Joseph Baide

December 2007

The Art of Sexual Power

Sex is perhaps the most visceral of all organic phenomena due to its unexplainable yet all-encompassing influence over us. It is this influence that proves so frightening to us because we are so utterly helpless against it. Power and sex are inexorably linked. It is our nature to attain power; sometimes through sex, sometimes through force. We are helpless to our sexual nature and vulnerable to that which stirs a sexual response in us. In the male dominated Western culture, sexual power motivates and informs the world around us, everything from art to politics. Representations of sexual power in American media illustrate the struggle for power between the genders. Men attain power by taking control over the sexual power women have over them, while women possess power by claiming their sexuality from men. This tug-of-war pattern is evident in our culture’s historical figures. Feminist scholar, Camille Paglia, examines the relationship between sex and power by looking at the impact of these historical figures on our culture’s views of sexual power. In the works of figures such as Madonna – perhaps the most influential arbiter of sexual power in modern times – we are witness to a new art form: the art of sexual power.

In Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia suggests that Western Culture and its literature, art, and political and religious institutions represents men's fear of women and the mysterious power they hold within their vaginas. "Sex is a far darker power that feminism has admitted. Sex is the point of contact between man and nature, where morality and good intentions fall to primitive urges." Paglia theorizes that it is in our nature to conquer the potential power that women have over men. The penis, unlike the vagina, is external and visual and therefore can be measured, compared, and examined while the vagina is hidden, mysterious, and without a measurable shape. "Man is condemned to a perpetual pattern of linearity, focus, aim, directedness. Woman's eroticism is diffused throughout her body." The male ego is a sexual persona and by controlling women, men are attempting to control nature, making them immeasurably powerful. According to Paglia, Western culture is the manifestation of that quest for power. "Men, bonding together, invented culture as a defense against female nature."

