Robert Max Jackson

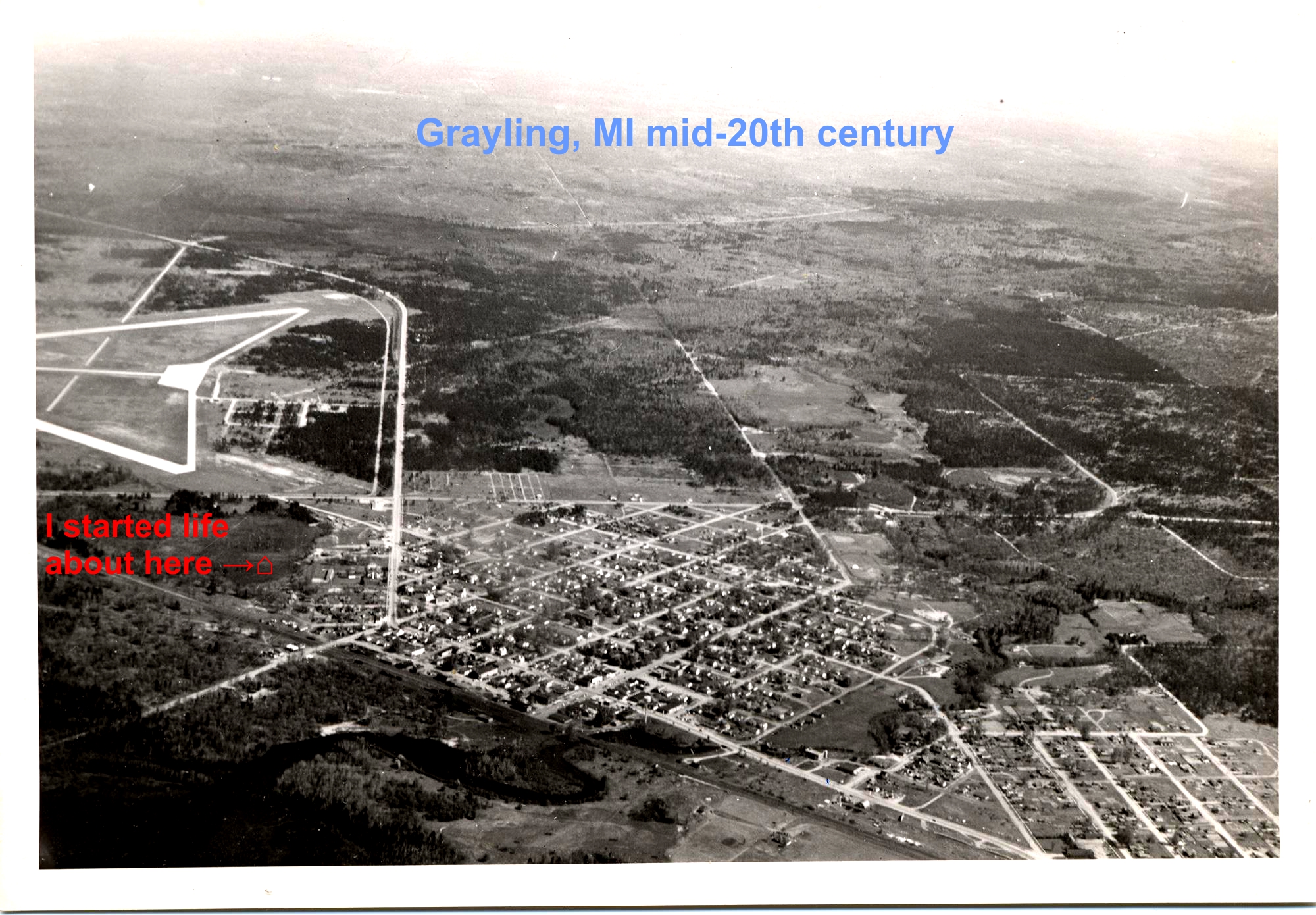

Like everyone else, my biography begins in a social context defined by my family and surroundings. I was born and raised in a small Michigan town (think 2,000 people) about 200 miles north of Detroit, called Grayling (after an extinct fish, unintendedly symbolic of the town's history). My parents were poor and uneducated (neither had gone through high school), my mother an immigrant who fled Nazi Germany, my father the only child of rural, wandering parents. My parents were marginal people who did not fit with any group in our small town, and I became a similarly marginal kid within our community school. From my days growing up in this town I came to value women as friends, to expect that women worked, to not believe women were nurturing, to consider marriage suspect and families untrustworthy, and to anticipate that people from affluent backgrounds were always ready to screw you over.

Parents.

My mother was born in Minden, Germany where she lived with her Polish Jewish family until the purge of Polish Jews associated with Kristallnacht. Her immediate family were all rounded up and sent to the Warsaw Ghetto - they all died either there or at one of the death camps such as Treblinka (the exact fate of most of the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto is unknown). My mother evaded capture by the authorities for about six months. As was common for people with such experiences, she was never able to describe how all this happened. She never completed secondary school (and apparently did poorly in school), but she was wily and adaptive. She was finally picked up and slated for deportation, but through intervention, luck, and pluck managed to get to Britain through a labor shortage exception as a domestic worker just before the border was closed. After spending some time at a farm and serving with the Women's Land Army, she spent The Blitz and the remainder of the war in London, where she met my father who served in the Army Air Force. She became his "war bride." My mother was a narcissistic manipulator, who always was certain that life had let her down. Of course, it had, which translated into a lever to make everyone guilty.

