A Call to Arms: A Comparison of the Semiotics

of the Peking Revolutionary Opera and 9/11 Media Images

“Hence

we know that the leader of the army is in charge of the lives of the people

and the safety of the nation.” (Tzu 65)

Since the World Trade

Center attack, the American government has used the media to induce the people

into supporting its military actions. In the initial stages, images of the

World Trade Center towers burning and collapsing filled our television screens

and haunted our dreams. America watched hours of uninterrupted repetitions

of chaos, rescues and death. Photos of our attackers covered every screen

from television to computer. The loss of the towers damaged America economically

as well. Thousands of jobs and lives lay lost in the rubble. With the loss

of a major financial center that housed many businesses, the nation’s

economy suffered a severe hit, which will take years to repair. Upon seeing

these events, our nation united in purpose and prepared for war. A damaged

nation cried for retaliation and retribution.

During the anthrax and

biological weapons scares, an already tentative public became more fearful.

News reports covering the deaths of those contaminated and analyses of the

anthrax bacteria created a sense of fear for many Americans. Some people became

afraid of opening their mail without wearing gloves. Internet and mail orders

decreased as numerous consumers imagined anthrax laced packages arriving at

their front doors. People opted to stay home instead of patronizing restaurants,

stores and other public areas for fear of anthrax. The economy, already in

a recession and reeling from the attack on September 11th, further weakened.

The government’s tactics created more fear and furthered the recession.

Their propaganda of choice was not the best for maintaining McWorld’s

support during this war. They would have been better served with persuasive

tactics with overt visual messages akin to those of the Peking Revolutionary

Opera. A society of visually oriented consumers deserves, better yet requires,

visually oriented consumer based propaganda. Commercials, billboards and magazine

advertisements with celebrity endorsements with tie-in items such as clothing

and toys would feed into this mindless consumerism we call McWorld. I am suggesting

that we have McWorld create McWar.

McWorld is the consumer

society in which we live. Within its confines, the consumer has many choices.

One would think the consumer have a choice whether to buy or not, but in actuality,

McWorld only asks the consumer which item they’d like to purchase. McWorld’s

sole purpose is creating profits. Usually, this goal is reached by monopolies,

which Barber defines as “a polite word for uniformity and virtual censorship

but as a consequence of … the quest for a single product that can be

sold to every living soul.” (Barber 137-138) Typically, they sell the

same product to every living creature, in hopes of increasing their financial

standing without regard for the homogenous society this generates.

McWorld’s hold over

the American public is cemented by the images it generates. As we have moved

from oral to visual cues its power has increased dramatically. Over the last

century, as our forms of communication became more visual, news and advertising

have risen in standing and changed our perceptions of the world. We once transmitted

news orally until printing became inexpensive enough to generate newspapers

and books for the masses. With the invention of the photographs, words could

hardly compete with the perceived truth of the scenes they captured.

“The

new imagery, with photography at its forefront, did not merely function

as a supplement to language, but bid to replace it as our dominant

means for construing, understanding, and testing reality.” (Postman

74)

Pictures served not to

enhance but replace our use of words to understand our environment and its

messages. With the invention of television, we moved further from using words

to understand our surroundings. Since television processes images and information

faster than human emotions can handle, our society became inundated and overloaded

with images. Consequently, we have become increasingly visually oriented –

preferring pictures to word – and increasingly susceptible to images

in the news and advertisements. Hence, the link between McWorld and the consumer

mind solidifies.

Each image we see, whether

positive or negative, affects us. According to studies by Reeves and Naas,

experiences before a negative event are not remembered as well as events following.

Therefore, events prior to the planes crashing into the towers on September

11 would not have the same weight in our minds as those events following.

We essentially discard the less violent images. Viewing violent scenes arouses

our senses. The intensity of the event is maintained with each replay. The

increased level of arousal caused makes people “flee better, fight harder

or act more quickly”. In the Reeves and Naas study, when people viewed

gory images in the news, they remembered visual images, not spoken words.

Their arousal levels increased and ideas of retaliation seemed reasonable

and immediately necessary.

