CYBERPERFORMANCE I:

Humans and Nature

Professor Julia"Evergreen"Keefer, NYU

(All photos courtesy of Victor Hinojosa)

If you happened to be wandering around New York

University's Academic Computing Facility on Saturday morning, 2 May 1998,

you would have come across a cyberperformance:

For four hours, from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. performers, computers, students,

faculty, shamans and children intermingled in a dramatic intersection of meatspace,

cyberspace and deepspace.

For four hours, from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. performers, computers, students,

faculty, shamans and children intermingled in a dramatic intersection of meatspace,

cyberspace and deepspace.

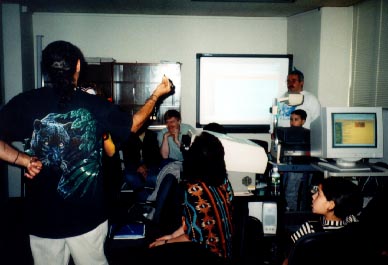

Professor Keefer's Humans and Nature class was theoretically doing a multi-media presentation of their webfolios and research for the semester. But instead of doing a multi-media presentation, Keefer wanted to turn the event into a cyberperformance.

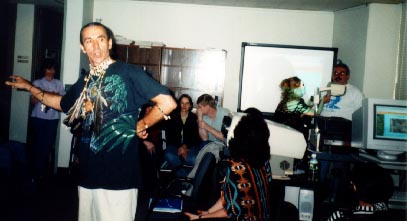

Room 313 is set up for multi-media presentations

with three computers, two projection screens, and the Smart Board, a hyperactive

whiteboard that allows oneto draw, make notes and surf the net at the same

time, or even "surf the net by foot control" as Professor Keefer

is doing in this photo.

The room was small but big enough for 3 screens and computers, a Smart Board and a blackboard and about 30 chairs, a table and the bear rug and props.

Seating was multi-level from the floor to chairs to tables to a low ceiling where Professor Keefer, dressed up as an endangered species, banged her head in an effort to stop the spontaneous "real" fight between the computer guru and the Puerto Rican rainforest shaman. But let's start from the beginning.

The performers were Writing Workshop II students, multi-cultural and multi-disciplinary, with no training as performers. Some had never even seen live theatre. Props consisted of a wigwam of fur and leather, a pumpkin, an Eskimo doll, masks, bear rugs, pottery, tea and cups, incense, and herbs to burn, all of which looked incongruous in this sterile electronic cave which blocked out the daylight and street reality with heavy Venetian blinds.

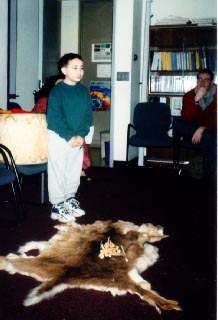

Computer guru Michael Harkins brought his son

Matthew to perform the "Jabberwocky" as a symbol of children's facility

with the new language.

Nadine Murray brought her two young boys who immediately began to play with masks and follow the endangered species Keefer around.

Although Professor Keefer helped set up, at 9:00

a.m. she stopped all discursive language and switched to grunts, moans, laughter,

animal wails and full body language, curling up on a bear rug with Hope DeVenuto

to prepare mindbody for the hours ahead.

For the first hour students giggled nervously as they obediently but very quickly raced through oral presentations of their research in the socio-economic, communications and health science sub-groups. The computers responded by reflecting their work in dazzling pixels and patterns on the Keefer web site. However, this efficiency condensed the Performance into an hour, even though none of the Chairs or official spectators had arrived. Keefer realized that they had exhausted the referent activities without even attempting the performative ones. Her animal body language became more manic.

But some presentations had the seeds of conflict

or drama. For example, student Laurie Cody came as a Gulf War veteran, carrying

a doll, who represented her dead child killed by biological agents. The Puerto

Rican shaman was so distressed by her "performance" that he wept

with her and gave her a present.  A

computer technician was so saddened by what he thought was a true story that

he left. Laurie must have been gifted with naturalistic, Stanislavsky-style

acting technique because she made the whole performance was made up.

A

computer technician was so saddened by what he thought was a true story that

he left. Laurie must have been gifted with naturalistic, Stanislavsky-style

acting technique because she made the whole performance was made up.

Student Abdoulie Bandeh's grandfather was a shaman and since the box-like room reminded him of the tribal fire where stories were told in his native African jungle, he suddenly became more powerful and articulate than ever before as he mesmerized the audience with African tales of shamanism and how corrupt political leaders abuse these traditions. As a reward, he was given an amulet by the Puerto Rican shaman, Carlos Chavez who evaluated every performance in terms of his agenda. Student Brigitte Aponte had met the Puerto Rican shaman in the rainforest (insert image)Professor Keefer was looking anxiously for seeds of a potential fight. She found it after the computer guru Michael Harkins made his presentation about shamanism.

