Saving The Soul Of Harlem

By Marsha Taylor

2007

How is it that two people can look at exactly the same thing and have entirely different perspectives? What appears to be a dark, hard, scary place to one; can represent a soft, warm, and welcoming home to another. Looking out of the window of my grandparent’s 25th floor apartment window in The Polo Grounds Projects, the sunset used to mesmerize me. Bright yellow with a dark orange mix of color sitting right on top of a clear, light blue sky, it was amazing to me. It was just there, and I would always happen to catch it. A little girl caught in the moment. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the vision was being permanently painted onto my brain, so that I’d always be able to see that very same sunset (even when I was no longer standing by the window). Still, silent, strong, and beautiful all in one – the colors of the sunset didn’t discriminate. The beauty was as perfect in the projects as it was in the suburbs…and while the world I knew, a concrete jungle, could be as frightening as the darkness in the woods, as menacing as a bear slowly walking towards a camp fire; it could also be as breathtaking as the highest mountains and as calm as the silence of the wilderness. For me though, it was just home…and home was Harlem, New York. Birthplace of The Harlem Renaissance, it remains the epicenter of black culture - a place which throughout the years would be transformed time and time again, and would, little did I know all those years ago, eventually find itself fighting for the soul of its very existence.

“The sun was sinking. The hard stone of the day was cracked and light poured through its splinters. Red and gold shot through the waves, in rapid running arrows, feathered with darkness. Erratically rays of light flashed and wandered, like signals from sunken islands, or darts shot through laurel groves by shameless, laughing boys. But the waves, as they neared the shore, were robbed of light, and fell in one long concussion, like a wall falling, a wall of gray stone, unpierced by any chink of light.” (Woolf, 207)

Many people misinterpret what it’s like living in what is known as “the ghetto.” The “hard stone…cracked...darkness” seems to be synonymous with descriptions of what some believe about those tall, skyscrapers where many families live and little kids play. The thought of these city owned buildings conjure up images of places that are “robbed of light”, elevators that smell of urine, and shameless people who don’t want anything more out of life. Of course, many who believe that have never set foot in a project housing area, much less lived in one. Growing up in The Polo Grounds projects in Harlem, I only knew that living there felt like the greatest place on earth. It didn’t feel like anything was missing. The tall buildings could be compared to brown and rust colored trees stretching toward the sky with seemingly no end. It was an amazing sight, whether you were looking up trying to figure out who was screaming your name from 25 flights above, or looking down and screaming out the name of one of your friends who, being so far away looked more like an ant than a human being. Just as Virginia Woolf described the ocean in her book The Waves, “Erratically rays of light flashed and wandered” in the projects too, except they glistened and signaled off of the many windows in the buildings. It always seemed bright and sunny up there in the sky. Those buildings were so powerful in their stature, quietly commanding. They were never swayed by an angry wind or frustrated sun. They were protectors, providing shelter and safety, the way trees and caves protect their inhabitants. From above, like on a mountain top, it was awe inspiring, trance inducing. When night fell and the bright yellow-orange of the sunset had faded into the now dark sky, the walls of our tall, brown, stone buildings sat silently; and like the waves, were “unpierced by any chink of light.” It was peaceful. It was perfect. It was Harlem.

Harlem…A Place of our Own

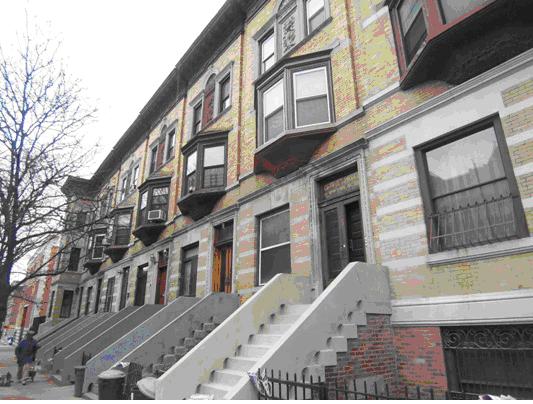

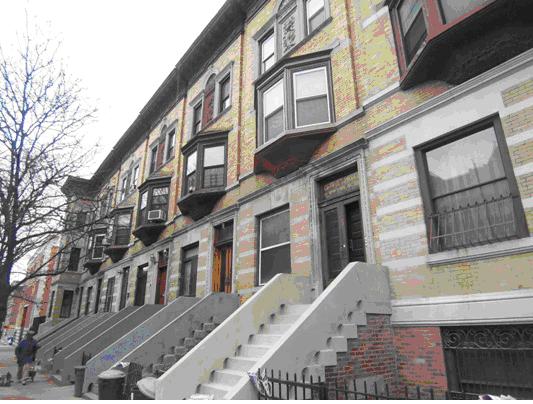

Outside of the many housing projects in the area, Harlem was a community just like any other with beautiful brownstone homes, apartment buildings, schools, stores, and people, searching for a better way of life Originally inhabited by Europeans in the early 1600’s, Harlem, back then, was known for its attractive farming land. Under the leadership of Peter Stuyvesant, the small territory was first named Nieuw Haarlem (New Haarlem) in 1658, after the Dutch city of Haarlem - British immigrants eventually renamed it Harlem (Ellis 52). There were only a handful of blacks in Harlem at the time that had been brought over by the Dutch to work as slave laborers. They played a huge role in building the first street road which connected Harlem and lower Manhattan. That connection began the transformation of Harlem from just an agricultural area into a more desirable residential one. By the 1800’s, Harlem had become a community representing status, elegance, and class. There was, however, a small population of black farmers who resided in a small enclave within Harlem. With the construction of a new railroad system, developers eagerly began building more housing in anticipation of an influx of more well-to-do residents. That all changed as the economy began to experience a downward spiral. With Harlem having become more a mix of industrial and residential land, the agriculture business had become virtually non existent. Construction plans for the railroad system were stalled and delayed, causing a decline in real estate value. It hit Harlem landlords hard and many newly constructed buildings sat empty…waiting for a rush of new residents that never came. When they eventually did arrive, they weren’t White. Despite their reservations, landlords had little choice but to offer apartments to blacks and to new immigrants including Jews, Italians, and the Irish. More blacks began moving into Harlem due to the housing availability, although some landlords charged very high rents - sometimes even dividing up apartments which caused overcrowding. Still, it was a place where black people felt welcomed, where they saw other people who looked liked them, and where they felt they had a chance for a better life. Other blacks migrated north to escape the horrendous conditions of racism in the south. Some came from the Caribbean. Hundreds of black laborers were recruited to work in the north during World War I and they too settled in Harlem. Before long, black churches began springing up in the neighborhoods. At first, white residents and business owners attempted to keep blacks from moving into the area; but, they were unsuccessful and soon left in droves - some even selling their homes at a loss. By the early 1900’s, Harlem was a predominantly black community. It was the first time for many of feeling like they were in an environment that they could call their own. It was a place to call home, a place where they belonged, and there was a sense of pride and dignity that came along with it. Living in Harlem meant an opportunity for progress. Black people, who for so long had been oppressed, took advantage of being able to freely express themselves and their intellectual and creative energy during this era would become a staple in American history. It would expose the world to black culture – their intelligence, their art, their literary works, social commentary and political prowess, and of course, their song and dance. It would forever be known as The Harlem Renaissance.

“But here and now we are together,”…”We have come together, at a particular time, to this particular spot. We are drawn into the communion by some deep, some common emotion. Shall we call it, conveniently, ‘love’?” (Woolf, 126)

Remembering Harlem

It was 1930 when Thelma Johnson-Grant arrived in New York from Baltimore, Maryland. She well remembers a time when blacks had to sit in back of the bus, when Jim Crow was the law of the southern land, and when the Harlem Renaissance was born. “I’ll never forget it,” she says. “We didn’t think too much about color. We went to the clubs to listen to our music, Smalls Paradise – I was in there doing the lindy(hop)…The Lenox Lounge, The Cotton Club, and The Savoy - I was in there with Duke Ellington….and that band was playing! I was young, I loved dancing!” Harlem was a beautiful place, she recalled, as we sat on her couch in the same apartment she’s had for almost 40 years. She described it as a place where “you were safe to walk the streets at night” and rent parties were a regular occurrence for most black people trying to make ends meet – “I had one”, she tells me with a laugh, “…just a good time, no fighting…there was still racism, but not like in the south where they would hang you from a tree.”