The news media is fully

aware of the effect of their actions. They count on the fact that “[television’s]

rapid-fire images help to create a[n]…atmosphere that puts viewers into

high-alpha dreamlike state that blocks out almost all thought.”(Roach

11). They knew if we witnessed the repeated destruction of the towers and

we would almost blindly rally behind the government’s cry for retaliation.

Simply put - manipulation of the masses gets dressed up as public information.

Within the week following the attacks, the American public, whipped into an

emotional frenzy, was in support of military action.

This contrasts with the

approach of Mao Tse Tung. He gained the support of the masses presented military

actions beautifully, almost surgically, through the theater. During the Japanese

occupation, China needed unification physically and ideologically, to support

a potentially long military campaign. For this reason, Mao began the “reportage

plays” in 1931. They were used to “arouse patriotism against a foreign

aggressor and enemy”. Traveling theater companies performed plays in

villages across China spreading patriotic messages to the largely poor and

illiterate masses. As television was not a luxury the average citizen could

afford, the plays could reach everyone.Mackerras finds this approach “highly

practical and utilitarian…[Mao] was dealing with a numerically gigantic

people steeped in tradition whom he planned to haul towards progress.”(149)

They allowed Mao to reach a large group with the same message and touch them

in a way words could not. Also, by making military action a part of entertainment,

the reality of war seemed less daunting. The public was soothed into accepting

war as a part of life through the theater. Like television, the plays were

“direct, to the point and easy to understand.”(Mackerass 154)

Mao believed art and politics

had to be united to bring political ideologies to all classes. During the

talks at Yanan in 1942, he said, “There is in fact no such thing as art

for arts sake, art that stands above classes or art that is detached from

or independent of politics.”(Melvin D1) This belief fueled the creation

of the PRO to solidify the government’s hold on the Chinese people and

renew their patriotism and fervor for military action. Mao’s wife, Madame

Mao, devised an option to guarantee a captive audience ripe for ideological

inundation. She banned all performing arts and other operas during the Cultural

Revolution, from 1966-1976. She then filled every opera with anesthetized

propaganda. Ballerinas, en pointe toting machine guns triumphed over evil

repeatedly – all the while smiling as if war were the proverbial “piece

of cake.” However, as in all propagandist campaigns, eventually, the

rhetoric wore thin and the public support waned. We have seen a similar situation

in post-attack America as the semiotics and propaganda used by the American

government have negative effects on the nation.

Semiotics is the study

of socially accepted meanings of signs and symbols. These signs and symbols

help us understand our reality. They shape our perceptions. They can include

words, slogans, pictures, gestures, traffic signs, dress codes and colors.

Even lighting and angles of camera shots send us certain signals. For example,

we believe a person wearing a suit and tie to be formally dressed as society

calls that particular clothing combination formal. This sign evolves into

a myth if the suit has a brand name on the label such as “Armani”

which is associated with thoughts of expense and luxury. The idea of luxury

now overpowers the original meaning of the suit. Signs become myths when their

attached social and political connotations overtake their denotations (Bignell

22). The distorted meaning creates the illusion of an undeniably true message

that can only be read one way instead of it being one possibility. The presented

truths appear to be natural, almost common sense. All socio-political groups

propagate myths. They are effective politically as they help perpetuate ideologies,

or perceptions of reality and society followed by a group, which assume apparent

truth of some ideas and bias of others. Ideologies change with societies’

economic and political powers. Myths help ideologies giving them a natural

appearance. Both are communicated to the public, either overtly as in China

or covertly in post-attack America, through propaganda.

Propaganda is communication

with the intent of swaying opinion, whether overtly or covertly, to support

an ideology. “The Way means inducing the people to have the same aim

as leadership, so they will share death and share life without fear or danger.”

(Tzu 43) But before the public complies with propaganda, there must be motivation

(Sandor 129) most effectively created by “individual compliance”(quoted

Sandor 129) or behaviors people are persuaded or otherwise prevailed upon

to perform. “Public participation creates popular support which is always

important to the outcome of war.”(Sandor 128) According to Abby Sandor,

two key elements create this participation: symbolic displays of support for

government ideology and widespread use of audience inclusive rhetoric in public

communication (129). Both the media since September 11 and the Peking Revolutionary

Opera (PRO) use induced compliance through public participation. In America,

since September 11, the flag pins, flags in commercials and other broadcasts

and slick slogans characterizing each phase of the initial destruction, potential

chemical warfare and war offer ample opportunities for public participation.