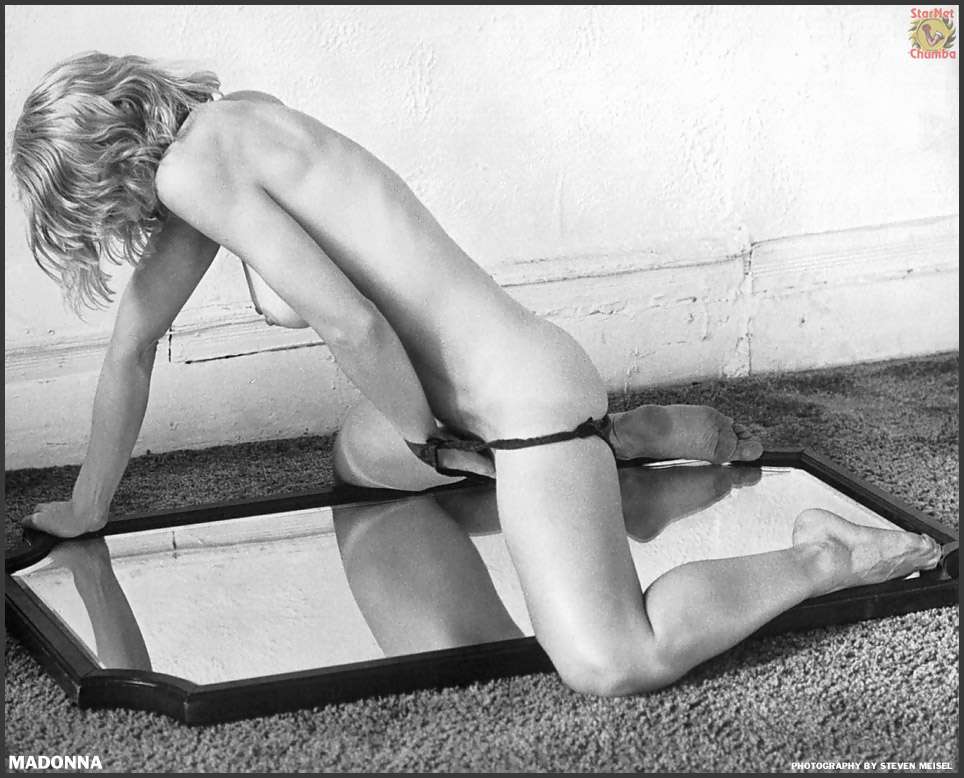

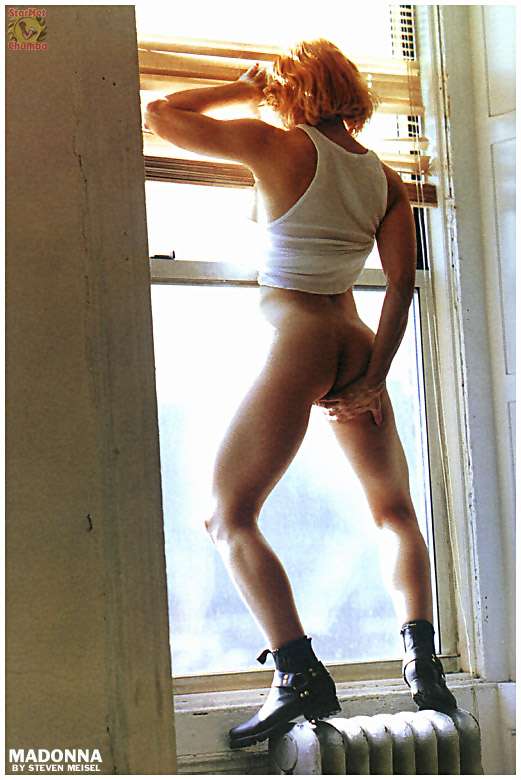

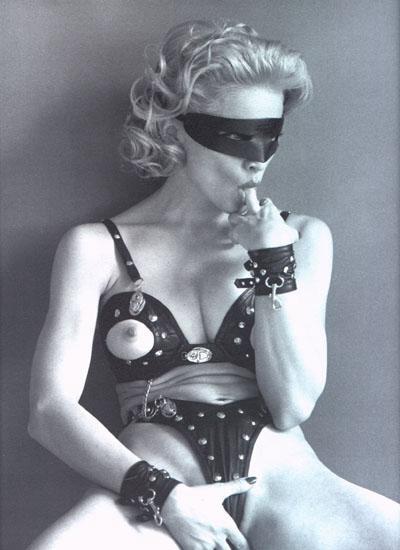

It appears as though Madonna’s entire career was based on a single motivation: to reclaim her sexual power from the hegemonic power of men. In 1992, she released a photo-essay titled “Sex.” Her introduction clearly established the context for the collection of erotic images. She set out to document her sexual fantasies, as a means to commiserate with the viewing audience over things previously considered shameful and subversive. Women have sexual fantasies just the same as men, and they have the right to express them and realize them just the same as men. It was Madonna’s objective to reclaim her own sexual identity and gratification and separate it from the sexual gratification of men. In the images, Madonna plays characters of her own sexual fantasy world. Sometimes she is dominated or objectified, but she is always the architect of the fantasy. If it is her will to be objectified, she allows it so as to fulfill her own sexual fantasy, and not the sexual fantasy of a man.

In an interview for a network program, “Nightline,” Madonna answered charges that images of her being chained by a neck manacle and crawling on the floor like a cat in an earlier video, "Express Yourself," she unwittingly condoned the "degradation" and "humiliation" of women. Madonna said: "But I chained myself! I'm in charge." In a New York Times article, Paglia calls Madonna “the true feminist... who exposes the puritanism and suffocating ideology of American feminism. Madonna has taught young women to be fully female and sexual while still exercising total control over their lives. She shows girls how to be attractive, sensual, energetic, ambitious, aggressive and funny -- all at the same time. She sees both the animality and the artifice. Feminism says, ‘No more masks.’ Madonna says we are nothing but masks.”

Although Madonna’s feminist attitude toward sex is admirable, it raises an interesting paradox between sex and power: To what extent does the sex act require one to relinquish power? Madonna’s career has been based on the principle that she is in full control of her career, her sexuality, and her image. Her control over her business and her art is evident which made the Sex project puzzling since sex is act of letting go, not of domination. In sexual acts of sadomasochism and domination, the person being dominated is the one experiencing sexual pleasure. It is the dominated that reaches climax because he/she is being humiliated or tortured. The dominator provides the pleasure but does not reach orgasm by the act of dominating. The sexual fantasies explored in Madonna’s photo essay were aborted at the moment of climax. We see her pleasuring herself, or recreating a moment in which she receives sexual gratification from another, but the construction of those moments truncates the climax. It is Madonna’s control of the situation and her creation of a product that prevents the outcome from being truly sexual. As a result, the audience is not a voyeur but instead the consumer of a product. For Madonna to truly be sexual, she must give in to the act and relinquish power – something that goes against her nature and will likely never do in front of the camera.