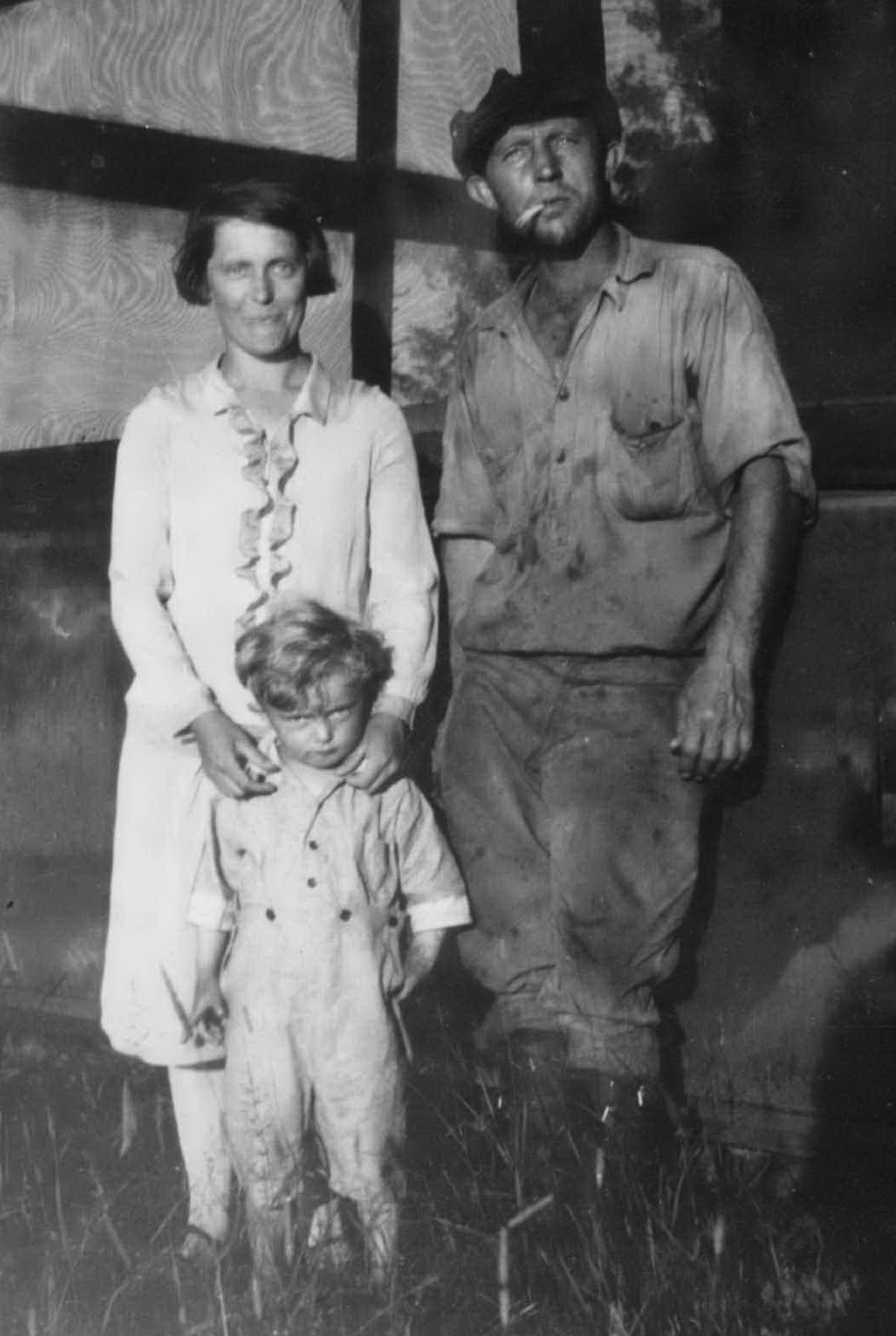

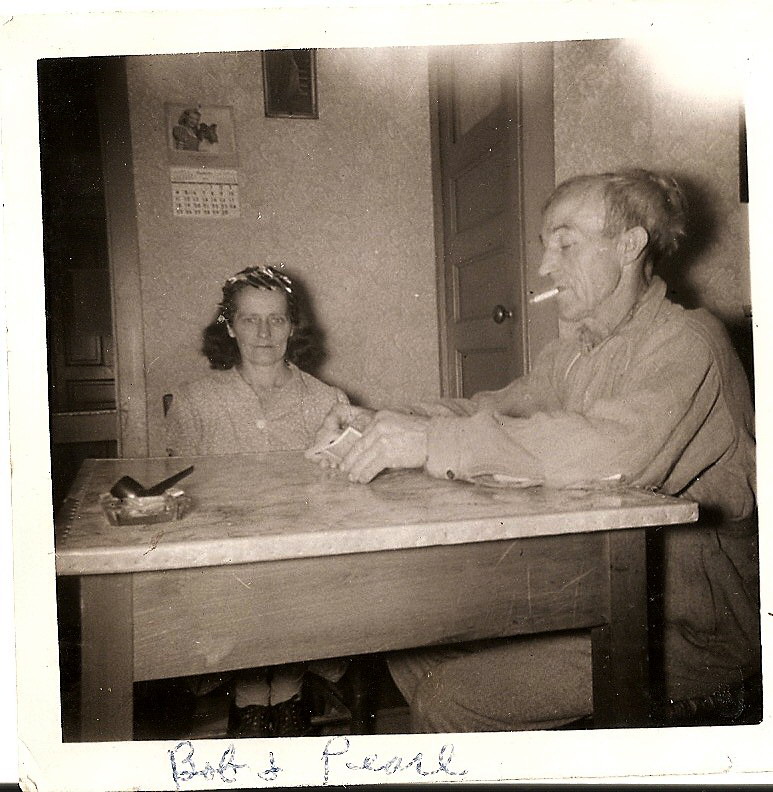

My father was born in rural Michigan, the only child of a farmer's daughter and her wanderlust boyfriend, later husband. They lived working-class lives, with my grandfather embodying much of the rugged male ideal. He had a lot of outdoor positions, from guarding the Mexican border as a soldier, to guiding hunters in Michigan, to spending WWII trapping beaver in the Grand Canyon for the government. My grandmother was one of nine children in a farming family who had only one son whom she seemingly found unworthy compared to his father. My father never seemed to do anything very well, which I suspect reflected the judgments that his parents had of him. He was a nicer person than my mother, but too sad and angry for people to notice.