In China, images of the red sun, the Chinese flag, slogans and banners and

propaganda-filled operas created public participation.

“Propaganda has always

been a part of war.”(Hiebert 318) Though tactics have evolved, this idea

remains true. In Communist China, the PRO presented the propaganda through

the theater. Since September 11, images of patriotism, destruction and new

heroes have covered the news media and advertisements. The government recognized

the public’s need for retribution and used controlled images and other

visual cues to heighten those to control the people.

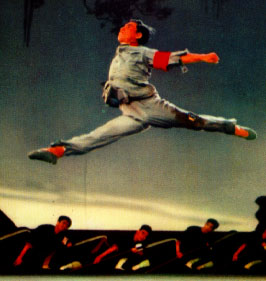

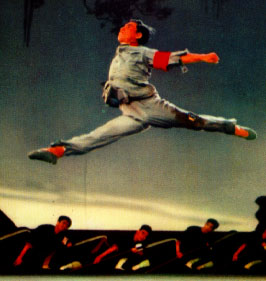

The Peking Revolutionary

Opera is a form of non-illusionist theater filled with repeated violent images

of communists winning every battle. Non-illusionist theater is most effective

with homogeneous audiences who comprehend the meanings of the theater’s

semiotics. In all kinds of theater, there are various visual elements usually

agreed upon and understood within a particular culture that affect how events

are deciphered. Characters, lighting, colors, symbols, and printed slogans

are among them.

The Peking Revolutionary

Opera broke away from traditional Chinese visual signs and symbols in order

to appeal to the greater population while feeding them Maoist ideology. Characters

were the most important part of the plays. Madame Mao believed,

“We must

work hard to create worker/peasant/soldier heroic characters. That

is the basic task of socialist literature and art. Only with this

type of mode and with successful experience in this area will we

be persuasive, able to consolidate our hold on this front.”

(Mackerass 150)

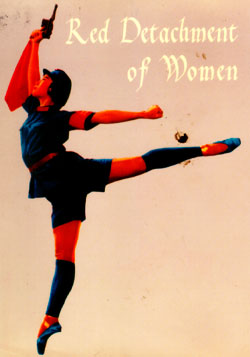

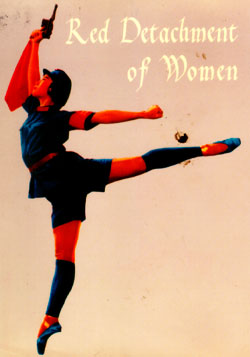

Certain roles, known as

the three prominences, were crucial to the operas. Positive, heroic, and main

heroic characters received the most important positions. Main heroic characters

held almost superhuman status. They carried the drama’s meaning. Both

“positive and heroic characters were generally portrayed without any

human blemishes.”(Tubingen 102) Positive characters stand tall and straight

while negative ones slouch. Ballerinas standing en pointe with machine guns

in their hands flitted across the stage. They represented strong heroic women

fighting for their rights. Negative characters brought other elements to the

operas. Negative characters were always the enemies – usually Japanese

or Nationalist spies. They created the conflict, which the positive characters

resolved to defeat them and end each play on a triumphant note.

In the American news media,

characters also exist. Heroes are born in tragedies such as the September

11th attack. Aldous Huxley says in the Brave New World :

“Where

there are wars, where there are divided allegiances, where there

are temptations to be resisted, objects of love to be fought for

and defended – there, obviously, nobility and heroism have

some sense. “ (237)

As the photos of lost

firemen and policemen continued to pour in with television interviews of survivors

and family members of the deceased, America redefined the meaning of hero.

Policemen, firemen and emergency medical services personnel became recognizable

as our symbol of courage and strength. Their uniform was their costume. I

have witnessed people applauding firefighters and police personnel on the

street since the attack. Many local restaurants offered free meals or other

discounts to the new heroes. And as in the PRO, our heroes appear superhuman.

By surviving the September 11 attack and working extended shifts to recover

any remaining bodies, they increased their standing in the eyes of the public.