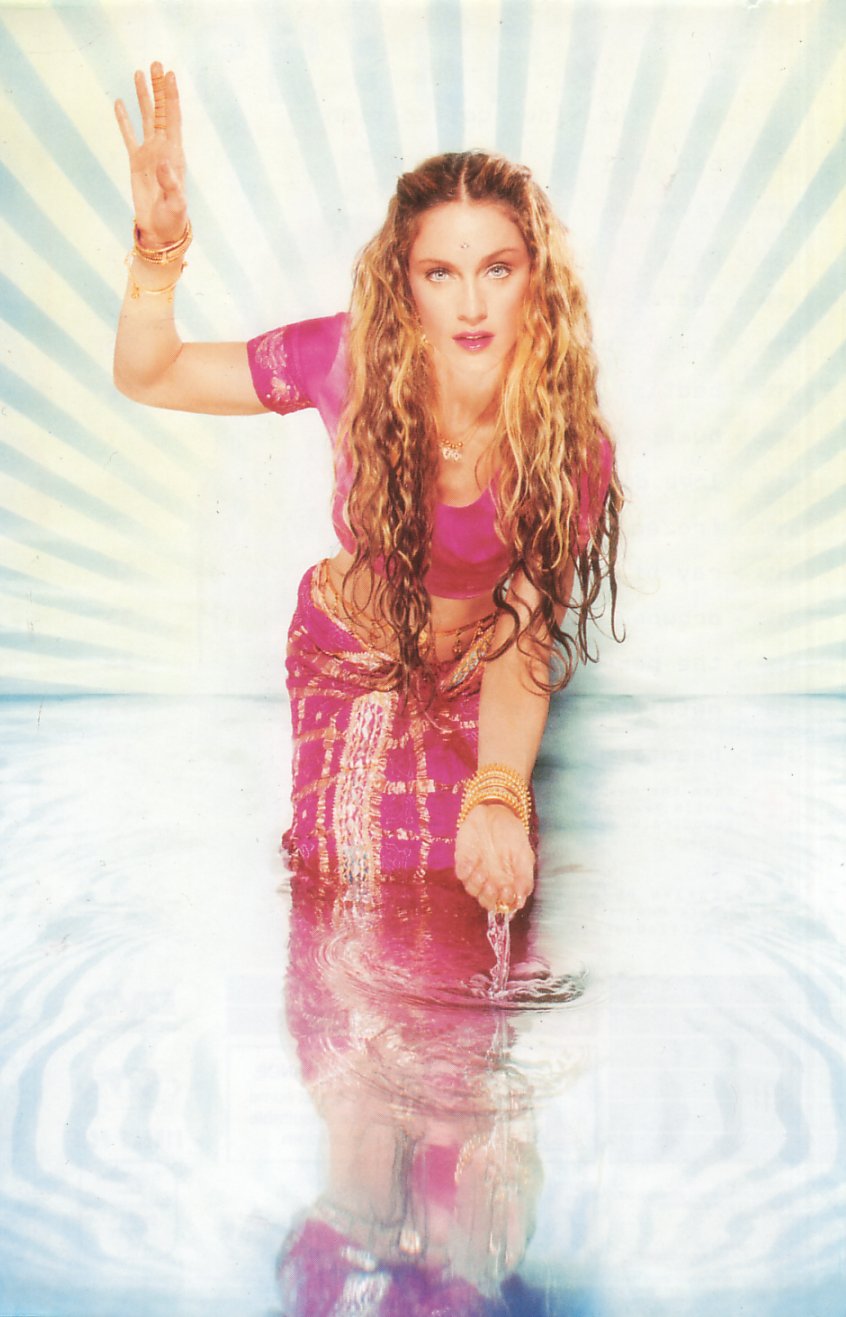

No, Really… Who IS That Girl?

From the East Village street urchin to virgin bride, from peep show stripper to spiritual mother, from dominatrix to Hindu goddess, Madonna has personified all of these images and more. To the general public it appears as though Madonna – the person – takes on these images in a calculated attempt to maintain relevance in a fickle marketplace. Yet Madonna – the artist – has always considered herself a performance artist, a self-described appropriator of cultural references, highbrow art, and international religions. Her image is her art; she is the canvas onto which she paints a multimedia portrait. The general misconception of her is that her various images are simply marketing tactics to sell her lowbrow music. I personally don’t think it is that simple. To believe this version of Madonna is to discredit her longevity and success across demographics and global cultures. According to the Guinness Book of World Records Madonna is the best selling female artist of all time with over 250 million records sold worldwide. And to those who have questioned her relevance in modern popular culture, they need only look at her latest entry in the Guinness Record Books: her 2006 Confessions World Tour was the highest grossing concert tour by a female artist of all time with almost $200 million in ticket sales. Could anyone achieve such success by simply being a clever businesswoman and marketer? Certainly her art has connected with the public in a profound way. Another misconception is that her success is driven by sex and controversy. Without question, these elements are part of her formula, but again, the secret to her success is much more complicated than simply scandal. On the other hand, it would be inaccurate to attribute her success and longevity to her music alone. While she has certainly made an indelible mark in contemporary American popular music, her primary talent is not that of a singer or composer, but instead of conductor of an all-encompassing orchestra that includes the visual, the audible, and the sensorial. She immerses herself completely in a concept, from image to sound, from persona to performance. What the audience sees is the character in Madonna’s latest production. It is this kaleidoscope of images and personae (different from the person) that keeps her interesting to the public. The audience never sees the woman behind the mask so they never get bored. All we know of Madonna is that she is an imposing person with control over her product and with feminist inclinations. We know only what Madonna wants to reveal of herself, which begs the question: What is behind the mask? The answer is most likely a narcissist.

Christopher Lasch’s definition of narcissism is strikingly fitting to what we know of the woman behind the mask. "The new narcissist is haunted not by guilt but by anxiety. He seeks not to inflict his own certainties on others but to find a meaning in life. Liberated from the superstitions of the past, he doubts even the reality of his own existence. Superficially relaxed and tolerant, he finds little use for dogmas of racial and ethnic purity but at the same time forfeits the security of group loyalties and regards everyone as a rival for the favors conferred by a paternalistic state. His sexual attitudes are permissive rather than puritanical, even though his emancipation from ancient taboos brings him no sexual peace. Fiercely competitive in his demand for approval and acclaim, he distrusts competition because he associates it unconsciously with an unbridled urge to destroy. Hence he repudiates the competitive ideologies that flourished at an earlier stage of capitalist development and distrusts even their limited expression in sports and games. He extols cooperation and teamwork while harboring deeply antisocial impulses. He praises respect for rules and regulations in the secret belief that they do not apply to him. Acquisitive in the sense that his cravings have no limits, he does not accumulate goods and provisions against the future, in the manner of the acquisitive individualist of nineteenth-century political economy, but demands immediate gratification and lives in a state of restless, perpetually unsatisfied desire." Madonna could be considered Lasch’s prime example of narcissism: fiercely competitive, seeking meaning in life through her art by appropriating dogmas, and just as quickly discarding them, sexual permissiveness which has been interpreted by some as female sexual liberation. It would seem that her art is driven by her narcissism. Yet it is interesting that her narcissism drives her to put on masks rather than exposing more of herself to the public.

Madonna is seemingly empowered by her liberated points of view toward sex and gender. Most of her art takes on a feminist approach to women’s sexual liberation as in her Sex book, which sought to level the playing field of sexual fantasy and exploitation between men and women. It was her overwhelmingly direct affront on American mores that created the 1992 backlash against her. Lasch said that “Whereas the resentment of women against men for the most part has solid roots in the discrimination and sexual danger to which women are constantly exposed, the resentment of men against women, when men still control most of the power and wealth in society yet feel themselves threatened on every hand - intimidated, emasculated - appears deeply irrational, and for that reason not likely to be appeased by changes in feminist tactics designed to reassure men that liberated women threaten no one… there is not much that feminists can say to soften the sex war or to assure their adversaries that men and women will live happily together when it is over.” Not only did Madonna challenge the ideology of sexual women, she defied the unwritten rules of celebrity when she exposed herself to the media instead of being exposed by the media.