Because I received my PhD in the seventies under Michael Kirby,

I initially tried to document the May 2 1998 Cyberperformance I at NYU "objectively,"

with as few adjectives as possible, and certainly no "value judgements," restraining

myself to succinct visual descriptions that analysed the progress of the performance.

I failed. I failed because I was one of the performers, caught in the electronic

trance/ecstasy of the act, and as a director/coach, my role was kinesthetic

rather than visual/spatial. I'm not sealed off from the cyberperformance:

there is no rind between its fruit and my feelings-- we are squished together,

spitting seeds all over the place. Even my definition of the genre of cyberperformance

is subjective because I thought I made it up, until I read Jon McKenzie's

"Laurie Anderson for Dummies" (TDR 41,1997:30) and realized Anderson too had

created a dramatic intersection of what I call meatspace (our everyday, empirical

reality), deepspace (our unconscious, individual and collective), and cyberspace

(the global magazine of the World Wide Web with its accompanying virtual realities,

envisioned by William Gibson et al. as a "consensual hallucination"). However

Laurie Anderson and I are as different as Merce Cunningham was from Martha

Graham. While Anderson's work is structured around a disjunctive, often interactive

series of games, Cyberperformance I: Humans and Nature grew organically from

a "breach" in the community into a crisis/climax/denouement in meatspace,

followed by completion of "redressive action" and "reintegration" (Turner

1982) of the dangerous foreign element (computers) into the academic community.

Cyberperformance I, like birth, death and marriage rituals, catharsized repressed

emotions and re-established social homeostasis in the academic community.

This life-affirming, didactic social drama is the exact opposite of the nihilist

tradition of absurdist theatre, the subject of a Master's thesis I wrote at

the Sorbonne (Keefer 1969). The seemingly chaotic, multi-focal ambiance of

the event was almost an electronic version of Richard Schechner's Environmental

Theatre (1973) where audience and spectators mingled from the floor to the

chairs to the tables and computers and screens to the ceiling in a wide variety

of conscious and unconscious performance styles. Cyperformance I: Humans and

Nature was free to the community, and all performers and designers performed

gratis, as part of course requirements. There were no sponsors, corporate

or otherwise, other than NYU's role in collecting tuition for the courses

and paying me my modest salary. Anderson's work is the opposite: Laurie Anderson's

performance art, through its use of electronic media and corporate sponsors,

creates an electric body that cuts across the stratum, recombining elements

from the language games of cultural, technological, and bureaucratic performance.

(McKenzie 1997:39) Cyberperformance I simmered with "deepspace" conflicts

among the cultural, technological, and bureaucratic paradigms of performance,

heating the debate between humans and nature, and finally erupting into a

"real" verbal fight between computer guru Michael Harkins and Puerto Rican

tropical rainforest shaman Carlos Chavez. No one thought they were playing

games except the children who drew pictures on the Smart Board, a hyperactive

whiteboard that combines drawing with net surfing. The dramatic structure

of the meatspace event was Aristotelian in its rise and fall, mimicking the

surge and denouement of the male orgasm, because it grew out of the spontaneous

conflict between two men who symbolized the breach in the community. Anderson's

work is much more influenced by Wittgenstein than Aristotle: Decades after

Wittgenstein's death, Anderson will channel his gamey spirit through performance

art, video, film, television and interactive CD-ROM-- mediums in tune with

his Philosophical Investigations, a text she studied in the late 1960s, while

attending Barnard College. (McKenzie 1997:37) In spite of the differences

in style, they are all cyberperformances. I am defining cyberdrama as dramatic

events that occur exclusively in cyberspace, such as MOOS (Multi-Object Oriented),

(see Burk 1998), MUDS (Multi-User Dungeons), some chat rooms and interactive

sites. Hyperdrama (Deemer 1997), like hyperfiction, has a branching, encyclopaedic,

interactive, non-linear structure and can occur exclusively in meatspace.

Since cyberperformances are a triad of the the three spaces, they have a before

and after life that resonates on the internet. There are certain characteristics

of cyberspace that insinuate themselves into the cyberperformance making it

didactive and informative. It is closer to Brechtian theater in that it carries

a message, but it also carries concrete, detailed, coherent information. If

it is just entertaining, it bypasses the main feature of the world wide web

which is to impart information. Brecht's Verfremdungseffekt or alienation

is what I also strove for during the performance: the interplay of immersion

(Murray 1997) and alienation to return from empathy to didacticism. A cyberperformance

is part ritual as well, a way of reaffirming beliefs and celebrating specific

passages of time. Because the web site of Cyberformance I: Humans and Nature

reminded me of an iceberg, I will compare cyberspace to the sea, and the cyberperfomance

to the tip of the iceberg that melts in the organic sun or is hit by passing

ships. However my next cyberperformance will be very different. There are

many things in the sea besides icebergs: big fish, small fish, coral reefs,

vegetation, and of course, sewage and garbage. In Cyberperformance II:Heaven

or Hell? (December 1998), I will try to show the bouillabaise of good and

evil in cyberspace, meatspace and deepspace by combining traditional dramatic

structure with encyclopaedic narratives, games, hyperdrama, hyperfiction and

timespace structures that go backwards, forwards, sideways or into a black

hole. Laurie Anderson's cyberperformance may be more like a hi-tech submarine

that whistles through the sea, up to the surface and back again, flying through

the domains of business, bureaucracy and performativity with superior skill.