News reporters present

another type of character important to note in the analysis of post-attack

America. Their style of dress is typically formal. “Men wear suits and

women wear business clothes…News presenters are thus coded as professional,

serious, and authoritative.” (Bignell 113) The chosen style is to portray

their seriousness about delivering the news objectively and professionally.

Jonathan Bignell reports that these meanings are further supported by the

impersonal language and lack of gestures used by newscasters. “They cultivate

a smooth delivery and try to convey an impression of detachment that places

them above the rough and tumble of their subject matter.” (Parenti 122).

They want us to trust them. In White Noise, Don Delillo best describes the

feeling reporters attempt to evoke:

“The reporter…spoke

clearly and strongly and yet with some degree of intimacy, conveying

a sense of frequent contact with his audience, of shared interests

and mutual trust….He made it sound like a lover’s promise.

“ (222)

Immediately following

the attack, some journalists wore American flag pins on the air. “Open

displays of patriotism go against traditional US journalistic standards of

maintaining visible neutrality or objectivity when covering a story”(Jensen

A28) This breech of accepted standards clued the public in to the seriousness

of the attack. The lighting of an image or staged production gives other signs

to the viewer.

In the PRO, lighting usually

indicated the character’s disposition. Positive characters have scenes

in bright lights to signify daytime. Negative characters are more active at

night or in shadows or caves – in dimmer light. If negative and positive

characters exist on the stage simultaneously, the positive characters have

the spotlight on them.

In news media and advertising,

lighting plays a significant role in our understanding of events. Tom O’Dell,

Strategic Planner at a pharmaceutical marketing company, says that in most

advertisements and programs, darker lighting implies a negative element, disease,

dirt, etc. Brighter light usually directs our attention to the solution, the

product being sold.

Colors used in the model

operas offered great character insight. Bright colored costumes and props

were reserved for positive characters. They often dressed in the clothing

of the working class – giving the viewer a hero with which they could

identify. Bright green and an extremely bright red hues represent “flourishing

vegetation of late spring and summer,” (Drama 124) and are only used

on positive characters. Red also signifies courage, loyalty, fire and the

political ideology of Maoism. Red flags with communist slogans stood in back

of many scenes. Negative characters, such as bandits, never wore red. Bandits

could wear somber, earthy hues such as: dark green, dark blue and black. The

media uses colors similarly.

In the media, colors have

certain meanings. Black and white or monochrome images can symbolize reality

(as in a newspaper) or a negative situation if juxtaposed with a color image.

Red creates alarm and panic. People think of blood and sirens when they see

red – things that are often cause for alarm. Bignell says, some shades

of blues, green and gray are typically seen as cold and uncomfortable as in

police dramas. But, other shades of blue and green can be calming and bring

tranquility to the viewer. Deeper shades can be associated with nature or

water. White symbolizes purity. In the past, Cover Girl magazine used white

in on all their covers to portray a clean image. Yellow and brown usually

connote warmth and comfort. According to Tom O’Dell, yellow brings happiness

and the sun to mind. Most people equate it with good feelings.

In the PRO, the sun figured

prominently in most operas. It is a traditional and positive symbol. It is

the “hegemonic symbol for yang, the source of all brightness and light

in the universe [and] a designation for the emperor.”(Drama 126) In the

1950’s, it became representative of Mao and Maoism. It also signified

the element fire. Fire is “the anger and passion of the oppressed classes

and their fervent desire for revenge.”(Drama 127) Fire is ascendant which

calls to mind positive characters, enlightenment or spiritual liberation.

Oppression by bandits is shown through ice and water. Pine trees are symbols

of ascendancy and moral rectitude. Thin weak trees are descendant. Mountains

are also ascendant and sacred.

The most sacred symbol

since the attack has been the American flag. Within days after the events

of Sept. 11, many citizens had flags outside their homes, on their lapels

and their cars to show their support of America. Numerous offices and restaurants

have flags hanging from doors and windows. Many advertisements have patriotic

ribbons and images of flags in or behind corporate logs or replacing them

altogether for a short period. These flags give the public an opportunity

for public participation. In the Gulf War, the wearing or display of the yellow

ribbon showed public participation. It symbolized support for the soldiers,

not the war. The ribbons and the flags serve the same purpose, to unite the

American public.