Her exposure, however shocking, was superficial in its contrivance. In Sex, Madonna took on the character and persona of Dita Parlo, a 1930’s silent film actress. Through Dita, Madonna played out sexual fantasies in her writing and in still photography. Had she exposed herself in a moment of vulnerability and true sexual climax, she might have exposed something of the person behind the character, but the viewer is never given more than the tease of gratification, leaving them wanting – and wondering – more. Today’s Madonna is more age-appropriate as she explores highbrow themes of religious imagery, social causes such as poverty and adoption, and children’s books. Lasch says that 'our society notoriously finds little use of the elderly. It defines them as useless, forces them to retire before they have exhausted their capacity for work, and reinforces their sense of superfluity at every opportunity." It will be interesting to follow the next act of Madonna’s performance if only to see what characters she will take on in her attempt to defy the inevitable obstacle of age.

Narcissism Is Only Skin Deep

In the preface to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the author’s preface states: “The artist is the creator of beautiful things. To reveal art and conceal the artist is art's aim. The critic is he who can translate into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful things. The highest as the lowest form of criticism is a mode of autobiography. Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault. Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom beautiful things mean only beauty.”

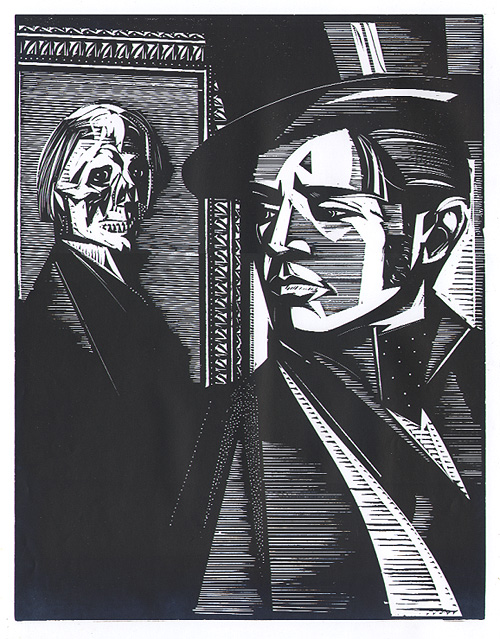

Wilde sets the stage for the themes he would explore in his masterpiece, specifically the concept of beauty. Wilde’s character, Dorian Gray, becomes obsessed with beauty as he seeks it through his interactions with Sybil Vane whose beauty Dorian believes to be in her acting. Dorian Gray’s narcissism becomes evident as he wishes that the portrait age so he could retain eternal beauty. The parallels between the dramatic storytelling and the author’s preface are striking. Wilde claims that beauty is not to be scrutinized for deeper meaning. It seems Wilde believes that beauty is superficial and meant to be enjoyed for its appearance only. To Wilde, the deeper meaning of beauty is potentially “corrupt” and without charm. Similarly, Dorian Gray’s charm is in his artifice, and not in his character. It is his character that ages hideously via the portrait, while his appearance remains in tact and beautiful. As though Wilde were saying that when we look for deeper meaning in people and things, we may not like what we find. Yet Dorian’s motivation in life is a debauched and shallow existence of self-indulgence. Wilde seems to say that we may appreciate the artifice of beauty but must be motivated by something deeper as long as we don’t assume that beauty has depth.

Christopher Lasch says that the narcissist is a “chaotic and impulse-ridden character. (They) lack the capacity to mourn… are sexually promiscuous... they avoid close involvements, which might release intense feelings of rage. [The patient has to attach himself] to someone, living an almost parasitic existence. At the same time, his fear of emotional dependence, together with his manipulative, exploitive approach to personal relations, makes these relations bland, superficial, and deeply unsatisfying. To be able to enjoy life in a process of involving a growing identification with other people's happiness and achievements is tragically beyond the capacity of narcissistic personalities.” Certainly Dorian Gray’s narcissism also led him to an unhappy existence and ultimately to his undoing. But did his narcissism and self-indulgence encourage madness and obsession? In his pursuit of beauty, Dorian loses his grasp on sanity as he indulges in a double life that will feed his vices and allow him the duplicity necessary for his inner narcissist to flourish. His duplicity also led to his madness. As he lived a double life, he was also forced to look at himself in the mirror so to speak. Each night he saw the changes in his portrait reflect his spirit. “He knew that he had tarnished himself, filled his mind with corruption and given horror to his fancy; that he had been an evil influence to others, and had experienced a terrible joy in being so; and that of the lives that had crossed his own, it had been the fairest and the most full of promise that he had brought to shame. But was it all irretrievable? Was there no hope for him? Ah! in what a monstrous moment of pride and passion he had prayed that the portrait should bear the burden of his days, and he keep the unsullied splendour of eternal youth! All his failure had been due to that” (Chapter 20). Wilde clearly admonishes the corruption of “pride and passion” which led to Dorian’s madness. It was his desire to indulge in beauty and the aesthetic that drove him to his horrifying demise at the hands of his own withered spirit. Wilde seems to say that the self-indulgence of the intoxicating power of all that is considered beautiful will lead to a withering of the soul. We must expect that the beautiful also sully our souls if we overindulge.

Dorian Gray’s madness is as much a reflection on the addictive qualities of beauty as it is a reflection of his eternal optimism. In other words, Dorian’s youthful beauty and foolishness were his downfall. It is a cruel reality that as our outward beauty diminishes, our spirit and strength of character becomes increasingly venerable. This contradiction between youth’s artifice and maturity’s profundity are constantly at odds with one another driving the narcissist to madness.