. If Freud could return to analyse the Digital Age, he might say that cyberspace

is a wild melange of corporate superego and lawless id, that web sites usually

show some integration of ego, or reality and fantasy, and that a good cyberperformance

would appeal to id, ego and superego. Marshall McLuhan (1964), the media analyst

who described TV as cool, and radio and films as hot in terms of interactivity,

might see cyberspace as frozen, web sites as thawing, and Cyberperformance

I as boiling. When it's not advertising, serving as an international billboard,

it does its best work as digital cave paintings of the collective unconscious

(Harkins 1998), giving the id an audience because both designers and surfers

can unleash their ids in the wild anonymity of cyberspace. Darwin might envision

cyberspace as an electronic jungle, web sites as the survival of the electronically

fittest, and the cyberperformance as the visceral struggle. Jean Alter might

develop a coding of cybersemiotics to describe the triad of "...a show on

the stage and a story in imaginary space, creating a tension between its referential

and performant functions." (1990: xi) When I did an Alta Vista internet search

on cyberperformance, I was given my quotes on the subject from a MOO I attended

at the international Hawaiian TCC98 conference. I was describing my upcoming

cyberperformance which was to be a dramatic synthesis of meatspace, cyberspace

and deepspace. RULES 1) A cyberperformance is a dramatic intersection of cyberspace

(the world wide web), meatspace (our everyday empirical reality), and deepspace

(our individual and collective unconscious.) 2) Each cyberperformance is unique

because of its unpredictable, improvisational nature. 3) Meatspace is multi-sensory,

using smell and touch as well as sight, sound and hearing. 4) Cyberspace must

be live, which means that we see web sites on the internet. 5) Lines are blurred

between audience, performers, surfers and screen. 6) Cyberperformance is didactic,

unlike some drama that is pure entertainment. Because it is connected to the

information highway, it has information to impart; information can be constructive

or destructive. 7) There must be some kind of dramatic conflict, tapping into

the secrets of "deepspace," or it's a multimedia presentation. 8) There is

no dead space-- timespace are used in strange ways. 9) It should affect some

change in the community afterwards. 10) The electronic presence transforms

and continues the cyberperformance energy indefinitely as the imploded meatspace/deepspace

performance explodes into cyberspace. PERFORMING ACROSS THE SPACES Before

I describe my preparations for and kinesthetic impressions of Cyberperformance

I: Humans and Nature, it is best to analyse how that "iceberg" came into being

and before that, how the Keefer web site was built. In spite of my reputation

as a prolific web designer, I consider myself a computer illiterate who still

has trouble with e-mail, an old-fashioned professor who got her Ph.D. in the

days of manual typewriters and card catalogues, and a traditional performer

in many genres. In meatspace I performed in Shakespearean and Restoration

Comedy as Lady Teazle, Lady Macbeth, Desdemona, and Tony Lumpkin (when I was

fat), starred in independent films as a hooker, a demented French teacher,

and an undiscovered star from Macon, Georgia, and created and staged five

one-woman shows. In Experimental Theatre in the seventies, I was one of Michael

Kirby's "Eight People" in his Structuralist Workshop, raking leaves, opening

umbrellas and speaking in foreign languages. I participated in Schechner's,

Meredith Monk's and Robert Wilson's workshops, respectfully taking some of

my clothes off, making strange sounds, and chasing autistic performer Christopher

Knowles around in circles until I was exhausted. In the eighties I switched

to the therapeutic professions (kinesiology/massage) and exorcised my id by

trying unsuccessfully to be a ballerina, a musical comedy star and a screenwriter.

In the nineties I went back to one woman shows and produced "Through the Broken

Glass" and "A Penal Fantasy" in New York, did stand-up gigs at the comedy

clubs as "Sunset Glo," optioned a screenplay about Donald Trump landing on

Mars in an orbiting casino, and published some fiction with Doubleday so I

could teach at NYU. I have survived for 20 years as an adjunct professor by

wrestling-- both metaphorically, and by actually performing wrestling videos

as "Jan Klein."