“We have become a

nation unable to think except by meals of slogans.” (Berman 54) In Media

Semiotics, Jonathan Bignell states that the title sequence, or slogan, “establishes

the mythic status of news as significant and authoritative, while simultaneously

giving each channel’s news programmes a recognizable ‘brand image’

which differentiates it from its competitors.”(Bignell 116) For September

11 and the days following, most networks created variations of the title:

America under Attack. The other popular choice was Attack on America. Always

3 lines of text arranged vertically, usually with America on top – as

the victor. The first few days there were dark colors and even dark lighting

on the slogans. As we assessed the damage and started the recovery efforts,

the colors changed to blue, red, and white – symbolizing triumph. The

words spoken in the PRO were continuous streams of propagandist slogans and

ideas. Communist slogans faced the audience throughout the play.

Slogans are key elements

in advertisements. It’s the line you remember after seeing the ad. Many

of us remember “Just do it,” Nike’s popular ad campaign. Others

may know “Where’s the beef?” Wendy’s ad campaign from

the early 1990’s. In any case, most people know at least one ad slogan.

In an advertisement, life is repackaged and sold to us from a new angle. Everything

from the mundane to the conceptual can be sold to the public through an advertisement.

Household bleach gains a personality, perhaps even speaks. Fabric softener

has talking teddy bears telling us about its goodness but showing us the softness

and fluffiness of the bear as if to imply the product did it. The Army sells

us on the concept of being “all that we can be”, we buy into it

and enrollment increases.

News media and advertising

offer particularly effective forms of propaganda. In America, we believe the

news media offers us an objective view of situations and events. However,

that is not the case. Being integral parts of McWorld, their goal is to create

profits. All of the visual elements are used to catch and entertain us long

enough for us to buy the magazine or watch the show in order to increase profits

from advertising. Television news, newspapers and news magazine profit from

advertisements. Advertisers expect consumers to stay tuned long enough to

see or read about their product or service. If the news is not interesting

enough, we don’t watch it and consequently, we miss the ads. Therefore

the news can never be truly unbiased or completely revealing. It is always

linked to the need for advertising dollars.

“TV

stations that concentrate most on violent and sensational news get

the highest ratings and, thus, the highest profits. Wars, too, always

make a lot of money for the mass media.” (Hiebert 12)

We receive news but we

only receive those pieces of information that the media deems acceptable for

our consumption. “News is no longer the information that people need;

it is now the information that news executives believe that people want.”

(Hiebert 12) This is especially true during war when public support is most

needed by the government. Immediately following the attack on America, Condoleeza

Rice, sent message to all stations asking them to submit images to her prior

to airing them. The Army and Marines use ads to boost recruiting. Dairy farmers

employ it to sell us on the idea of drinking milk and eating cheese. The government

currently uses Charlotte Beers, an advertising executive, to create propagandist

advertisements for the Middle East in an effort to convince them to like Americans.

Tom O’Dell, Strategic

Planner equates advertising with propaganda. He uses focus groups to gauge

feelings and opinions on products to help manufacturers choose the perfect

logo and the most effective advertisements to win consumer’s dollars.

In essence, he is the ear of McWorld. He hears our needs, communicates them

to companies and helps them sell us as much as our wallets can handle.

The American government

would benefit from using some of the PRO’s approach to propaganda. America,

land of consumers, requires a propaganda campaign more in line with its way

of thinking.

McWorld sells us products

through celebrity endorsements. War can be packaged similarly. Imagine, Britney

Spears in fatigues drinking a glass of milk. The caption reads: Got War? It

continues with a few catchy lines on the benefits of war and how we should

support our government. Did I mention that Britney is wearing a designer outfit

of fatigues with matching accessories? Also, the Britney fatigue dolls look

amazingly like her. All are on sale at a Kmart near you.

Not only does this tactic

grab the attention of a young reader, it brings a new, lighter element to

war. Which is necessary to continue propaganda over a long period of time

as in Communist China. The celebrity should change periodically to draw in

a new crowd of believers.

The second tactic would

be to pick one or even several particularly stunning, military personnel,

police or firefighters and use them in advertisements. Create a calendar of

the sexiest firemen or women. Use the chosen police persons in pro-war ads.