Oscar Wilde attempts to illustrate the ugliness of spirit in the horrifying portrait of the repulsive spirit of Dorian Gray. In the portrait we are witness to something we can never quite visualize, evil. Evil is within and therefore, not visible. But Wilde creates a picture of evil. The horror of this image is compounded when we contemplate that we are all capable of such ugliness. In its simplicity, the final image of the hideous spirit within Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde created an indelible and horrifying image of narcissism.

Transcendence and Horror: A Symbiotic Relationship

The genre of horror has become increasingly farcical in its unabashed attempts to frighten and thrill its audience. Over the years, as the visual medium has become increasingly sophisticated, the viewer’s expectations of what makes something genuinely horrifying has changed. Linda Badley says, “The visual and electronic media have been most directly responsible for the contemporary horror phenomenon.” In times prior to the advent of film, the reader of fiction was expected to use his/her imagination to visualize the depths of evil. As film reduced the need for our imaginations by providing the visual context of evil, writers were held to the same standards. The reader’s experience is equated to the experience of the visual medium. According to Badley, “modern horror fiction is as parasitic and omnivorous as horror film, incorporating movies and television, theatre and the visual arts, with equal gusto.” In other words, the more adept technology is at visualizing that which we previously could only imagine, the less need we have for our imagination. The result of this shift in technique has made the genre more farce than tragic transcendence.

There is a terror that can be simple and restrained. In its restraint, storytelling could be terrorizing simply by withholding information from the viewer. It is arguably more thrilling to be threatened by something we cannot imagine. The unknown is mysterious and, in its mystery, it becomes mythology. Therefore, the process by which tragedy becomes mythology and finally becomes horror has been clearly delineated over time. The tragic utilizes restraint to make its impact upon the reader. In its beauty, the reader is taken on an emotional journey that ends with unprecedented divine intervention that has dreadful consequences over the characters’ lives. An example would be Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, where tragedy and terror are created by poetic justice handed down by the gods. Whether divine intervention or human intervention, fantasy and gothic storytelling techniques create fear in its audience in mythological proportions. Mythology involves dramatic elements from another world to tap into the audience’s fears of the unknown. Greek mythology created the character of Medusa who could turn men into stone simply by looking at them with her head full of of snakes instead of hair. When storytellers expose the viewer to the things typically found terrifying – such as death, war, and human evil – indifference becomes inevitable. Horror is renewed by the act of exposure to death and the result is that the audience becomes anesthetized to the images of bloody corpses and violence because it is no longer unimaginable. Modern-day horror films like “Halloween” instill fear in the viewer by repeated and prolonged exposure to violent acts of murder. Over time, the only thing that becomes fearful is the editing technique that shocks viewers with the sudden appearance of the villain, and not the death scene, which becomes inconsequential to the initial shock of the unexpected (or even expected) appearance of the villain. Another difference between fantastical mythology and the horror genre is the element of beauty. There is no beauty in visualizing death, war, and evil. In fact, evil is predominantly visualized as ugly. Yet, in fantastical mythology, beauty surrounds the dramatic structure. Characters are beautiful; the death of a mythological being is charming; the tragic ending is poetic.

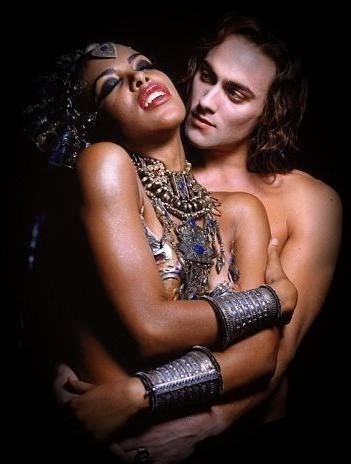

Anne Rice’s works of fiction – specifically her Vampire Chronicles – create a mythology of a world where vampires not only exist among the living, but also have a logical explanation for being. Rice’s prose is overwrought and self-indulgent. Yet, the predictable blood sucking and death is beside the point for Rice. The vampires question their very existence; they struggle with the death and suffering they inflict on the living; and they question the existence of a God that would give rise to such evil. To Rice, the vampire is a metaphor for the universal questions we all pose to ourselves and to our faith. They suffer more than their victims in their quest to find meaning in their very existence and in a world that would allow such evil to coexist with the beauty of life. “Rice’s transfiguration of Christian into erotic myth is similar to that of Madonna, another divided self, self-advertised lapse Catholic. As Madonna panted and sang of how sex made her feel “Like A Virgin” – reborn into radical innocence – Rice’s vampires tell us how being killed and killing are divine communion. Both transvalue the Church’s polarization of sexuality and virginity, death and life, the demonic and the angelic. Ultimately Rice’s iconography, like Madonna’s, expresses her ambivalence toward the female body as inscribed by Roman Catholicism – which made it potent with sacrilege and evil – and her ambivalence toward Church dogma” (Badley, p. 130).

To the extent that the characters are vampires, Rice’s work is considered horror. Yet, the themes she explores in her writing are existentialist and humanistic in their quest for beauty and religious transcendence. Louis is a 17th century Louisiana plantation owner when he is “made” by Lestat, the quintessential hero of Rice’s work. Louis is a tortured soul who questions the role of his kind in nature. Whereas Lestat revels in the fate he was handed. “In his craving for lost innocence, Louis becomes a self-flagellating masochist and pederast” (Badley, p. 108). To Louis, death becomes the enemy but to Lestat, death is his divine right. Lestat becomes the rock star, megalomaniac who relishes in his power to bring death to whomever he wishes and to bring eternal life to those he deems worthy. His God complex is the driving force of his existence. Among Rice’s other characters is Claudia the child vampire who remains for all eternity in the body of the 5-year-old girl she was when she was made into a vampire. She must live for eternity with the knowledge that she will never possess the beauty of a woman but instead will be confined to the body of an innocent. The female characters in Rice’s Vampire Chronicles are powerful creatures with masculine features such as virility, impulsiveness, and violence. However, male and female in Rice’s world are not the same as in our world. The vampire’s sexuality is not about power but about beauty. The characters seek companionship with other physically beautiful beings because they get pleasure from nature’s immeasurable power, and not for the desire of sexual copulation. According to Brown and Hoppenstand, “Rice’s grand and beautiful vampires appear perversely attractive. The tantalizing combination of evil and eroticism exerts a powerful grip over the modern imagination.” Rice’s characters seek heavenly absolution for a fate they were innocent in attaining. In The Vampire Armand – Book V of The Vampire Chronicles – a newly made vampire is educated in the ways of attaining a guiltless existence.

