacle. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Kelly, Jim and Bill Elliott. 'Synthetic History and Subjective Reality:

The Impact of Oliver Stone's Film, JFK.' It's Showtime!

: Media, Politics, and Popular Culture. Ed.

David A. Schultz. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2000. 171-196.

Kitzinger, Jenny. 'A sociology of media power: key issues in audience

reception research.' Message Received Glasgow Media Group Research

1993-1998. New York: Addison Wesley Longman, 1999. 3-20.

'

Lamis Andoni on Al Jazira' Interview with Peter Hart. Counterspin Archives.

2003. 2 Dec 2002 <http://archive.webactive.com/webactive/cspin>

Larson, Stephanie Greco. 'Political Cynicism and Its Contradictions

in the Public, News, and Entertainment.' It's Showtime! :

Media, Politics, and Popular Culture. Ed. David A. Schultz. New York:

Peter Lang

Publishing, 2000. 101-116.

Lawson, Annie and Lisa O'Carroll and et. 'War Watch: Claims and

counter claims made during the media war over Iraq.' The Guardian,

March 30, 2003. <http://media.guardian.co.uk> (23 July 2003).

'Learning from the Last War: The media and the military. The next war:

Where will we go from here?' Goldensen University Satellite Seminar

Series. 2003. 16 Nov 2000.

Lewis, Justin. 'Biased Broadcasting Corporation.' The Guardian,

July 4, 2003. <http://www. guardian.co.uk> (4 August 2003).

Litterest, Judith K. Affective Framing of Crisis: Broadcaster Nonverbal

Communication During the 24 Hours Following the Attack on America. St.

Cloud State University.

30 June 2003 <http://web.stcloudstate.edu/jklitterst/September%2011th%20Paper%20Draft.htm>

Miller, David and Greg Philo. 'The effective media.' Message

Received Glasgow Media Group Research 1993-1998. New York: Addison Wesley

Longman, 1999. 21-32.

Pew Research Center. 'Pew Global Attitudes Project: Views from a Changing

World.' <http://people-press.org> (23 July 2003).

Phelan, John M. Disenchantment: Meaning and Morality in the Media. New

York: Communication Arts Books, 1980.

Philo, Greg. 'Conclusions on media audiences and message reception.' Message

Received Glasgow Media Group Research 1993-1998. New York: Addison Wesley

Longman, 1999. 282-289.

Roach, Colleen. 'Information and Culture in War and Peace: Overview.' Communication

and Culture in War and Peace. Ed. Colleen Roach. Newbury Park: Sage Publications,

1993. 1-40.

Rusher, William A. 'The Media and Future Interventions: Scenario.' Newsmen

and National Defense: Is Conflict Inevitable? Ed. Lloyd J. Matthews. McLean:

Brassey's, 1991. 111-120.

Rushkoff, Douglas. Coercion: Why We Listen to What 'They' Say.

New York: Riverhead Books, 1999.

Said, Edward. Covering Islam. New York: Random House Publishing, 1992.

Sarkesian, Sam C. 'Soldiers, Scholars, and the Media.' Newsmen

and National Defense: Is Conflict Inevitable? Ed. Lloyd J. Matthews. McLean:

Brassey's, 1991. 61-72.

Schultz, David. 'The Cultural Contradictions of the American Media.' It's

Showtime! : Media, Politics, and Popular Culture. Ed. David A. Schultz.

New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2000. 13-28.

Shah, Anup. 'Media in the United States.' Global Issues, April

10, 2003. <http://www.globalissues.org/humanrights/media/usa.asp> (23

July 2003).

Streich, Gregory W. 'Mass Media, Citizenship, and Democracy.' It's

Showtime! : Media, Politics, and Popular Culture. Ed. David A. Schultz.

New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2000. 51-72.

Shapiro, M.A. and A. Lang. 'Making Television Reality: Unconscious

Processes in the Construction of Social Reality.' Communication

Research. 18 (1988): 685-705.

Trainor, Bernard E. 'The Military and the Media: A Troubled Embrace.' Newsmen

and National Defense: Is Conflict Inevitable? Ed. Lloyd J. Matthews. McLean:

Brassey's, 1991. 121-130.

Walker, Simon. 'US Marine from the 15 Marine Expeditionary Unit' 23

Mar 2003. Online image. AP Photo. 18 July 2003. <http://galleries.news24.co.za/iraq/Weekend01>

Willey, Barry E. 'Military-Media Relations Come of Age.' Newsmen

and National Defense: Is Conflict Inevitable? Ed. Lloyd J. Matthews. McLean:

Brassey's, 1991. 81-90.

Wolff, Michael. 'Winners in the war.' The Guardian, April 21,

2003. <http://media.guardian.co.uk> (23 July 2003).

Young, Jen. "Al-Jazeera the most sought after internet searches." <http://www.lisnews.com/article.php3?sid=20030402122013> (13

April 2003).