Picture a military person in fatigues holding a machine gun, the tag line

reads “This is war. This is your country at war. Any questions?”

Using the elements of

McWorld, celebrity endorsements, clothing and toy tie ins and advertisements

can create a more effective, innocuous campaign. This allows the citizen to

view war as a part of everyday life, not a tragic event to be feared. It anesthetizes

war for the public.

Also, it can bring revenue

for the government whose current tactics are “creating a sense of panic

that [run] counter to efforts to get Americans to resume their normal lives.”

(Mitchell, A14) The clothing and toy lines can generate profits for the store

selling them and the government. Why think about shooting when you can think

about shopping?

Works

Cited

Alley, Rewi. Peking Opera. Beijing: New World Press, 1984.

Bagdikian, Ben. ”The

Empire Strikes.” Hiebert 147-151.

Barber, Benjamin. Jihad

vs. McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism are Reshaping the World. New York:

Ballantine Books, 1996.

Berkman, Dave. ”The

Totalitarianism of Democratic Mass Media.” Hiebert 102-104.

Berman, Morris. The Twilight

of American Culture. NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000.

Bignell, Jonathan. Media

Semiotics: An Introduction. Oxford: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Carlson, Margaret. ”Can

Charlotte Beers Sell Uncle Sam?” Time.com 14 Nov. 2001

DeLillo, Don. White Noise.

New York: Viking Press, 1986.

Denton, Kirk. “Model

Drama as Myth: A Semiotic Analysis of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.”

Ed. Tung and MacKerras. 119-136.

Hiebert, Ray Eldon. “The

Growing Power of Mass Media.” Hiebert 3-15.

Hiebert, Ray Eldon. “Mass

Media as Weapons of Modern Warfare.” Impact of Mass Media: Current Issues,

4th Edition. Ed. Ray Eldon Hiebert. New York, Longman. 317-326.

James, Caryn. “Live

Images Make Viewers Witnesses to Horror.” New York Times. 12 Sept. 2001:

A25.

Jensen, Elizabeth. “After

the Attack: TV Execs Debate On-Air Flag Displays.” New York Times. 20

Sept. 2001: A28.

Judd, Ellen. “Prescriptive

Dramatic Theory of the Cultural Revolution.” Ed. Tung and MacKerras 94-118.

Kernan, Alvin. In Plato’s

Cave. CT: Yale University Press, 1999

Knight, Al. “Mass

Media Should Slow Down.” Denver Post. 16 Sept. 2001: E05.

Mackerass, Colin. “Theater

and the Masses.” Chinese Theater: From Its Origin to the Present Day.

Ed. Colin Mackerass. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983. 145-183.

Melvin, Sheila. “On

Golden Anniversary, A Leaden Yoke of Ideology.” New York Times. 26 Sept.

1999: D1.

Mitchell, Alison. “White

House Issues Alert of New Terrorism Threat.” New York Times. 4 Dec. 2001:

A13

Parenti, Michael. “Methods

of Media Manipulation.” Hiebert 120-124.

Platt, Larry. “Armageddon

– Live at 6!” Hiebert 242-246.

Reeves, Byron and Clifford

Naas. The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television and New Media

like Real People and Places. CA: CSLI , 1996.

Roach, Colleen. “Informative

and Culture in War and Peace: Overview.” Communication and Culture in

War and Peace. Ed. Colleen Roach. CA: Sage Publications, 1993.

Sandor, Abby. “Participatory

Propaganda in the Gulf War.” Propaganda Without Propagandists: Six Case

Studies in U.S. Propaganda. Ed. James Shannahan. NJ: Hampton Press, 2001.

127-140.

Shales, Tom. “TV

Once Again Unites the World in Grief.” Hiebert 60-66.

Tomaselli, Kenyan. Appropriating

Images: The Semiotics of Visual Representation. Denmark: Intervention Press,

1996.

Turbinger, Gunter Narr

Verlag. The Semiotics of Theater. Trans. Jeremy Gaines and Doris L. Jones.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Tung, Constantine and

Colin MacKerras. Drama in the People’s Republic of China. Albany: State

University of New York Press, 1987.

Tzu, Sun. The Art of War.

Trans. Thomas Clearly. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1988.