Many residents of Harlem can recall the good ole’ days which, for them, may have been a mere 20-30 years ago; but for older Harlemites, like Ms. Johnson-Grant, remembering Harlem during its heyday, is truly something special. She, like so many others, came north with the hopes and dreams for something better. It became known as The Great Migration (Ryan and Myers 14) and by 1923, as many as 150,000 blacks had settled in Harlem (Black Harlem). The Harlem Renaissance began in the 1920’s and lasted through the 1930’s until The Great Depression. Throughout that time, however, Harlem’s new black community established a middle class of homeowners and residents who were expressing themselves in ways that put the black culture in the forefront and forced the world at large to recognize them in a completely different way. From a political standpoint, blacks, for the first time, established organized efforts to fight for their rights. Racism, while not as bad as in the south, was still very prevalent in the north. Historian and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois emerged as one of the early leaders in the struggle against racism. He formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Along with the likes of Marcus Garvey, who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and Booker T. Washington, who fought for education for black people, Harlem became the center for black aexpression. Blacks established their own newspapers and magazines in order to raise awareness about issues relating to them. The leaders advocated for social equality and justice, and inspired black people to unify and challenge the status quo.

Also emerging from the shadows of Harlem during this ear were literary writers and poets who documented the black experience and celebrated their heritage. Their works would become the first written by African Americans to receive national recognition, being published and awarded for exposing the world to black culture. Among them, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and James Weldon Johnson, whose creative novels, plays, and poetry painted vivid descriptions of life during that time and would inspire generation future generations of African American authors. The economic pressures caused by The Great Depression forced many of these writers to leave Harlem. Some simply stopped writing as the focal point for blacks shifted to a more economic and social issues.

Artistic expression in the performing arts was a major part of the Harlem Renaissance where blues and jazz music introduced the world to some of the most memorable artists in American history. From the smoky voice of Bessie Smith to the big band sounds lead by Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, blacks performed at Harlem venues including The Cotton Club, Smalls Paradise, The Apollo Theatre, and The Savoy Ballroom, where the dance, the Lindy Hop became popular. Blacks began performing to an ever increasing white audience who became fascinated with black culture. Although many of their performances were for “white only” audiences, black artists were able to create their own nightlife culture which enabled them to affirm their cultural roots through song and dance.

Between the literary and artistic movement of blacks during the Renaissance, Harlem served as the unifying location. As author James Weldon Johnson observed some 87 years ago, in his writing, “The Future of Harlem”:

“Some may fear that the Negro will be driven out of Harlem…In my opinion he is in Harlem to stay, because his condition in this section is entirely unlike it ever was in any of the other sections…Negroes are beginning to own Harlem… And so I feel confident that the Negro is in Harlem to stay…wide and beautiful streets, no alleys, no dilapidated buildings, a section of handsome private houses and of modern apartment and flat houses, a section right in the heart of the empire city of the world (100).

Throughout the ensuing decades, Harlem continued to be central for blacks; however, unlike during the Renaissance, the community began to fall into disarray as many of the “middle class” blacks began moving out of the neighborhood. Harlem still remained a home for many though. It was still that little corner of the earth that black people felt was theirs and despite the dilapidated and decaying structures, it still didn’t seem that bad…at least for some.

“We can all dream about the good old days. We never thought they would end.” (Eileen Diaz, longtime Harlem resident)

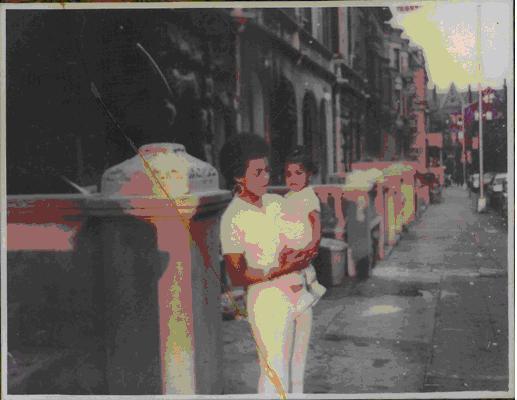

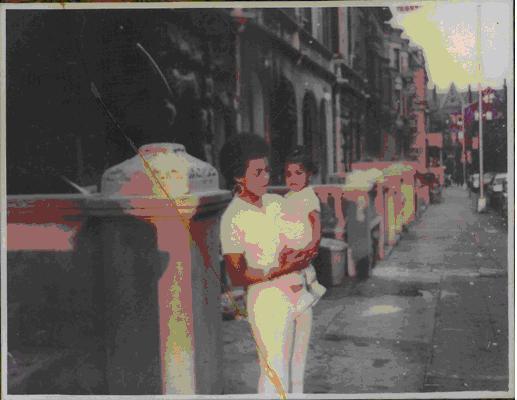

Marsha (age 1) and mom in Harlem, 1970

For me, Harlem was the only world that I knew for a very long time. From watching television and reading books, I knew that there were other ways and other places to live, but where I was seemed just fine. As a matter of fact, I often felt like anybody who didn’t live in my neighborhood was missing out! Perhaps some of the adults saw it differently, especially those who could remember when Harlem was beautiful during the days of the Renaissance, before abandoned buildings replaced immaculate pre-war buildings and beautiful brownstones; before drugs replaced art and literature; and before drug dealers replaced authors and activists. Yet through my young eyes, I had everything I needed – family, a good school with great teachers, and of course, my friends.

Yes, I remember when we were young, walking those mean streets without a care in the world. We were proud of our neighborhoods. Never felt poor. It wasn’t until I became an adult that I realized we were. I guess because we were so rich in other ways. We never felt deprived. Seems like we had everything we needed right there in the neighborhood. Sure, we wanted a better life, but it wasn’t like the one we had was so terrible. At least that’s the way we saw it. I don’t ever recall anyone feeling like the lack of other races in the neighborhood was the cause of it looking so bad. Back then, it seemed like there were only Whites and Blacks, with a sprinkling of Puerto Ricans and we all liked where we lived. I sure didn’t want to trade where I lived for anything in the world! Although I must admit, when I was 9 and invited to spend the night at Keisha Blount’s house, I was in absolute awe as I walked in the front door and saw the beautiful white carpet, the stairs (“Wow! only rich people have stairs in the house!”) and one of those “Brady Bunch” ovens in the wall. “Her family must be rich!” I thought. The fact that she just lived in Freeport, Long Island in a simple, modest home didn’t really occur to me. All I knew was it was very different from where I lived. It was really nice, but I was more than happy to go right on back to apartment 5G on West 146th Street when the visit was over. Who needed stairs anyway?

The Projects

Summertime in Harlem was the best! Taking long walks from 155th down to 125th, bag of potato chips in one hand, Tahitian Treat or Mello Yellow soda in the other, just strolling along – Ah, life was good! Waving to the boys playing basketball in the hot sun – looked like it had to be 25 of them under one hoop! Rutger Park always seemed crowded. Some of the best ballplayers came through those courts, but for us, it was just a place to hang out and play. Asking for a quick turn to jump rope from our girls who were playing double-dutch; yelling at one of our friends zooming by on a bike to ask for a ride (not everybody could afford a bike – that was a Christmas present or something special you got for your birthday). We always smiled at the little kids getting wet in the sprinklers or climbing on the monkey bars, but there was always some trouble maker who wanted to take the water games too far. All I knew was that nobody had better splash water from that open hydrant on my cute, terrycloth shortset and new Prokeds sneakers! I probably wouldn’t get another pair until it was time to go school shopping!

Those walks…the buildings we passed were old, abandoned, and burned down and out, but nobody cared. We sure didn’t. There were enough little corner stores around them where we could go buy candy, pickles in bag, ices, or a hero sandwich, and that was all that mattered. Funny, but it sure seemed like there was always a church stuck in between those old buildings, too, just blending right on in with the rest of the surroundings. Our community was like a big, giant apartment, the buildings were the furniture, and we were the tenants. Everybody knew everybody – their families, their lives… and somehow, we all became intertwined. We knew who worked where, who had a fight, whose cousin was coming to visit, who graduated, who got left back, whose was having a party, who was on punishment, and of course, who was “going out with” who. Whether it was food shopping with your grandmother on Saturday (it was so crowded in the supermarket!) or getting to hang out a little later with your older sisters and brothers (well, in my case aunts and uncles)…life was all good! And when the DJ’s started setting up their turntables and crates of records in the park, we knew it was going to be a jam all night, and we couldn’t wait to hear the first sounds of music start blaring from those huge speakers:

Rutger Park & Basketball Courts

“I said a hip hop, a hippie, a hippie hippie

hip hip hop and ya don’t stop

a rockin to the bang bang boogie say up jumped the boogie

to the rhythm of the boogity beat”

(The Sugar Hill Gang. "Rapper Delight”)

Little did we know, 30 years later, rap music and hip hop culture would become a global phenomenon…all starting right in our parks and neighborhoods. It was all ours. Our music, our park, our old, abandoned buildings, our bodegas, our projects, our churches, our people. It was home and we didn’t need anybody to come and make it better. It was just fine the way it was…or was it?