Harkins turned himself into the protagonist because the room was really his show-- in spite of the symbolic artifacts, it was a room designed and used exclusively for technology. Harkins' research was on the mysterious, sometimes omnipotent power of computer shamans whose drugs are nicotine and coffee, stimulants that focus them in the chaotic environment of technology: "Through his acquired knowledge, the computer shaman can divine trends in the technological future, apply this knowledge to weather the chaos of change, buffeting the enterprise, and most importantly, make possible technology transformations to improve the enterprise or cure what ails it." (Harkins 1998)

Harkins went on to describe the magical properties of the computer: "This animated machine requires proper handling to maintain its benevolent demeanor, and must also be protected should improper discourse unleash its demonic potential. Misuse of neglect of these spirits can start wars, disrupt traffic, cause loss of livelihood and render business inoperative. The soul that inhabits a computer is a fickle and mysterious power, which requires ritualistic observance of its needs, reconciliation when the needs are not met, and prompt intervention in case of security breaches." (Harkins 1998)

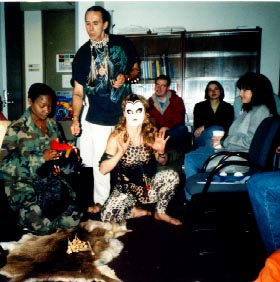

Carlos Chavez, the Puerto Rican shaman, didn't

want any competition, especially from a technology expert and so a spontaneous

fight erupted. Professor Keefer began kick boxing near the computer guru to

awaken his dormant kundalini energy as Chavez boomed from another corner (foreground)

and beat his drum.  A number

of students/performers, Juliet Paez, Daisy Gonzalez, and Mary Kursar, began

to attack Chavez with their theories of shamanism. Keefer let the conflict

develop, trying to ritualize it with martial arts movements and Brechtian

alienation. Then Victor Hinojosa served cat's claw tea while Hope DeVenuto

did auric therapy and Chavez burnt herbs as a way of taking the denouement

from this spontaneous crisis/climax into a social aftermath that resolved

the crisis in the community.

A number

of students/performers, Juliet Paez, Daisy Gonzalez, and Mary Kursar, began

to attack Chavez with their theories of shamanism. Keefer let the conflict

develop, trying to ritualize it with martial arts movements and Brechtian

alienation. Then Victor Hinojosa served cat's claw tea while Hope DeVenuto

did auric therapy and Chavez burnt herbs as a way of taking the denouement

from this spontaneous crisis/climax into a social aftermath that resolved

the crisis in the community.

RULES

1) Each cyberperformance is unique because of

its unpredictable, improvisational nature.

2) Meatspace is multi-sensory, using smell and touch

as well as sight, sound and hearing. 3) Cyberspace must be live which means

that we see web sites on the internet.

4) Lines are blurred between audience, performers, surfers and screen.

5) Cyberperformance is didactic, unlike some drama that

is pure entertainment. Because it is connected to the information highway,

it has information to impart; information can be constructive or destructive.

6)There must be some kind of dramatic conflict or it's a multimedia presentation

.

7)There is no dead space-- timespace are used in strange

ways.

8)It should affect some change in the community afterwards.

Cyberperformance is not the same as Cyberdrama. Cyberdrama is a term that includes MOOS (Burk 1998), MUDS, hyperdrama (Deemer 1995), Virtual Reality(McKenzie 1994), and some kinds of chat rooms. I am defining Cyberperformance as a dramatic intersection of meatspace (our everyday, empirical reality), deepspace (our unconscious, individual and collective) and cyberspace (the global magazine of the World Wide Web with its accompanying virtual realities). When I did an Alta Vista search on cyberperformance, I was given my quotes on the subject from a MOO I attended at the international Hawaiian TCC98 conference. I was describing my upcoming cyberperformance which was to be a dramatic synthesis of meatspace, cyberspace and deepspace. Cyberperformance can celebrate rituals but it also exists as its own performance with a script (the web site), a special time and space and set of rules, even if they are broken, and audience and performers, even if the two become one.

"What if?" a variety of thinkers were to categorize Cyberperformance?

| CYBERPERFORMANCE | CYBERSPACE (Others) | WEB SITES (Self) |

| Keefer's Humans and Nature Cyberperformance I:The tip of the iceberg,melted by the burning sun, smashed by passing ships,Specific time and space in Meatspace with unconscious eruptions from Deepspace, a didactic, cathartic performance ritual where spectators and performers merge in conflict and heat | The fathomless sea, rich, unplummeted and chaotic, Infinite timespace but clean, colorful and cool | The iceberg itself, carved and distinctive, but ever-changing in response to the ocean, A virtual address that can be reached by anyone asynchronously, a new or deeper identity |

| Schechner: Theater, Performance (back to Drama and sometimes Script); electronically-enhanced "Environmental Theatre" that resolves into communal ritual | Drama through Scripts to Virtual Performance; | Script and Drama; |