“The primary lesson was that we slay only "the evildoer." This had once been, in the foggiest centuries of ancient time, a solemn commission to blood drinkers, and indeed there had been a dim religion surrounding us in antique pagan days in which the vampires had been worshiped as bringers of justice to those who had done wrong. "We shall never again let such superstition surround us and the mystery of our powers. We are not infallible. We have no commission from God. We wander the Earth like the giant felines of the great jungles, and have no more claim upon those we kill than any creature that seeks to live.

"But it is an infallible principle that the slaying of the innocent will drive you mad. Believe me when I tell you that for your peace of mind you must feed on the evil, you must learn to love them in all their filth and degeneracy, and you must thrive on the visions of their evil that will inevitably fill your heart and soul during the kill. "Kill the innocent and you will sooner or later come to guilt, and with it you will come to impotence and finally despair. You may think you are too ruthless and too cold for such. You may feel superior to human beings and excuse your predatory excesses on the ground that you do but seek the necessary blood for your own life. But it won't work in the long run. "In the long run, you will come to know that you are more human than monster, all that is noble in you derives from your humanity, and your enhanced nature can only lead you to value humans all the more. You'll come to pity those you slay, even the most unredeemable, and you will come to love humans so desperately that there will be nights when hunger will seem far preferable to you than the blood repast."

Religion plays the ironic role of defying their very existence. They seek transcendence through companionship and erotic intimacy. The themes Rice explores are tragic and mythological in their reach, unlike the vampire stories of the modern day horror genre. In the beauty that the characters seek in their eternal existence, and the tragic restraint utilized in her storytelling techniques, Rice surpasses horror to achieve a modern mythology. It is the suffering and torture of the characters in the Vampire Chronicles that achieves the ultimate intimacy between them. The torture that surrounds their inevitable role in the death of humans is precisely what provides them with the satiating and transcendent sensation that is their bliss. And in so doing, the audience is horrified by the unimaginable world Anne Rice created.

Love Hurts: Marquis de Sade’s Quest for Emotional Intimacy

The search for emotional intimacy and a deeper connection between two people is among the most visceral and organic of all human experiences. We often consider a deep emotional connection to be closely related to acts of love. Pain and violence are at odds with the concepts of love and intimacy in our society. Yet mediated representations often explore themes of bondage, sadomasochism, and domination in sexuality. It would appear that there is a place for the darker side of sex in seeking transcendence and emotional connections. What is the relationship between physical pain and emotional intimacy and could it be a means of achieving an experience of transcendent love? The Marquis de Sade spent his lifetime in search of the answer. His work is reflective of his quest for an emotional intimacy, which he considered to go hand in hand with pain. De Sade has said “In order to know virtue, we must first acquaint ourselves with vice.” And among those vices was his interest in subversive sexual behavior. The more subversive the sexual behavior, the more profound the experience. In its need to be vulnerable to the power of another, the experience becomes more profound. The pleasure one experiences with another human being is among the deepest intimacy we can behold since pleasure is available to the vulnerable and emotionally available.

“It is always by way of pain one arrives at pleasure.” Or so believed the Marquis. His philosophy is not baseless. Certainly, those of us who experience transcendence and pleasure through sadomasochistic sex are at the mercy of another. The submissive of the two chooses to be vulnerable to the control of the dominating party. In doing so, the pleasure is in the attentions he/she receives. In a traditional and socially acceptable sexual experience, permission and respect are revered, yet the role of the aggressor and the submissive play out behind closed doors. We seek to either control, or be controlled, perhaps because it proves that we are desirable beyond reason to our partner. Without the feeling of an attraction beyond one’s control, the emotional connection becomes platonic and staid. Are love and pain mutually exclusive? Perhaps one must qualify the context of said pain. De Sade has said “I've already told you: the only way to a woman's heart is along the path of torment. I know none other as sure.” One interpretation, beyond the scandalous, is that a love that is naturally self-indulgent is also selfless. In other words, by indulging in one’s primal urges, the partner is able to experience a fully transcendent and fulfilling experience of desire and sexual intimacy.