Crack City, USA

In the 1980’s, Harlem was decimated by the crack cocaine epidemic. Although the 1960’s and 70’s had seen their share of drugs and crime in the community, nothing like this had ever been experienced. As longtime resident Angela Hampton described about Harlem in the 70’s, “There were a lot of abandoned buildings, a lot of drugs…but it still had a feel to it, ya know? You went outside and you enjoyed it, you wasn’t really scared to go outside because this was a part your livelihood…you could still go outside and play as a kid…” By the mid 80’s however, crack had overtaken entire neighborhoods, destroyed families, and made addicts out of people, young and alike. People were afraid. Those old buildings that had been vacant for so long became crack houses. Many of those streets where young kids used to play became too dangerous to even hang outside on a hot summer night for fear of bullets flying. Where it seemed that, in the past, only older men, the “hustlers” of Harlem, would conduct their “business” with some ironic regard for the community, the new generation of drug dealers had a completely different attitude. They were now much younger and they had little, to no regard for human life or for the “street code of ethics”, which limited where, and to whom, dealers would sell their product. Instead, sold crack to anyone – mothers, fathers, young kids, pregnant women, friends, and sometimes sadly, even family. The profits were huge for those who had never imagined making such money. Now able to buy homes, cars, jewelry, and nice clothes, becoming a crack dealer had all of the trappings of “success,” and Harlem, even with all of its self destruction, still managed to remain a global trendsetter. Miss Hampton states, “Out of all of the boroughs, Harlem always seemed to stand out… what we wore, what we drove, when they speak of New York in terms of style, they’re talking about Harlem.” The Harlem community was still reeling, however, from the influence of crack and it seemed no one was stepping in to assist the people during this time of mayhem. According to Assemblyman Keith Wright, in the 1980’s, 80% of the real estate in Harlem was owned by New York City because most landlords had walked away from their buildings due to the deterioration of the community (Like it Is). He called New York City “the worst landlord in the world” and blamed them for not taking care of their responsibility, allowing those buildings to become run-down shells. As he explained to host Gil Noble on the television talk show “Like it Is”. Over 50,000 blacks fled New York during that era. It was a bad time for New York. It was a really bad time for Harlem, but as always, those who believed in the Harlem stuck around and tried to retain some of the essence of the community. For some, they couldn’t afford to leave. For others, despite the drugs and the crime, they didn’t want to leave. Harlem was home and it still felt comfortable. “Woo that was fun!” said Miss Hampton of Harlem in 1987. “ Just the whole feel of the block parties and the um, it was a lot of fun….when you really start thinking back to it, the jams in the park, the whole…still drug infested, but now we was up to the crack epidemic, but nonetheless, it was still a good place... Harlem still had, you had people that worked everyday…those who sat out on the park benches…we were still family oriented….back then, we were the village.”

So Harlem survived the crack epidemic. Those who stayed and had hoped and prayed for better days were getting some relief as drugs and crime were finally being dealt with under new police policies enacted by former Mayor David Dinkins. In 1993, when a new administration took office under Rudolph Guiliani, those policies were enforced ten-fold and Harlem found itself on the upswing again (Wikipedia). Although, changes were slight, there were grumblings of plans for revitalization in a “Renaissance” sort of way. It seemed far fetched to many who had just come through the most difficult era for blacks since slavery. Small efforts were made to encourage residents to purchase real estate in the area, but few could imagine buying an abandoned, burnt out shell of a house, even at the give away price of $1.00. Many of the buildings were still right next door to crack houses, on streets not completely cleaned up of the dealers. Although improvements had been made, few could imagine that Harlem would ever return to the picturesque beauty of the days of the Renaissance. They had no idea what was in store for their long suffering community.

A Change is Gonna Come

By Sam Cooke

I was born by the river in a little tent

Oh and just like the river I've been running ever since

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

It's been too hard living but I'm afraid to die

Cause I don't know what's up there beyond the sky

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

I go to the movie and I go downtown

somebody keep telling me don't hang around

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Then I go to my brother

And I say brother help me please

But he winds up knocking me

Back down on my knees

Ohhhhhhhhh.....

There been times that I thought I couldn't last for long

But now I think I'm able to carry on

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Change is inevitable. It’s one of those things in life that is simply guaranteed to happen in just about every area of life - time, age, seasons, prices, music, people – everything must change eventually. Often times though, people are resistant to change. Fear, uncertainty, and being comfortable with what is familiar, are just a few of the reasons people often reject the notion of change, even when it can be change for the better. In response, people might organize and protest, petition, and in extreme cases, go to court to fight against change. There are many instances, however, when change is welcomed. Perhaps not always with arms wide open, ready to embrace it all at once, but certainly with optimistic caution. Such is the case in Harlem as change envelopes the community.

Residents of Harlem had already bared witness to the incredible transformation of New York’s famed 42nd Street area from a seedy, dangerous haven of drugs, prostitutes, and porn shops into a bright, clean world renowned tourist attraction filled with Disney stores, museums, and new restaurants. But could something like that ever happen in Harlem? Few could ever imagine neighborhoods cleaned up of the graffiti, drugs, and abandoned buildings. Despite blueprints that displayed an entirely new look, complete with a new shopping area, theatres, stores, banks, and most of all, tree-lined blocks full of renovated brownstone houses and new, beautiful buildings; it simply to be nothing more than a few activists and local politicians blowing hot air. Even the thought of change was simply incomprehensible.

“But now the circle breaks. Now the current flows. Now we rush faster than before. Now passions that lay in wait down there in the dark weeds which grow at the bottom rise and pound us with their waves. Pain and jealously, envy and desire, and something deeper than they are, stronger than love and more subterranean. The voice of action speaks” (Woolf 142).

Then, slowly but surely, change eased its way into Harlem. Little by little…sometimes so subtle, residents didn’t even take realize they were already a part of what was becoming a journey towards new beginnings; a journey that would open and close doors all at the same time. Some were prepared…many were not. Under Mayor Guiliani, Harlem’s real estate, owned by the City of New York, was sold to developers who saw the area as prime real estate. And thus, the sound of change was not longer silent – construction on every block, the chatter of businessmen discussing what would be built on the next vacant lot; the look of change was apparent as signs that read “1,2,3 BEDROOM CONDOMINIUMS FOR SALE” popped up on the side of beautiful new buildings; the feel of change could no longer be denied as the person standing in the grocery checkout line in front of and behind long time residents was of a different race; it wasn’t until change was right there in their faces, that it could no longer be denied.

Some decided to join in the journey towards change - after all, it was happening despite how they felt about it. Yet, others resisted whole heartedly. The journey, they felt, excluded them, moved on without sending them a personal invitation. It was new, and different, and scary, and intimidating. What were they going to do about all of these changes? What could they do? In short, the answer was, very little. Those who did not make a decision had one made for them. Change was happening and it was up to residents to find ways in which to be part of “the new Harlem”… or be left behind.

THEN

NOW

Interview

- How long have you lived in Harlem?

- “I’ve lived here all my life. I was born at right at Harlem Hospital. Harlem is where I

was born and Harlem is where I’ll probably die, and that’s just fine with me. My old ass

ain’t goin’ nowhere! (laughing)”

- What has been the biggest change you’ve seen in Harlem over the past 30 years?

- “Everything…all the new buildings, all these new stores, all these White people walking down the street like “OK we live here now” (laughing), it crazy! I mean, don’t get me wrong, it’s definitely a change for the better, it’s just that it’s like a different place now. If somebody who used to live in Harlem a long time ago left and just now came back, they would be buggin’ out like ‘Where am I? This is not Harlem!’ You know when we were little you ain’t see a White person nowhere uptown. Now, they’re all up in the mix, walking their dogs down the street, walking with their families on 125th Street. Oh my God, it looks so crazy! Even the Chinese people started living here, too. They all be out at night going to the new little lounges, the movies, and the restaurants, and they are not scared at all. They are very comfortable in Harlem. It still bugs me out sometimes when I see them.”

- So how do you feel about that – the new residents of Harlem? White people…Asian’s

A. “I mean, it doesn’t bother me at all. People can live where they wanna live as long as

they don’t mess with me, I don’t have a problem with it. What I do have a problem with

is the fact that my ass can’t afford to buy one of them nice brownstones or live in one of those new condos they built.

- So where are you living now?

- “I’m still in my grandfather’s old apartment on the 13th floor. It was big enough for

me…and the kids. I’m not gonna find a 3 bedroom apartment up here for less than like $2000, if that. I can’t afford that! So me and my family will stay right here in the projects where we can afford it.”

- Do you personally know of people who have been displaced, if so, what happened?

- “Yeah, a lot of people got kicked out of their apartments. Miss Esther got put out about a year ago because the rent went up in her building over on Bradhurst. She had to go live with her son, somewhere out in Queens, I think. Mostly people who didn’t live in the projects already or have a lease had to move.”