|

My mother's mother (with my mother as child) |

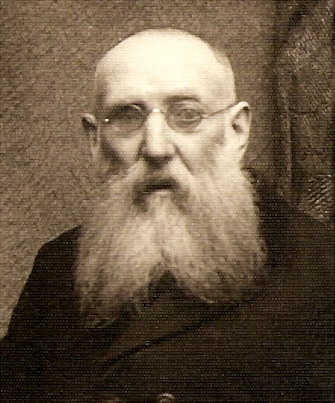

My mother's father, Hersh Wolf Ingberg. |

|

My father's parents, later in life (Robert Lee Jackson, Pearl Ferguson Jackson) |

||||||

|

My mom as a London hotel worker in WWII after escaping Nazi Germany. |

My parents, engaged in England at end of WWII. |

My parents, my brother, and me (curly hair). |

|||||||

We were poor, and this class identity is more salient in my biographical experiences than gender. My father only had a couple years of formal schooling, was largely lacking in social skills, and was frightened of authority. None of which is to suggest that he was dumb or lacking in ambition. For about the last 20 years of his life (he died at 60), he worked as the caretaker for the local golf course. During the non-winter months, he would go work at about 5 in the morning and work until about 5 in the evening with breaks for breakfast and lunch, then he would go back for a couple hours after dinner - except on Sundays when he worked just a half day. Over these years he acquired a level of knowledge about caring for a golf course approaching that of college educated professionals, but I don't anyone really noticed, including his family. His life embodied the lessons that one should work unceasingly but also that one will not get rewarded for effort. I think I was most affected by the first lesson and my brother by the second. My mother was a fish far out of water, an uneducated immigrant in town with few immigrants, a Jew in a town with no Jews, a cosmopolitan European who had nothing in common with the local poor people who she disdained. My mother too was much more than she seemed. Avoiding the Nazis, finding a way to escape Germany, and teaching herself to read and write English from newspapers without any help, I am always dumbfounded when I think of these feats which seem ill fit to the unhappy mother I knew. I suspect that my parents began happily, but their marriage was a long sad tale of anger and disappointment, two people with extremely different backgrounds struggling with overwhelming economic insecurity, with neither having friends to whom they could turn.

|

|

|

|

Our house and us. The house was built by my father and grandfather. It was covered in tar paper, a poor people's siding, particularly popular in the South. The pump in the bottom photo was our only source of water. We had no plumbing, no sewage. Our "outhouse" was a ways off to the left from where the person taking the photo was standing. |