| Aristotle:Crisis, Climax, Denouement or some biological catharsis (as an anti-feminist, he would not approve of multiple climaxes) | Hypertextuality of Homer with flattened dramatic elements | A bad script |

| McLuhan: Boiling | Frozen | Freezing to Thawing |

| Freud:Id, Ego and Superego |

Superego and/or Id | Ego |

| Turner: Breach, Crisis, Redressive action, some Reintegration | Reintegration or Schism | Breach and Reintegration |

| Brecht: "Learning Play" | Political power struggles | Didactic: Imparts Information |

| Stanislavsky:Breaking the Fourth Wall | The New Realism? | The Fourth Wall |

| Kirby: Computers as Structuralist Objects | Pixels and Patterns in Black and White | Graphics and Text as Distinctive Style |

| Artaud:The Theatre (Purging and Fire) | AND | its Double |

| Nietzche:Imperfect Humanity | Potential Supermen | The Struggle |

| Sartre:Existentialism is a humanism therefore we are all responsible for our "extensions" | You are therefore you surf | I think therefore I upload, but I can choose NOT to go online |

| Darwin: The visceral, meatspace struggle | Chaos | Survival of the electronically fittest |

| McKenzie:(Enhancements) Multimedia extensions from VR to meatspace recursively in an electronic autoperformance (Anderson) or interactive VR (Exhibition, manipulation, deconstruction and reconstruction of self) | Endless fountain of resources with "electronic disturbances" | More of a distinctive performance or presence:"Perform, or else you're a No Body" |

| Jean Alter: Too chaotic to be a performance. Performant and referent functions should be more clearly dileneated. | A feast of referent functions | Cybersemiotics |

The life-affirming, didactic social drama of

Cyberperformance I is the exact opposite of the nihilist tradition of absurdist

theatre. Its organic structure is different from language games although Wittengenstein

is closer to the hypertextality of the internet than Aristotle.

In his documentation of the cyberperformances of Laurie

Anderson, Jon McKenzie describes it as a complex extension of the autoperformance

where cultural, technological and bureaucratic performativity merge in a structure

of games and challenges, more like Wittgenstein than traditional dramaturgy.

(McKenzie 1997) Cyberperformance I was less about speed, efficiency, competition,

transgression and more about celebrating a communal ritual in an electronic

environmental theatre. It was "everyone's show."

There are certain characteristics of cyberspace that insinuate themselves into the cyberperformance making it didactive and informative. It is closer to Brechtian theater in that it expounds a message, but it also carries concrete, detailed, coherent information. If it is just entertaining, it bypasses the main feature of the world wide web which is to impart information. Brechtian alienation occurred throughout the performance: the interplay of immersion (Murray 1997) and alienation to return from empathy to didacticism. A cyberperformance is part ritual as well, a way of reaffirming beliefs and celebrating specific passages of time.

PERFORMING ACROSS THE "SPACES"

In meatspace I performed in Shakespearean and Restoration Comedy as Lady Teazle, Lady Macbeth, Desdemona, and Tony Lumpkin (when I was fat), starred in independent films as a hooker, a demented French teacher, and an undiscovered star from the south in New York, and created and staged 5 one-woman shows. In Experimental Theatre in the seventies, I was one of Michael Kirby's "Eight People" in his Structuralist Workshop, raking leaves, opening umbrellas and speaking in foreign languages; and participated in Schechner's, Meredith Monk's and Robert Wilson's workshops, respectfully taking some of my clothes off, making strange sounds, and chasing autistic performer Christopher Knowles around in circles until I was exhausted. In the eighties I switched to the therapeutic professions (kinesiology/massage) and exorcised my id by trying unsuccessfully to be a ballerina, a musical comedy star and a screenwriter. In the nineties I went back to one woman shows and produced "Through the Broken Glass" and "A Penal Fantasy" in New York, did stand-up gigs at the comedy clubs as "Sunset Glo," optioned a screenplay about Donald Trump landing on Mars in an orbiting casino and published some fiction with Doubleday so I could teach at NYU (where I had received a PhD in the seventies under Schechner and Kirby). I have survived for 20 years as an adjunct professor by wrestling-- performing wrestling videos as "Jan Klein." In deepspace I perform, like we all do, in my dreams. But since 1996 when I began working on my web site , all my conscious performing energies are directed into cyberspace. How does it differ?