Q. So do you think Harlem is better now or was it better back in the day when we were little?

A. “Oh it’s definitely better now, no doubt about that; but only cause all these White

people moved up here and are paying these high ass rents, but with that comes the better

looking blocks, all the stores, the banks, remember when we only had ManiHani?

(laughing) (Manufacturers Hanover Trust Bank that used to be only 1 of 2 banks in Harlem), all the police walking around now. It’s better for the kids and the old people. They feel safer now. It looks a lot nicer. The only thing is that by the time they decided to fix it up, it’s like we can’t even afford to really stay and enjoy it.”

Q. What do you think can or should be done in order to ensure that Black people stay in

Harlem?

- “Marsha, for real, I don’t know how that’s going to happen. I don’t think it’s gonna be

like all Black people are going to move out of Harlem, but there it’s definitely going to

more of a mixture of people now because it cost too much to live here, and who else can

afford to pay that type of rent or buy a brownstone for a million dollars? I think they

should’ve at least made it to where the rent stayed affordable for the people who already were living here. Just because you fixed up their building, you just going to kick them out now so somebody else can come in and pay $1300-$1400 dollars? That’s not right.”

Q. But aren’t there more jobs now in Harlem with all the new stores and businesses?

A. “Girl, don’t even let that fool you. Yeah, there are some more jobs up here, but mostly in

places like Duane Reade, Rite Aid, Starbucks, and places like that, but how’s somebody

supposed to afford to pay for an apartment working as a cashier in Duane Reade? Yeah, right! Those jobs for like teenagers or young people still living at home, but I don’t see where it’s no real jobs for people trying to pay people enough to live.”

Q. So do you think there should be more job training? education? I mean they can’t just hand

people high paying jobs if they’re not qualified, right?

- “No, I’m not saying that, like just give people jobs paying 50 and 60 thousand a year, but

at least make it to where if you’re gonna pay people only a little bit of money and then go around saying ‘oh, we gave out all these new jobs in Harlem’, then also let these same people live in Harlem at affordable rents that those compare with those salaries, feel me? Then, it’s a win-win situation, but if you just giving a person a job, a grown person and they can’t afford to pay their bills, how is that helping them?”

Q. What about other things in the community that have changed besides the housing – Do

you notice any difference with things like the schools? The hospitals? or even like the

parks?

- “Yeah, all of that has changed. Let me see, it’s a lot more schools now…a lot of those

charter schools. They seem better. The Frederick Douglas Academy teaches the kids Japanese and takes them on trips to Africa and stuff like that…my niece goes there. I definitely think the schools are better now compared to when we were coming up. They have all these computers and stuff now. The hospitals look better. They renovated Harlem Hospital a while back. It doesn’t look all dark now. I remember I wouldn’t take a sick dog there before! (laughing) but now, it looks good. I don’t know about the service. What else did you say? Oh the parks, well, I guess those are cleaned up, too. They built a lot those little jungle gyms and monkey bars and made them all colorful, it’s nice. I still go across the street to the Rutger (park) when they have the basketball games. It’s cool. Everything, for the most part, has improved so I guess that’s a good thing.”

Whoa!

“Just as the beautiful sound of her voice, reproduced by itself on the gramophone, would never console one for the loss of one’s mother, so a mechanical imitation of a storm would have left me as cold as did the illuminated fountains at the Exhibition. I required also, if the storm was to be absolutely genuine, that the shore from which I watched it should be a natural shore”

(Proust 546).

It was 7:30 a.m. on a warm, summer morning and as I walked to get a cup of coffee, I felt so strange because I was happy and sad at the same time. “What the hell is a Starbucks doing in Harlem?” I thought. Harlem, New York, the place where I grew up. Every time I go back to visit a family member or friend, I am absolutely amazed at all of the changes that have taken place in the community. It’s gone from a Renaissance in the 20’s and 30’s, to experiencing one of the worst hit communities of the crack era in the 80’s and 90’s, and now, to a rebirth of everything good that a community could ask for. Even Bill Clinton has an office in Harlem. It has become the place to be – to live, to work, to dine, to have good time! But there’s something else that has changed about Harlem, too – the faces. No longer are they just black or brown faces belonging to African Americans and Hispanics. There are people of all races - White, Asian, Mexican – it’s amazing. In New York, it’s the norm to see people of ethnic backgrounds. It’s one of things which makes the city so unique and special; but in Harlem, well, that was for the most part, a community where mostly black people lived. So as I strolled up the street, taking in the crisp, morning air, I was slightly taken off guard (even a little bewildered) to see a middle aged White man and a young girl who I assumed to be his daughter walk out of a building as I passed and just casually go towards the train station. They seemed very comfortable, very at ease, very at home – in Harlem. I watched them for a moment. It was, for me, a moment that defined what has happened in my community (although I don’t still live there, it will always be home for me). Things have changed, a lot. The streets are cleaner, buildings that sat burned out and abandoned for decades are now condominiums, small bodegas have been replaced by large chain stores like Pathmark, Duane Reade, and yes, even Starbucks. I’m happy that the community has finally taken a turn for the better. It put a smile on my face to see doorman saying “good morning” in front of buildings that were once buildings used as crack houses. And yet, as ironic (and crazy) as it might sound, I was sad. Sad for what has been lost in Harlem. The faces of the community, many of the people who had been there through the good and bad times, have had to move because they could no longer afford to live here. Some were brought out, others forced out. Many of those little stores that were staples of the community are also gone, forced to go out of business or sell their business because they too can no longer afford the new market rate. Most of all is the feel of the community that’s diminished. Sometimes, when all you have is each other, you band together and you learn to make the best of what you have no matter the circumstances. You take pride in beating the odds, in rising to the occasion despite not having the best of everything, and you build an inner strength and integrity from the wise, older people in your surroundings. You become like a close knit family. I don’t get that same sense of community when I visit Harlem now. Like the quote above, I no longer feel the community, as a whole, is as genuine as it used to be. It is a reproduction of its former self, as Proust stated, “a mechanical imitation”.

Holding On to Harlem

This is what we wanted, right? This is a part of “the rights” we felt we deserved, the inclusion we desired, the fair and equal playing field we demanded, right? Oh, wait a minute! Exceptions, you say? Well what might those be? Of course, there are some adjustments to be made, but that’s a part of the game. At least, this time, we’re players. Don’t be angry and hostile, sad and afraid, and close your mind, and your heart to the shift in the current. You can ride this wave, my friend.

Possessing economic power is key to having a voice in change and development. Nowhere does this hold more truth than in Harlem today. Without it, residents become voiceless spectators of change within their own community. Malcolm X understood this many years ago when in a 1964 speech he said:

“…we should own and operate and control the economy of our community.

You would never -- You can’t open up a black store in a white community.

White men won’t even patronize you. And he’s not wrong. He’s got sense

enough to look out for himself. You the one who don’t have sense enough

to look out for yourself. The white man -- The white man is too intelligent

to let someone else come and gain control of the economy of his community.

But you will let anybody come in and take control of the economy of your

community, control the housing, control the education, control the jobs,

control the businesses, under the pretext that you want to integrate…”

(Speech delivered April 12, 1964)