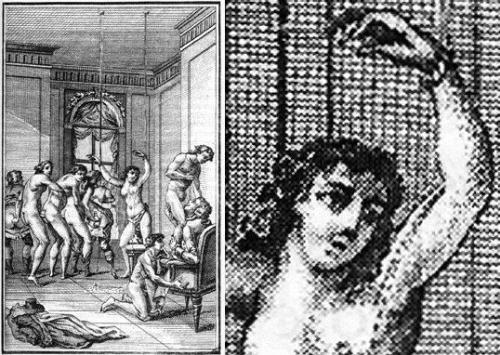

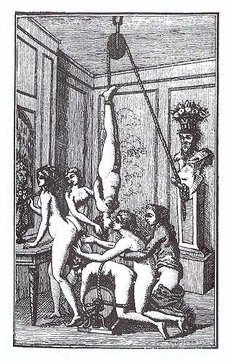

Among Sade’s work The 120 Days of Sodom is perhaps his most controversial. Feminist writer, Andrea Dworkin, has condemned it as "vile pornography." Dworkin considers Sade as a misogynist whose tales of rape and tortures are enacted on mostly female victims. Yet other scholars consider the work of Sade as satirical, among them Camille Paglia who claims that his work is a response to the Enlightenment’s concept of man's innate goodness. The 120 Days Of Sodom takes place over five months, during which four wealthy sexually depraved men enslave a number of victims as they listen to tales told to them by prostitutes that will ultimately inspire them in their own activities with their victims. It is interesting that he chooses to make the aggressors in his tale wealthy and aristocratic men. He describes them as "...lawless and without religion, whom crime amused, and whose only interest lay in his passions...and had nothing to obey but the imperious decrees of his perfidious lusts." Perhaps he was holding a mirror up to the aristocrats of the time and exposing their hypocrisy. It is especially effective since they are also figures of authority.

The revelations from the prostitutes are put in four sections. The simple passions are not simple in the commonly accepted understanding of the term. They include masturbating in the faces of seven-year-old girls, drinking urine and eating excrement. The complex passions involve vaginal rape of female children, incest, and sacrilegious activities. The criminal passions include tales of men who sodomize girls as young as three, men who prostitute their own daughters, and men who mutilate women by tearing off fingers or burning them off. The murderous passions include acts of skinning children alive, and burning entire families alive. Certainly the fiction of Marquis de Sade explores the darkest corners of a man’s mind. Yet as works of fiction they serve a greater purpose. They illuminate hypocrisy, the depths of depravity, and an atheistic view of the world around us. I believe his intention remained the same – to seek out emotional intimacy through pain and domination.

Sade’s work goes deep into the depths of human depravity and sexual perversion, yet it is also fascinating in its boldness. Just as contemporary mediated representations take on hegemonic views of sexuality and social mores, the Marquis de Sade boldly took on uncharted territories of the sexual experience, and its relations to pain and domination. Sade used his works of fiction to paint a picture of the potentially dark corners of our minds. The use of dramatic elements such as murder, torture, and incest, were tools to paint a satirical character portrait of the upper class of his time. Yet his own personal exploration of the subversive ultimately led him to an enlightened intimacy with people and with his own spirit.

The works of Madonna and Anne Rice similarly explore themes of a subversive sexuality that leads to a transcendent intimacy for some. I imagine the Marquis de Sade would be a fan of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles and its themes of transcendence through an acceptance of one’s inherent evil. Conversely, the self-possessed and dominating personality of Madonna might intimidate him since his pleasure was attained through torment and being the aggressor. Madonna would have wanted to dominate him. In today’s technologically rich media landscape, the Marquis de Sade’s philosophy of over-indulging in the pleasures of the flesh would be in direct contrast to modern interactions that are virtually acted out in cyberspace. Today, society acts out their dark fantasies of rape, pedophilia, and torture in the safety of the World Wide Web in virtual encounters without experiencing it first hand. Sade’s pleasure was in the emotional connection he attained through the activity. Modern virtual realities would have left him seeking more. Whereas, contemporary society reaches transcendental intimacy through the flirtation of the forbidden, Sade and his contemporaries had no choice but act their dark fantasies out in reality. Modern technology allows us the possibility of exploring the evil within virtually and not in actuality. Overall, mediated representations of the sexual might leave the Marquis de Sade cold in its artificiality and enhancements. Today we seek perfection beyond reason, but Sade was fascinated by the ugly side of men and women, both inside and out.

The Senses and The Artifice:

Organic Phenomena and Modern Technology

Mediated representations of sex and violence are a contradiction in terms. Sex and violence are organic in the sense that they are related to our senses and to our physical experience of the world around us. Yet, through the lens of media – whether strictly visual mediums such as print or interactive mediums such as television and film – the experience is removed and distant, not first-hand. The advantage for the modern culture of technology is the accessibility of different ways of thinking and living. We are capable of seeing and virtually experiencing other ways of life, other sensations of pain, love and of sex. However, those virtual experiences are poor substitutes for the first-hand experience. Diane Ackerman writes in A Natural History of the Senses: “What is most amazing is not how our senses span distance or cultures, but how they span time. Our senses connect us intimately to the past, connect us in ways that most of our cherished ideas never could.” As true as this statement is, technology does a more efficient job of bridging cultures, distances and time, but the virtual world is quite different from real-world experiences. Our imagination is a crucial element in making the virtual experience seem real. We use our imagination as a bridge between our senses and the fictional or mediated world. Our imagination makes it possible for us to relate to the mediated world, but it does not enhance the mediated experience. There is no substitute for the real thing.

Ackerman’s analysis of naturalistic and organic human experiences of love, sex, and pain is evocative in its descriptions. The five senses become real and tangible making a compelling case for the need to nurture the senses within each of us. Ackerman states that in order for our senses to be fully nurtured we must invite nature into our lives and exercise them regularly. There are examples of mediated representations of the organic. For example, the Marquis de Sade wrote many fictional works of sexual depravity and violent satire, but he based much of his work on personal experience. In doing so, he added an element of realism that makes the experience richer for the reader and much more mysterious. Similarly, Madonna’s many mediated representations are reflective of her personality and interests. In other words, the work becomes documentation for the artist’s personal reality allowing the audience to live vicariously through the experiences of another. The experience is therefore only once removed.