What I like about cyberspace, after 15 years of wrestling, massaging and training human flesh, is its colorful cleanliness. Even though information can be scattered and disorganized, one is never overwhelmed with the deep tragedy, imperfection and rage of human flesh. Stories in cyberspace lack the heavy depression of a Russian novel, the angst of European existentialism, the neurotic labyrinths of a Sylvia Plath or the graphic ugliness of much of American naturalism. There is a buoyant optimism online even in the most nefarious and obscene sites, probably because one can always exit with a click of the finger and because no matter how real the virtual reality, one does not have to describe the smelly liquids, decaying flesh and troublesome organs of human bodies. Some people need a specific audience to write or perform, but others are freed by the anonymous audience where they can change their name(s) whenever they want. The "id" domains of cyberspace are still clean and colorful and informative even if the information is destructive or the images provocatively sexual. Smut can only go so far in cyberspace. Humans must download themselves to meatspace if they want to really murder or rape someone, or even kill themselves to latch onto a passing comet and take the journey from cyberspace to meatspace to outer space. Cyberspace cleans up the stale, squished "proximitis" of imperfect humanity. One also misses the physiological high of good sex, cathartic exercise, dance, sports etc. Fights can occur online through "flaming" but they too lack the three-dimensional, wrestling quality of a real fight in meatspace. While this mind body duality can be refreshing in a place like New York where one is suffocated by humanity in subways, buses, apartment buildings, coffee bars, it is nevertheless a duality.

When I participated in MOOS for the TCC98 Annual Conference as a writer and presenter, I had another experience-- a wild, uncensored freedom of imagination, a new sense of intellectual nudity and transparency as I typed 12 hours a day into the Coconut Cafe and the Conference Rooms.

There is a difference between my anonymous adventures in cyberspace where the id can be unleashed and my presence at the NYU server where reality and fantasy must merge to serve a hopefully constructive educational process. Although critics have said my web site has a strong presence (Hargitai and Keating 1998), I think of it as a collaborative mosaic, a Brechtian "learning play," where all theatricality subserves the educational objective. It's a work in process, always changing, never hierarchical because my students are much better photographers and poets than I am. Everything we build lasts: unlike meatspace performances, nothing is ephemeral unless we erase it.

But as my students designed their Humans and Nature web site for my writing class at NYU, I sensed it had become an enormous iceberg, in need of melting in the sun during some kind of a cyberperformance. Not all web sites are like icebergs. My Home Page is a coral reef, a colorful thing to be surfed without coming up for air. Laurie Anderson's cyberperformance may be more like a hi-tech submarine that whistles through the sea, up to the surface and back again, flying through the domains of business, bureaucracy and performativity with superior skill.(McKenzie 1997) The sea of cyberspace is filled with small fish and whales, coral reefs and exquisite deep sea life, but like the sea we have polluted, it has a lot of garbage and sewage. Therefore some cyberperformances could be garbage.

After spending two years designing over 300 web pages of graphics, research, poems, stories etc. I wanted to find a way to pull this work together in some dramatic, combustive way. I wrote a paper about how the internet changes the conventional classroom (Keefer TCC98:"Combining Meatspace, Cyberspace and Deepspace") and I realized that for the classroom to work in the twenty first century, it must give the students something they could not get online, could not get from traditional lectures, collective chat, multimedia. I had given several multimedia presentations for faculty and realized it was just an explanation and elucidation of what was already on the screen. I was also disturbed by what was happening to the students' work in the computer-enhanced writing research classes. The webfolios of graphics, poetry, interviews, essays etc. provided the right brain counterpart to traditional left brain research in the MLA and APA styles and this combination gave the work more depth than before. However, argumentation was missing. In the fluid world of hypertext, they had trouble developing their thesis and even more trouble defending it. They lacked a sense of conflict. At first I thought they just needed more lectures on logic but after expounding on Aristotelian, Boolean and fuzzy logic for hours, I realized they were missing something more basic-- a sense of audience.

One day in the computer lab, I looked at all their bodies slumped forward over the keyboard, their fingers and wrists cramped from hours of typing, clicking and scrolling, their feet curled up on the floor, their neck and back muscles tight and bunched up. Their eyes had the glazed look of drug addicts and their auras were grey and transparent as if they were about to dissolve into the screens themselves. As a fitness specialist as well as a multidisciplinary writing professor, this is a side effect of cyberspace I abhor. No matter how wild and wonderful are adventures are in cyberspace, we cannot let our biological bodies disintegrate. A cyberperformance is a way for cyber script writers to experience kinesthetic immediacy.

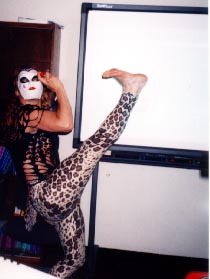

The night before the cyberperformance, as we were setting up, I feared that it would turn into another "multimedia presentation," especially because the students were getting stage fright when they heard Chairs of Departments and Deans would be there. I told them to wear costumes but they felt too self-conscious. That night I wandered around my apartment, sleepless, looking for a way to bring this performance to life. I gathered a costume together of leopard skin rags from a dance I did ten years ago, a wig from the same period when I was trying to be a musical comedy star, and a mask that had developed a life of its own covered with cat hair, and a small rip near the eye that dripped a tear. I put on the costume and knew it was a success because it scared my cats to death. Ever since I was admonished for wearing spandex to teach, I have had a reputation at NYU for being weird and wild. I decided to go all the way and dress up in leopard skin rags as an endangered species, thereby synthesizing the Humans and Nature theme with the anxiety over the survival of the professor in the information age. But I no longer felt "transparent," in that electronic trance. I was now vulnerable again and had to "double" myself, to put on masks and wigs to become a character.