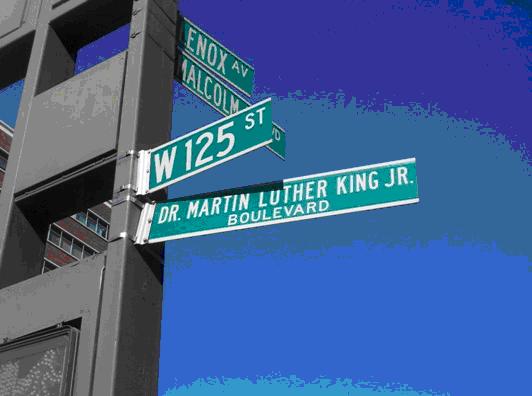

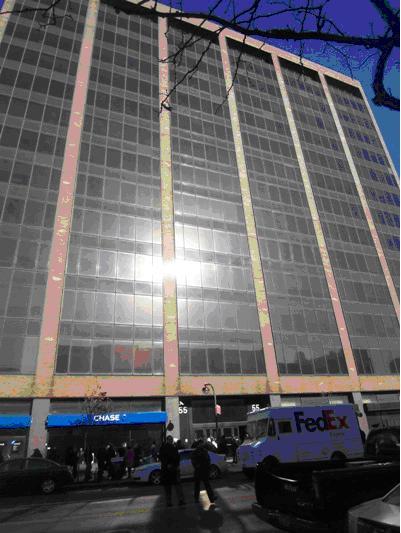

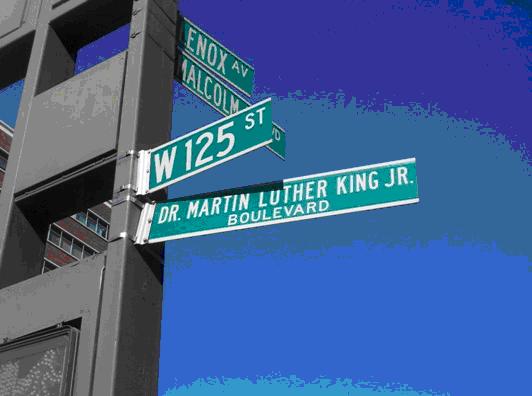

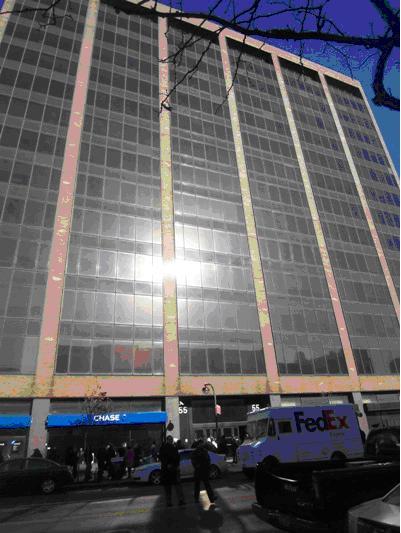

STAYING: Bill Clinton’s Office Building

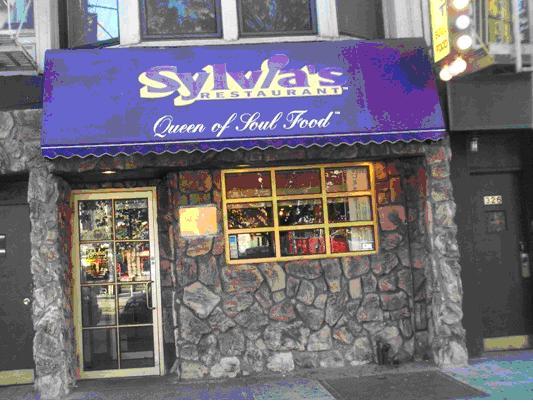

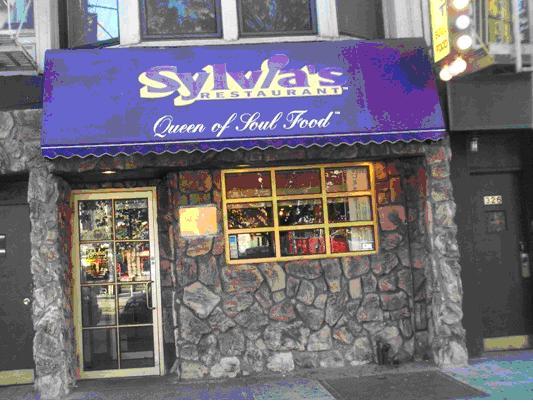

STAYING: Sylvia’s Soul Food, est. 1963

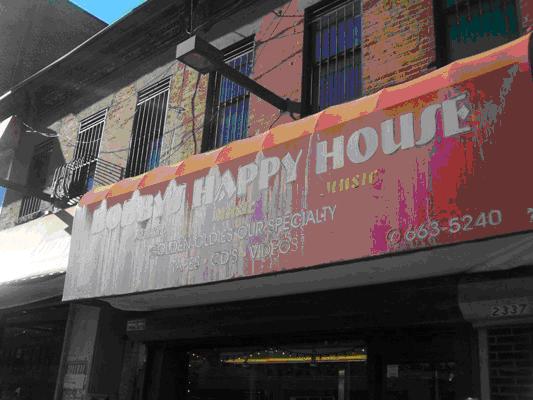

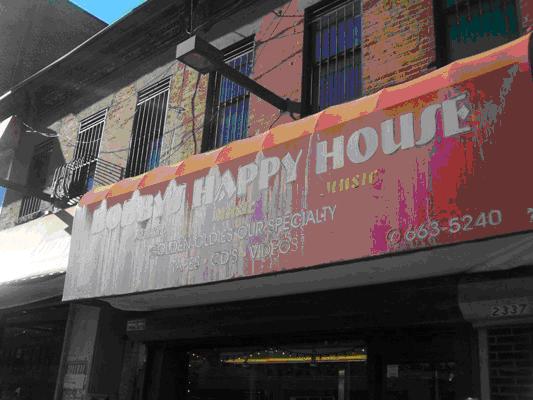

GOING - Bobby’s Happy House, est. 1946

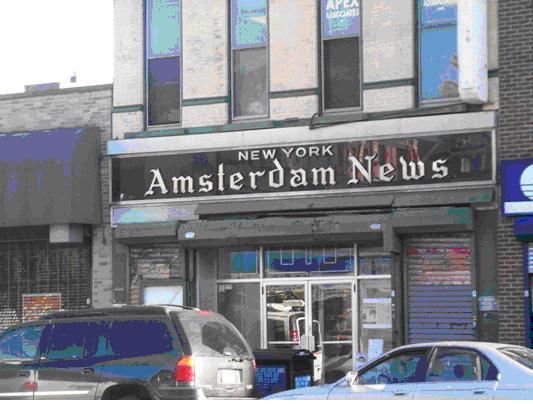

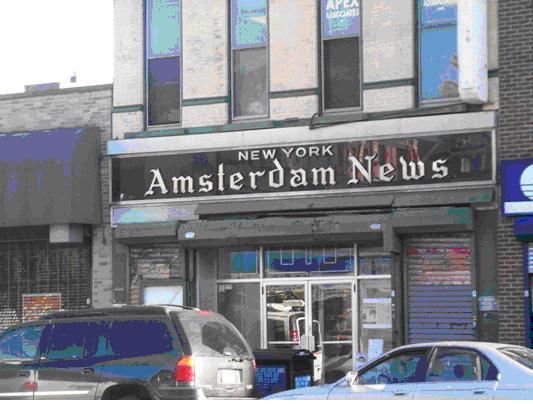

GOING - Amsterdam News Headquarters

“What does it take to make a journey? A place to start from, something to leave behind. A road, a trail, or a river. Companions, and something like a destination: a camp an inn, or another shore. We might imagine a journey with no destination, nothing but the act of going, and with never an arrival. But I think we would always hope to find something or someone, however unexpected and unprepared for. Seen from a distance or taken part in all journeys may be the same, and we arrive exactly where we are.”

(John Haines,"Moments and Journeys," The Norton Book of Nature Writing, 569).

And so the saying goes, “what is old is new again”…how appropriate in the case of Harlem, New York – which remains the epicenter of black culture. The only thing a bit off about that reference however, is that Harlem was never old to those who have lived there over the years; and only thing new about it are an influx of unfamiliar faces who believe it is they who have discovered something new! Harlem, the small neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan which stretches forty-five blocks long from 110th to 155th Streets, from the East River to the Hudson, has been home to a largely Black population since the early 1900’s. Throughout the years, Harlem residents have seen the neighborhood go from bad to worse and then slowly begin to transform into a busy, vibrant, gentrified area where outsiders no longer just want to come “sneak a peek” at the entertainment, cultural institutions, or dining establishments; but desire to live there as well - and are willing to pay top dollar to do so. It is a change that has brought mixed reactions amongst long time residents of the Harlem. For while some see the many changes as a welcomed addition to the community; there are those who feel that they are being pushed out of their homes and that despite staying in the area when times were not so good, they now won’t be able to enjoy the benefits that gentrification has brought about.

The works of literary giants such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston continue to influence and inspire today’s generation in Harlem, which is evident when walking down 125th Street and taking look on the table of the street vendors or walking into a bookstore. It is there one will find countless books written by African Americans, many right from the neighborhood. Walk into the Schomberg Center or The Studio Museum of Harlem and one will find testaments to the rich history and culture of Black culture, many of the items from the Harlem Renaissance era. These are just two of the institutions in the community that are normally filled with tourists, and those curious about Black culture, on any given day of the week. It’s really no different from the Harlem Renaissance when White people flocked to the area, out of curiosity, to watch Blacks perform in theatre or listen to them play jazz and blues.

The Apollo Theatre celebrated its 73rd birthday this year and continues to provide entertainment of the best and brightest new stars of today, just as it did back when newcomers (and now legends) such as James Brown, Billie Holiday, and Sarah Vaughn took to the stage. Another world class institution, The Cotton Club, remains on the same street where it opened in 1923. It continues to provide some of the best jazz and blues bands today as it did when Duke Ellington, Count Bassie, and Louie Armstrong played there. The difference today, however, is that anyone, not just White people, can attend and enjoy the shows there.

Recently the Harlem Armory underwent a multi million dollar renovation and re-opened its doors to provide tennis courts, sports and after school programs, and computer training for Harlem residents. It continues to house military personnel on one side of the facility. The significance of this building is that it was built back in the 1930’s for the first Black regiment to fight in World War I. The 369th Regiment became known across the globe as “The Harlem Hellfighter.” When the armory reopened in 2006, some of those veterans who are still alive were honored at a special ceremony. It goes to show that Harlem continues to recognize the contributions of its residents, past and present.