In contrast to Ackerman, Ollivier Dyens’ Metal and Flesh is an analysis of the inorganic and artificial modern experiences of the physical. Metal and Flesh discusses the future of the body in our machine culture. Dyens claims the physical body has become an intersecting place for biological and ideological principles. He says the body is not strictly biological but cultural in so much that it is completely dependent on technology for its survival. Dyens establishes two purposes for the body: (1) our bodies are repurposed to be cultural, ideological and scientific reflections of the world around us and (2) the networked body, in other words, our bodies becomes receivers of the world’s ideology. Dyens focuses on the "cultural biology" of the twentieth century, arguing that while the body "has always been subjected to extra-genetic influences," this is the century in which the relationship between the organic body and those influences has been most intense and most visible. Certainly, today more than ever, we are wired to one another in ways that have made it impossible to disconnect. We are much more adept at living through one another’s senses rather than through our own. Only in contemporary society could Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles be successful. Society has stopped questioning the potential realism in media and entertainment. We have gone from experiencing life through our own senses to experiencing life through technological representations of our senses. Dorian Gray’s rotted soul as depicted through his portrait horrified readers because the fear of one’s soul rotting from within was real and personal. The Vampire Lestat horrifies readers because of the possibilities of technology that has made it possible for us to visualize the horrors of a concept that is not based in reality. Technology has made the implausible a reality.

The sensorial experiences of a technological culture are limited to the visual through print, televised, filmed, and Internet mediums. Our gustatory, auditory, and tactical senses are not actively exercised in a technological culture. Sex and violence are particular phenomena in that they require active sensory participation. The scent of one’s partner in an intimate encounter, the taste of one’s partner’s kiss, the pain one feels in the sex act, the pain one might feel in the violent and savage interaction between one another, and the sound of another’s cry of pain or pleasure – a few of the sensorial experiences that are not available to us in mediated forms. The image in a print ad is not only artificial in its representation, but also distant in its intimacy. As we approach a new era in technological advancement, the Internet has proven to be a medium of unprecedented connectivity, similar to television and film, the audience is capable of virtually experiencing the unknown through realistic visuals and surround sound. However the Internet allows us to interact with one another like never before. Not only is the content based on real personal experience with little to no alteration, we can share our personal experiences for other’s to relive. The prospect of sharing our individual stories in a raw and unaltered format is new to a society accustomed to the digitally altered reality. It seems our technology is catching up to the needs of our natural senses.

Conclusion

Mediated representations of the organic have evolved over time. The consistency in the evolution is the sensorial. In other words, media and entertainment rely on humans connecting with one another through our senses. Our imaginations make it possible for us to virtually experience the media. We envision ourselves inside the structure of the drama and we identify with the situations. However, our senses make the experience (virtually) real. The importance of our senses is paramount to our enjoyment or identification of the mediated experience. Our imaginations are the bridge from our senses to the content.

The organic is irreplaceable, yet technology allows our bridges of imagination to span greater distances in time and space. Technological advancements enhance our imaginations by creating an alternate reality that was previously unheard of or unseen my human standards of reason and logic. Yet technology has also made it easier to create artifice where sensuality used to reside. Artifice and the quest for perfection has made our standards of beauty and our standards for pleasure unattainable therefore blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. Is the real and tangible more pleasurable than the potential of unachievable perfection?

Madonna made a career of exploring the limits of ideological representations of sexuality in media yet her points of reference were her own physical limitations of beauty. She sought pleasure in the ugliness of the human spirit and physicality. Images of her in Sex were intentionally raw and candid. A star of her stature would find it very difficult to resist the temptation of retouching away the imperfections and manipulating the creative process to make her look illogically perfect. Similarly, the themes explored would be safely within the status quo and not an examination of the taboo such as bestiality, sacrilege, or torture as Madonna did in Sex. Certainly the Marquis de Sade would have sought refuge in the dark corners of contemporary society while refuting the tendency to seek perfection instead of relishing in the unsightly.

The question of whether reality or artifice is ultimately more pleasurable remains to be answered. The answer may also be irrelevant. As we achieve heightened levels of pleasure through artifice, we may lose a level of intimacy that can only be achieved through organic experiences on an authentic level. Perhaps the ultimate goal is not pleasure but intimacy. In fact it is intimacy and transcendence through intimacy that the Marquis de Sade sought. It is also intimacy that Anne Rice ultimately sought through her characters of the eternally damned. They were eternally damned, not because they were dead among the living, but because they could not experience love and closeness with humans without causing their death.

If it is intimacy that we seek, technology is not the answer. Technology and the Internet have brought us all closer than we have ever been; however, it is at the cost of intimacy.

Works Cited

Ackerman, Diane. Natural History of the Senses. New York: Random House, 1990.

Badley, Linda. Writing Horror and the Body: the fiction of Stephen King, Clive Barker, and Anne Rice. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Browne, Ray B. and Gary Hoppenstand. The Gothic World of Anne Rice. Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1996.

Dyens, Ollivier. Metal and Flesh: The Evolution of Man: Technology Takes Over. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001.

Fouz-Hernández, Santiago and Freya Jarman-Ivens. Madonna's Drowned Worlds: New Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003. Vermont: Ashgate, 2004.

Gillete, Paul J. (Translated by). The Complete Marquis De Sade. California: Holloway House Publishing Co.

Guilbert, Georges-Claude. Madonna as Postmodern Myth: How One Star's Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood, and the American Dream. North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002.

Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: Norton & Company, 1979.

Madonna. Sex. New York: Warner Books, Inc. 1992.

Paglia, Camille. Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Paglia, Camille. “Madonna – Finally, A Real Feminist.” The New York Times 14 Dec. 1990.

Rice, Anne. Interview with the Vampire. New York: Random House, 1976.

Rice, Anne. The Vampire Lestat. New York: Random House, 1985.

Rice, Anne. The Queen of the Damned. New York: Random House, 1997.

Smith, Jennifer. Anne Rice: A Critical Companion. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Random House, 1992.