Then I pulled out an old copy of Richard Schechner's Environmental Theater and began reading about shamanistic performance. I was particularly struck by the following: "Shamanistic performance is a protagonist-antagonist conflict by means of which the secret wishes of the community are exposed and redistributed." (1973:189)

In the flyer I had advertised that there would be a shamanistic performance, because many of the students were doing research projects on shamans. Juliet Paez had gone to Arizona over spring break and found one in the parking lot; Abdoulie's grandfather was a shaman and he wrote about how the current African leaders were manipulating shamanism to rule the people as despots. Michael Harkins was doing a cross-disciplinary study with computer shamans because he owns a computer consulting company and Brigitte Aponte found a shaman in the rainforest while vacationing in Puerto Rico. Health science majors did studies on healers as shamans. By focusing on shamanism, I could illustrate cross-disciplinary research more effectively and simply, showing how the disciplines of computer science, political science, health science, literature, psychology, philosophy and anthropology all provide different perspectives or crosses on the understanding of shamanism.

As we set up the space on Saturday morning, it reminded me of a condensed, cave-like, electronic version of The Performing Garage in the seventies. I hoped the audience and performers would mingle as they had in Schechner's performances but since my students weren't performers, I knew it was going to be very difficult. I wanted an implosion in meatspace to explode into cyberspace. If the room had been an auditorium, it would have been too easy to get out, to avoid conflict. I was expecting the conflict would come from a student getting mad at me because she couldn't fulfill the assignments; instead a more cosmic conflict developed between the Puerto Rican shaman and the computer guru over who was the real shaman. Although I don't like to delude myself with feelings of specialness or omnipotence, I was acting the role of a kind of shaman, a "trickster," as the Puerto Rican shaman Carlos Chavez described me, a kind of social stimulant and irritant who was really trying to turn a multi-media presentation into a cyberperformance. Through my body and memory I combined modern dance, mask transformation, kick boxing, wrestling, comedy, improvisation and therapy with my role as professor.

The only prop that worked for me was the bear rug. My goal was to unite information with emotion and memory, to ground expression in a meatspace reality with oral polemics and conflict and to provide a venue for display, exhibitionism and communal interaction. Yet Chavez, the Puerto Rican shaman, was the real antagonist who placed himself in every scene, terrifying, fascinating and annoying spectators as much as any goblin, wolf or bad guy. In order to enhance the conflict's energy but alienate it from personal attack, I went over to the computer guru and began to playfully kickbox him. Later Chavez, the Puerto Rican shaman, said he couldn't look at me because I was too strong. I wanted the students to be strong enough to fight him. I pressed Dianna's feet into the ground and rocked on them with my whole body to ground her as she delivered her poetry. I touched Juliette's shoulder comfortingly. I picked up their children and carried them around. I stood on a table and pressed my head against the ceiling when the fight got out of control.

For four hours I was in a hyper-aroused, "ectstatic" (Artaud 1958), multi-focal state, the opposite of the clear, calm, playful focus I experience online. As a performer I was never self-conscious, but only judged my performance in terms of the flow of the entire event, like a kinesthetic, not a visual-spatial, director. Ironically I left the performance a few minutes early to teach two hours of aerobics. I was happy the performance could exist without me.

THE AUDIENCE

I felt I was listening to the natural rhythms of everyone and encouraging the unfolding of the most inevitable conflict. The audience was principally members of the NYU community although two people came because it was posted on the internet.A passing surfer who happened to see the cyberperformance advertised online, Sheldon Siporin, said he was surprised it was so "linear;" he was expecting a hyperdrama (Deemer 1995) with branching narratives and interactive choices. (Murray 1997). In spite of the internet's hypertextual nature, when a communal performance was allowed to develop organically, it grew into the traditional Aristotelian model of exposition, crisis, climax, denouement. Could this be because the protagonist-antagonist conflict was between middle-aged men and that the biological rhythm of drama imitates the rise and fall of the male orgasm? Although some of the female performers were constantly erupting and interrupting the event with minor crises, the major conflict occurred between the computer guru and the Puerto Rican rainforest shaman. Abdoulie Bandeh's tales of the political abuse of African shamanism, eight year old Matthew Harkins recitation of the Jabberwocky, Laurie Cody's convincing naturalistic presentation of a Gulf War veteran with a baby killed by biological agents, and the factual discourses on man's rape of the environment only enhanced the conflict between technology and nature: which God or Shaman do we want to serve? The seeds of this drama came from the dialectic of the course Humans and Nature .