As during the Renaissance, Harlem social commentary continues to play a major role in the political arena. Long time Harlem resident Charlie Rangel has served in politics for over 30 years. Starting in the New York State Assembly and working his way up to recently becoming the chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, there is no doubt the Mr. Rangel was influenced by the early Renaissance pioneers such as W.E.B DuBois and Marcus Garvey. From Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (first African American elected to Congress) and Malcolm X to Percy Sutton (civil rights activist and former Manhattan Borough President) Reverend Al Sharpton, the voice of Harlem has been sustained since the early days of the Renaissance.

The nucleus of Harlem, and much of the Black experience, has always been the church. During the Renaissance, many Blacks came to experience a never before felt pride in who they were and what they had to offer. The church served as the hub where Blacks could express themselves freely through word and songs. It remains the same in Harlem today. Throughout the years, the churches have remained steadfast in the community, serving as the safety net and comfort zone of residents who may, at times, have felt abandoned by the rest of the world. So now, even in the face of Harlem’s restructuring, the church remains. Abyssinian Baptist Church is one of many famous churches in Harlem that people from all over come to worship at.

Abyssinian Baptist Church

From The Harlem Renaissance to the Harlem of 2007 not much as changed…the area, the people, the culture are as vibrant as it ever was. It may not have always been popular to admit it amongst other groups, but the Black experience has always been “in vogue”, influential, stylish, and different. The two eras simply prove that for all the changes over the years, the heart of Harlem remained the same.

New and Improved

Harlem has become the place to be – to live, to work, to dine, to have good time! But with new housing comes new residents and that has brought about another change in Harlem – the faces. No longer are they just black or brown faces belonging to African Americans and Hispanics. There are people of all races - White, Asian, Mexican – it’s amazing. In New York, it’s the norm to see people of ethnic backgrounds. It’s one of things which makes the city so unique and special; but in Harlem, well, that was for the most part, a community where mostly black people lived.

Harlem sets an example that people of different ethnic groups can live side by side in a community without having problems. path for the long haul, never abandoning the place they call home even when times went from bad to worse. The promise of a better day was always a distant thought, but no one could ever really imagine the changes that came about. The journey still continues…but the path for many has dramatically diverted. It remains to be seen whether or not they will remain on course.

Despite the vast improvements in Harlem, value for these residents doesn’t lie just in the exterior of new buildings, large chain stores, or a few new job openings in the area; the real value, for them, is maintaining the community’s identity and cultural heritage; and the only way to be able to do that is by continuing to have Black people live, work, build, and own within the community. Unless that happens, they feel, Harlem will become nothing more than a place where only the well-to-do can afford to live, a tourist haven, and a shell of its former self. This would, of course, be the fault of powerful developers, landlords, politicians, and greedy business owners all seeking to capitalize on the gentrified area without any real concern for the residents. In the words of Aristotle, “Fear is pain arising from the anticipation of evil” and it is this fear that many have expressed. So with each new, expensive high-rise, every new chain store that opens up, every old, familiar staple that closes, and less and less people looking familiar in the neighborhood, feelings of anger and resentment continue to fester, as change begins to feel like a personal attack. All of the improvements in the world don’t matter if they will no longer be able to remain in the community to enjoy it. “Beauty is an outward gift, which is seldom despised, except by those to whom it has been refused.” (Ralph Waldo Emerson)

Not everyone in Harlem feels that they are losing out. In fact, many would say that they have, in fact, gained much more than they could have ever imagined. For those who lived in the community in the 1980’s and prior, they can remember all too well when Harlem had very little choices as to where they shopped, banked, ate at a restaurant, or even were able to send their children to play. That has all changed as a result of gentrification. Millions of dollars in investments into the community have afforded residence an abundance of choices in those same areas and more. Not having to travel outside of the area in order to go to a nice restaurant or buy fresh food at the supermarket is great. Being able to go to a local hospital that is clean and offers quality service and care is a good thing - especially when just 10 or 15 years ago that very same hospital appeared as a dark and dirty facility with little staff and horrible service. For many people, however, some of the best things about the re-building of Harlem are the safer streets and new parks. For them it means a place where their children can play, their elderly parents can sit outside and enjoy a nice day, and where they themselves can go to have a picnic or barbecue. Change, they see, is a good thing for Harlem; and it doesn’t mean that residents have to leave – they simply have to figure out a way to stay. “You're either part of the solution or part of the problem.” (Eldridge Cleaver, speech given in San Francisco in 1968)

Many Harlem residents also welcome the change in ethnic diversity. They take pride in

knowing that others now want live in “their’ neighborhoods. They’re happy that others have come to appreciate Harlem, its residents, and what the community has to offer. The diversity is positive for everyone, to be able to live together, and respect each other.

Harlem residents find that improvements and changes are far reaching in many other aspects as well. With a healthcare crisis that has been the center of national attention for several years, Harlem has finally been able to begin improving much of its medical services, provide more options for patients, and undertake long overdue renovations to local hospitals. Due in large part to gentrification, new residents (with higher incomes) expect quality service. As such, funds for more clinics, larger staffs, and new hospital units to focus on areas such as asthma and HIV and AIDS. Harlem long suffered from budget cuts and closing medical facilities that simply could not compete with the growing number of private practices and better funded hospitals. Many residents were often shunned or outright refused medical treatment because they either didn’t’ have coverage or had only a lower form of coverage with Medicaid or Medicare. That is all changing now, as new social service facilities, literature, and community advocates are educating residents on how and where to go within the community to receive the care they need. Long time standing institutions including Harlem Hospital, North General, and St. Luke’s have received grants, city and state funding to improve healthcare.

Interview

Marlene Taylor PA, practitioner - 25 years

Primary Care Provider at North General Hospital

Harlem, New York

Q. What, if any, changes have you seen in Harlem over the past 10-15 years, in terms of the quality of care provided for residents? Has it gotten better? worse? and to what would you attribute those changes?

A. As a health care provider in the community, access to pharmacies has always been a concern, as a shortage was a problem for some time (1985-1995).

Over the past 10 years, there has been an increase in the number of pharmacies in the inner communities, particularly between and 7th and Convent Avenues. In addition, commercial pharmacies such as Duane, Rite Aid, are noticeable in areas where they previously were only in “better areas.”

The housing (high risers with doorman buildings) are seen where they were not seen before.

Schools (charter schools) and the ethnic mix and residents is changing. More diversity with an increase in Asians and Caucasians.

The access to the pharmacies is an improvement, however if the owners of these businesses have respect and are culturally sensitive to the community residents, then it is an improvement. Overall I would have to say it is.

Q. With an influx of new residents in Harlem, how has that impacted medical service in the community?

A. I would have to say that I have not noticed an increase in patients in the clinic solely because Harlem is changing. I think that newer resident probably still keep their private doctors in other areas of NY (i.e. lower Manhattan). Because the hospital I practice in is a community based hospital, it has been a historic landmark for older African Americans who have lived in the community for decades. My specialty for example is one that has issues which may prevent those who live right her to come into the clinic unless it is an emergency.

Q. Do you find that the patient population is more diverse now than a few years back?

A. It is slightly more diverse. Moreso with Latinos - I have Brazilian, Mexican, Portuguese, and a patient from Uruguay. I also have more African patients (Mali, Ghana, Senegalese).

I do have a new Russian patient, too, however she does not live in the community. She commutes from lower Manhattan

Q. What has been the disparity between healthcare in Harlem versus healthcare in other parts of Manhattan like, say for instance at Lenox Hill Hospital or Mt. Sinai? Has any of that changed recently?

A. There have been more satellite clinics opening up which are affiliated with the larger hospitals. People of color have traditionally used the ER for primary care and have not been compliant with appointments. The approach to dealing health care problem, has been to open up more primary care centers so that they will follow up more regularly and prevent the diseases which tend to bring them to the ER in a crisis. The jury is still out as to whether or not these sites are being underutilized. Patients who go to hospitals like Lenox Hill and Mt Sinai tend to use private offices as opposed to hospital based clinics. I have noticed a few private offices opening up in Harlem over the past 5 to7 yrs which had not been there before. In addition, certain specialty offices, like cosmetic surgery / plastic surgery offices, are seen in central Harlem. This speaks to more middle class residents who can afford to pay for some of these medical subspecialty services.

In terms of buying, Harlem has always been a force to be reckoned with when it comes to economic purchasing power; and more retailers have come to realize this over the past decade. Within Harlem, there are “sub communities” that encompass West, Central, and East Harlem. It also includes the areas of Washington Heights and Inwood. In total, approximately 544,000 people reside in Harlem alone, with a reported $5 billion dollar annual income, and an estimated $2 billion dollar purchasing prowess. As gentrification continues to diversify the population, increase the community’s dollar value and spending, it has become a very attractive community for retailers. Harlem has seen stores including Disney, Old Navy, Magic Johnson Theatre, H&M, and even Starbucks land in its neighborhood. In addition, every major banking institution has moved into the community as well, many opening more than one branch within just a few

blocks of each other.

As during the Renaissance, Harlem social commentary continues to play a major role in the political arena. Long time Harlem resident Charlie Rangel has served in politics for over 30 years. Starting in the New York State Assembly and working his way up to recently becoming the chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, there is no doubt the Mr. Rangel was influenced by the early Renaissance pioneers such as W.E.B DuBois, who founded the NAACP, and Marcus Garvey, who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL). From Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (first African American elected to Congress) and Malcolm X to Percy Sutton (civil rights activist and former Manhattan Borough President) Reverend Al Sharpton, the voice of Harlem has been sustained since the early days of the Renaissance.

Harlem Forever

“It is the excitement of becoming - always becoming, trying, probing, falling, resting, and trying again- but always trying and always gaining...”

(Lyndon B. Johnson, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1965)

Harlem is finally becoming the community it was meant to be - the type of community that most people would be proud to reside in - a community with beautiful homes, safe, clean streets, good schools, cultural institutions, plenty of retail stores and supermarkets, entertainment venues, restaurants, and a diverse population. Unfortunately, for some, the journey of becoming was paved with a path of fear and frustration to go hand-in-hand with the changes. Low income, lack of education, minimal job market skills, and missed opportunities to purchase property are a few of the causes which now threaten the very core of what makes Harlem, well…HARLEM – the people! If the ethnic makeup of Harlem becomes a majority of any other race besides African American, there is little doubt that the cultural fabric of the community will be diluted and, perhaps, eventually fade into nothing more than a reference of an era gone by.

Gentrification doesn’t have to be the enemy of any community unless it makes changes within in a community and does not take into account how those changes will affect residents. In order for the process to work out fairly for everyone, all parties must first be willing and open to a number of actions including: assessing the community’s situation, the goals of developers, and the needs of residents.

The reality is that there are quite a number of valid reasons given by those who are both for, and against, gentrification. As such, there have been various meetings conducted by politicians, community activists and organizations, developers, and residents in attempts to find common ground in which everyone benefits. This paper strives to offer solutions relating to key issues of concern regarding gentrification, the likelihood of the those solutions, various options to which residents can refer that may enable them to empower themselves, and, finally, implications for policy makers regarding gentrification in Harlem. When taking a look at all of the factors involved, it becomes increasingly clear that finding solutions to please all parties is not quite as clear cut as one may assume.

If “Gentrification in Harlem” were a made-for-television special, the finale would probably end with some multi-millionaire “good guy” coming in to save the community at the 11th hour, the “bad guy” developer having a sudden change of heart about evicting tenants, and the angry, defiant residents realizing that working together for change can be a good thing. As the credits roll, everyone would be smiling and all the issues which dominated the first 80 minutes of the movie were somehow miraculously fixed in the last 10! Unfortunately, that’s not going to happen for the real life situation in Harlem. So what can be done?

Well, for starters, it would be nice to see rich African American pool their money together and buy real estate in Harlem to ensure black owned businesses and affordable housing remain. It is reported that Bill Cosby’s net worth is $540 million dollars, Magic Johnson - $900 million, Sean “P Diddy” Combs - $300 million, Sean “Jay Z” Carter - $547 million, Moguls Damon Dash and Russell Simmons - $325 and $200 million respectively, and billionaires, Oprah Winfrey - $1.3 billion, and Bob Johnson - $1.1 billion (Forbes). While only Damon Dash was ever a resident of Harlem, the others noted certainly owe a debt of gratitude to Harlem as it paved the way for Blacks all over the world during the Harlem Renaissance. Certainly, any performer or African with high profile status has been to The Apollo Theatre, eaten at Sylvia’s restaurant, or walked down 125th Street just to experience the culture. Surely, no African American entertainer, athlete, sports star, politician, or dignitary has ever been to New York and not been to Harlem. It holds far too much value in the history for the African American race. In that vein, it should not be a second thought for African Americans with a net worth of $100 million dollars, and up, to invest in the Harlem community by purchasing real estate, developing affordable housing, by contributing to schools, and opening black owned businesses. Recent developer Kimco Realty, purchased one block in Harlem for $50 million dollars and plan to evict business owners in order to make way for new retail stores and a hotel. Surely, Jay Z, P. Diddy, and Damon Dash can pool together $50 million to buy another block. Likewise, Oprah and Bob Johnson could simply buy one (or two) blocks each…and not even miss the cash. If not the entire block, then, perhaps, just purchasing a few of the buildings on various blocks. Once doing so, allow long time small businesses to remain or, if they must relocate, allow them to do so within the community at an affordable (not market) rate. New residential buildings could guarantee a certain percentage of affordable housing to existing Harlem residents, while buildings that were rehabbed would negotiate fair, and affordable, rents for existing tenants, perhaps offering rent stabilization.

Another possible solution would be forming an alliance between local business owners and developers might prove a win-win situation for not only them, but for the community at large. First, business owners would agree to employ a certain number of qualified people who have applied to live in a particular building and pay a fair wage. Then, the landlord would agree to reduce the market value rent for the unit and adjust it according to their salary. Rent would be automatically deducted from the resident’s paycheck and sent directly to the landlord. Business owners would have staff members who would be dedicated to work because their housing depended upon it; landlords would be guaranteed rent payments; and residents would be employed and able to stay in the community. It would be the “invisible hand” in full swing.

Real estate developers should work with long time, local Black owned businesses. The fabric of Harlem is its culture, which derives not only from the entertainment, fashion, and restaurants; but from stores such as Bobby House House, the 1st Black owned business in Harlem. It opened in 1946 and will be forced to close in 2008, taking with it a piece of Harlem’s history and soul. Developers can still be creative and build in the community without having to recreate it. Some things should be left alone. Market rent should not apply to these institutions. There aren’t an abundance of these businesses, so what few are left, should be allowed to remain.

What better way to ensure that minorities are able to stay in their communities than to train them in the business of development and management? If one is trained by top professionals in any field, the likelihood is that that person will become very good at whatever that trade is. For every real estate developer who wants to go into Harlem and buy of swaths of property, there should be a mandate which requires them to have programs which will take in a number of residents, particularly younger residents, who will learn the business of development and ownership. The more residents who begin to learn, and understand the process, the more information will filter throughout the community and thus, inspire people to become more involved in taking a greater responsibility towards being involved in the process.

Section 8 is supposed to provide a helping hand to low income people by paying a portion of rent directly to landlords. The policy has gone awry and many landlords refuse to even accept Section 8 tenants anymore. The criteria for receiving Section 8 should be revised so that anyone receiving aid should only be eligible for a certain amount of time and proof of employment should be verified on a regular basis. Landlords should be offered tax incentives to accept Section 8 since they are not required to accept the vouchers, but if they receive the incentives they should be subjected to inspections to ensure that they are maintaining the properties. There should also be a certain number of Section 8 properties allowed on each block to ensure diversity.

The answer to gentrification isn’t an easy one for some do not view it as a problem in the first place. Perhaps the most important topic of discussion revolves around the criteria used to determine whether gentrification can truly, and fairly, be considered a success or failure. I suppose that depends on who you speak to. There are no easy answers, and in the end, everyone won’t be pleased. Nonetheless, all potential solutions merit further exploration as every community deserves to thrive and those residents who have hung in there through good and bad times, certainly deserve to enjoy the success.

The journey that the Harlem community has been on throughout the years has certainly had its shares of ups and downs. Some would argue more “downs” than “ups”. From the heyday of The Harlem Renaissance when Blacks first migrated from both the South and the Caribbean to settle in Harlem, and the world first took notice of, acknowledged, and showed appreciation of their culture; to the era of drug infestation and being an underserved community; to the current state of restored brownstones and hi-rise coops, Harlem continues to prove resilient.

For those who are having a hard time dealing with the changes in Harlem, it might be wise that they first, keep the focus on finding a way to ensure that they stay in the community. In order to effect change in the community, it’s important to remain there. Forming community groups, being active within the community, and most of all, being informed, will serve to help residents become more a part of the transition process – and help others to do so as well. For those who welcome the changes, they too should become active, educated, and informed about what is happening in Harlem. Patronizing Black owned businesses in Harlem, exploring ways to open up new businesses, and buying homes are just a few of the ways in which all residents can do their part to help maintain Harlem’s cultural integrity. Being open to change is important as well for change is inevitable.