This conflict also symbolized a deep-rooted breach in the academic community, between those who love and those who hate computers, those whose careers and academic performances are enhanced by technology, and those who feel threatened. For the past year, almost every faculty meeting had witnessed some form of argument, dispute or breach regarding the use of computers in the classroom. Students complained incessantly to faculty and administration about their insecurity and illiteracy regarding the new medium. So it was fitting that this performance would be a crisis where "redressive action" (Turner) would be taken to reintegrate or allow the breach to cause a real schism. The professors who hated computers unconsciously sat with their backs to the screen. Three students from the afternoon class stood at the door and were so terrified by Puerto Rican shaman Chavez that they ran away. Everyone in the "electronic environmental theatre" had a vested interest, conscious or unconscious, in the outcome of the fight between the computer guru and the Puerto Rican rainforest shaman.

At the end of the cyberperformance, there was a feeling of communal ecstasy, because the experience had included everyone and their varying emotions. Afterwards the euphoria spilled into afternoon classes and workshops and faculty parties at night. Somehow computers were no longer malevolent gods-- they had been reintegrated into the community. What started out as a drama became a script through the web site, theatre through computers and performers, and finally social drama and narrativity (Turner) through the cyberperformance. This is how I explain the extreme reactions of the audience from running away, giggling, fear, fighting, playing etc. There was an expression on everyone's face. The computer age needs its rituals now even more than the jungle does. For me the goal of the organic professor on the inorganic net is to bring theatre back into the classroom. The cyberperfomance then becomes the dramatic intersection of cyberspace, meatspace and the deepspace of our unconscious, collective and individual.

In the future, I plan to stage cyberperformances around the themes of the Keefer Brain Gym, Writing: Time and Space, Lovers and other Monsters, Heaven or Hell and other sites that need "thawing."

References

Alter, Jean. 1990. A Sociosemiotic Theory of Theatre. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Aristotle. 1988. Poetics, trans. Gerald F. Else. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Artaud, Antonin. 1958. The Theatre and Its Double, trans. Mary Caroline Richards. New York: Grove Press.

Brecht, Bertolt. 1964. Brecht on Theatre, trans. John Willett. New York: Hill and Wang.

Burk, Juli. 1998. "Moov-ing Online: A New Venue

for Teaching and Making Theatre."

Darwin, Charles. 1993. The Portable Darwin, eds. Duncan M. Porter and Peter W. Graham. London and New York: Penguin Books.

Deemer, Charles. 1 September 1996. "Hyperdrama

and Virtual Development: Notes on Creating New Hyperdrama in Cyberspace."

Freud, Sigmund. 1994 (1930). Civilisation and Its Discontents, trans. Joan Riviere. New York: Dover Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

Grotowski, Jerzy. 1968. Towards a Poor Theatre. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hargitai, Joseph and Keating, Ann. 1998. The Wired Professor. New York: New York University Press.

Harkins, Michael. 1998. "Computer Consultant

as Shaman."

Joyce, Michael. 1995. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Keefer, Julia. 1969. "La Chute de la Tradition

Theatrale." Unpublished Master's Thesis. La Sorbonne, Paris.

1990-1991 "Through the Broken Glass" one woman show

performed in New York.

1995 "A Penal Fantasy" one woman show performed in New

York.

1996-1998 Keefer Web Site. <http://www.nyu.edu/classses/keefer>

1998 "Combining Meatspace, Cyberspace and Deepspace."

LaFarge, Antoinette. 1995. "A World Exhilirating

and Wrong:Theatrical Improvisations on the Internet."

Laurel, Brenda. 1993. Computers as Theatre. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing.

McKenzie, Jon. 1997 "Laurie Anderson for Dummies."

TDR 41, no.2:2.

1998. "Genre Trouble: (The) Butler Did It," in The Ends

of Performance, eds. Peggy Phelan and Jill Lane. New York: New York University

Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media:The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Murray, Janet H. 1997.Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1954. The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufman. New York: Penguin Books.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1965. What is Literature? trans. Bernard Frechtman. New York: Harper & Row.

Schechner, Richard. 1973. Environmental Theatre.

New York: Hawthorn Books.

1988. Performance Theory. London and New York: Routledge.

1990. By Means of Performance, eds. Richard Schechner and Willa Appel.

New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stanislavsky, Konstantin. 1961. Stanislavsky on the Art of the Stage, trans. David Magarshack. New York: Hill and Wang.

Turner, Victor. 1982. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: Performing Arts Journal Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1980. Culture and Value. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.