Yes, those old buildings are all fixed up now. Co-ops. Condominiums. Townhouses…they look real nice. I could’ve never envisioned it. Those little stores are gone, too; but hey, at least there is more variety from big chain stores and supermarkets. The streets are brighter now, too (finally fixed those lampposts)…and a whole lot cleaner. I think it’s a good thing to see police officers patrolling the streets and not just coming around because something bad has happened. It looks so different now, everything, even the people. Where did they come from? I know some think it’s because of them that all of these changes have come about; but so what? We all benefit. We deserve the clean streets, nice buildings, safety, and nice shopping areas. Sure the cost of living here has gone up tremendously, but it’s costly everywhere! Would they rather have the neighborhood remain underserved and disadvantaged just to keep the rent a little lower, while also keeping the abandoned buildings around even longer? We’ve fought the good fight for so long just to be equal, included, level the field. So we’re finally gaining a few perks. Why do some people feel like something is wrong? Well…I guess it is a little strange to feel like in order for those things to happen, we had to give up something that can’t quite be described. Weren’t we all, just as we were, deserving of better anytime before now? I suppose that’s just how economics go. We have to change with the times…or the times will change anyway and leave us behind. Yes, my friend, I’m still working it all out in my head, too. Trying to grasp the new look, sound, and feel of home. But we can do it. Together, we can do it.

This is what we wanted, right?

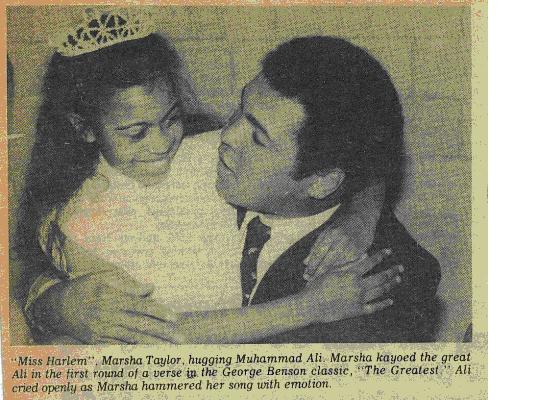

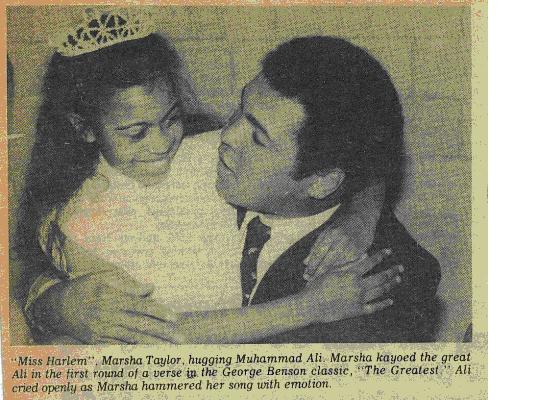

Author, Marsha Taylor, “Little Miss Harlem”

with Muhammad Ali in Harlem in 1978

Works Cited

"A History of Harlem." Mount Morris Park Community Improvement. 2002. Mount Morris Park Community Improvement Association. 24 Nov. 2007 <http://www.harlemmtmorris.org/history.htm>.

Beasley, Marcus. "Gentrification Gone Mad!" New York Amsterdam News 02 Aug. 2007: 3. ProQuest. New York. 19 Nov. 2007.

Berstein, Emily M. "A New Bradhurst; Harlem Trades Symbols of Decay for Symbols of Renewal." New York Times 06 Jan. 1994. 07 Oct. 2007 <http://www.nytimes.com>.

"Black Harlem Once Was News." Harlem History. 2005. Columbia University. 21 Oct. 2007 <http://www.columbia.edu/cu/iraas/harlem/neighborhood/neighborhood.html>.

Cooke, Sam. "A Change is Gonna Come." Rec. 21 Dec 1963. Ain't That Good News. RCA, 1964.

Courbould, Clare. "Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem." Journal of Social History 40 (2007): 859-894. Proquest. New YOrk. 18 Nov. 2007.

Craig, Leonard J. Personal interview. 19 Nov. 2007.

Diaz, Eileen. Online Interview. 14 Nov. 2007.

Ellis, Edward Robb. The Epic of New York City. New York: Kodansha America, 1997.

Foderaro, Lisa W. "Harlem's Hedge Against Gentrification." The New York Times 16 Aug. 1987. 23 Sept. 2007.

Freeman, Lance. There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification From the Ground Up. Philadelphia, PA: Temple UP, 2006.

Greenberg, Cheryl. "The Politics of Disorder: Reexamining Harlem's Riots of 1935 and 1943. " Journal of Urban History 18.4 (1992): 395. Research Library. ProQuest. New York: 2 Dec. 2007 <http://www.proquest.com/>

Hackworth, Jason. The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism. Ithaca, New York: Cornell UP, 2006.

Haines, John. Moments and Journeys in The Norton Book of Nature Writing. Finch, Robert, and John Elder. College ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1990. 1-1135.

Hampton, Angela M. Personal interview. 13 Nov. 2007.

"Harlem." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 4 Dec 2007. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 9 Dec 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Harlem&oldid=175719509>.

"Harlem Renaissance," Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2007

http://encarta.msn.com © 1997-2007 Microsoft Corporation.

"Harlem Renaissance." Online NewsHour/PBS. 20 Feb. 1998. Public Broadcasting Service. 9 Dec. 2007 <http://www.pbs.org/newshour/forum/february98/harlem1.html>.

"History of Harlem." Welcome to Harlem. 2005. 02 Dec. 2007 <http://welcometoharlem.com/page/harlem_history/>.

Johnson, James Weldon. The Future Harlem in The Selected Writings of James Weldon Johnson, Vol. 1: The New York Age Editorials (1914-1923). Wilson, Sondra Kathryn, ed.. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995, 100-101.

Johnson-Grant, Thelma. Personal interview. 1 Dec. 2007.

Jones, Rickey. "Harlem Under Seige." Network Journal 8 (2001): 7. Proquest. New York. 04 Nov. 2007.

Kuchment, Anna. "Coming Home to Harlem; with Clinton's Arrival, the Area Synonymous with Black Culture is Going Upscale--and Fighting for Its Soul." Newsweek 13 Aug. 2001, International ed.: 44. ProQuest. New York. 21 Oct. 2007.

Lee, Li Way. "Estimating Earnings in an Information-Poor Market: the Case of Crack Cocaine." The Journal of Socio-Economics 28 (1999): 289-294. New York. 9 Dec. 2007 <http://http://www.sciencedirect.com>.

List of Mayors of New York City." Wikipedia. 14 Dec. 2007. 9 Dec. 2007 <www.wikipedia.com>.

Little, Rivka G. "The New Harlem - Who's Behind the Real Estate Gold Rush and Who's Fighting It?" The Village Voice 18 Sept. 2002. 23 Sept. 2007.

Maurrasse, David J. Listening to Harlem: Gentrification, Community, and Business. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: Routledge, 2006.

Miller, R. Baxter. "Baptized Infidel: Play and Critical Legacy." African American Review 21 (1987): 393-414.

Palen, J. John, and Bruce London. ". Gentrification, Displacement and Neighborhood Revitalization." Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 6 (1987): 256. New York. 23 Sept. 2007.

Proust, Marcel. Swann’s Way. Vol. 1. New York: The Modern Library, 2003. 1-611.

Rampersad, Arnold (2003). “The Book That Launched the Harlem Renaissance.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, (38), 87. Retrieved December 1, 2007, from Ethnic NewsWatch (ENW) database.

Rancine, Theresa. "Doing Business in Harlem." Network Journal 14 (2006): 8. Proquest. New York. 21 Oct. 2007.

Robinson, Lisa Clayton, and Tanu T. Henry. "New York’s Harlem.” Footsteps 1 Nov. 2005: 30-33. Research Library. ProQuest. 2 Dec. 2007 <http://www.proquest.com/>

Ryan, Maureen, and Walter Dean Myers. "The Harlem Renaissance. " Scholastic Action 7 Feb. 2005: 14-16. Research Library. ProQuest. 2 Dec. 2007 <http://www.proquest.com/>

The Sugar Hill Gang. "Rapper's Delight." By Guy O' Brian, Michael Wright, Henry Jackson. Rec. Oct. 1979. The Sugar Hill Gang. Sugar Hill Records, 1979.

Taylor, Charles. Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1994.

Taylor, PA, Marlene. Personal interview. 9 Nov. 2007.

Thomas, Alexander R. "Harlem Between Heaven and Hell." Contemporary Sociology 33 (2004): 212-213. Proquest. New York. 04 Nov. 2007.

Wintz, Cary. Harlem Speaks: a Living History of the Harlem Ranaissance. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks MediaFusion, 2007.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1950.

Wright, Keith. Interview with Gil Noble. Like It Is. WABC. Channel 7, New York. 21 Oct. 2007.