|

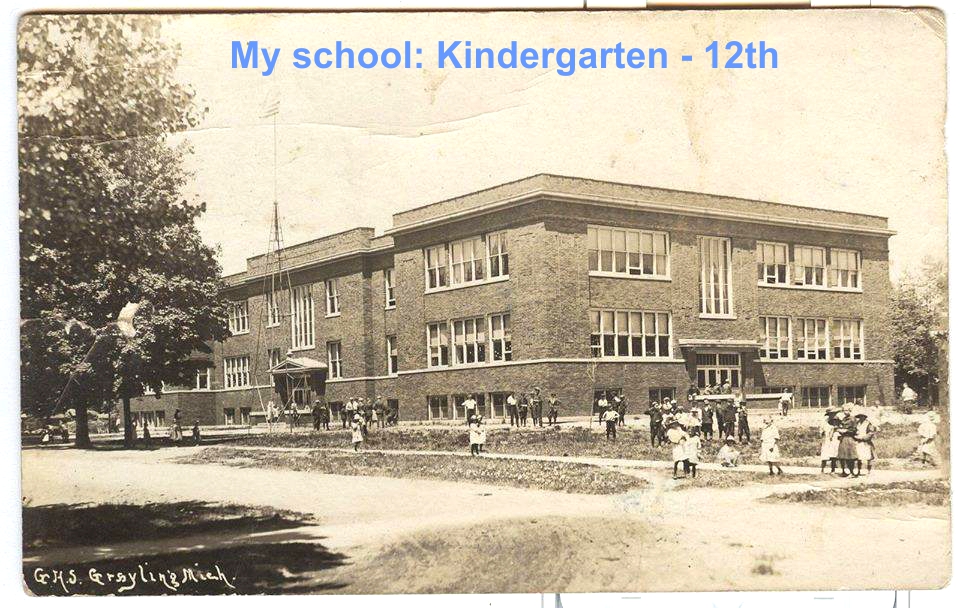

I was the kid from the poor family with the immigrant mother who startled everyone by being a good student. I recall being chased and called names by other kids at elementary school, because I was an outsider and I was violating the clear rules that poor kids should do poorly at school. By high school this changed somewhat. I was then not just a good student but seen as the smartest kid in school, which might not have meant much on its own, but my willingness to challenge anyone (including teachers, some of whom seemed to resent that I knew more than they did) made people nervous. The result seems to have been that the middle-class kids, who were all the better students, kind of accepted me during school. They simply left me out after school. Also, I think that some of them began to sense, even if they did not really understand, how much repressed anger I carried around. People were wary of me, something I did not really grasp until high school had ended. Somewhere in the midst of this, I developed most of my school friendships with girls. I think that the link was that I did not really grasp the expectation that girls should not aspire and succeed the same as boys. Also, I had become so alienated from parents by high school, that school for me was how I could escape. I did not like my town, I did not like my family, I despised middle-class mores (which I thought were all a deception, probably reflecting my experiences with middle-class kids), and I saw education as my means of escape. I empathized with the girls who seemed to feel the same.

|

All of Grayling from the air. Our house was on the edge of town, down a dirt street the town didn't notice. |

I went to the same building for all 13 years of my schooling (here shown in 1921 when new). |

|

Main Street, 2 blocks long with the only stop light in town in the middle. |

Shoppenagon's Inn in my home town, where my mother worked as a maid just as she had in London. |

The influence of my social background on the development of my gender identity

Women worked in the world I knew as a child (long before those in this class were born, of course). My mother quit working when my younger sisters were born, but had been working for about 20 years. Although fewer in number, women worked alongside men in the only factory in my town (which produced bows and arrows), and where I worked for a total of about 8 months. The women in my grandmother's large family all worked, on farms, teaching, as domestic help. And, of course, my school teachers were largely women. So, I grew up thinking women worked - those who did not were odd.

Because my father was uneducated, having spent only a couple years in school around the level of the 6th grade, and had no trade skills, he had few job alternatives in a small town. He was paid poorly and spent years unemployed. He finally got a lasting (but low paying) job caring for the local golf course, which required him to work about 13 hours a day, 6 ½ days a week during the non-winter months. He constantly fought a sense of being a failure, a condition exacerbated by my mother daily proclaiming that he was a failure to him and to us children. Exactly how this affected me is difficult to say, but I certainly acquired a belief that one needs to work all the time to forestall an ever threatening failure and that men who signed up to provide for a family were placing themselves in jeopardy.

My parents were not, as far as I could ever see, good at parenting. I have always thought of them as terrible. I suspect my father cared deeply about his children, but could not figure out how to show it and felt inadequate. As best I can tell, my mother had no capacity to feel deep affection for anyone, including her children (although my siblings seem still to lie to themselves about this). My grandmother who lived across the street from me until I was about 10 seemed taken by my brother who resembled her husband, my grandfather (who died when I was 5), in both looks and demeanor, but had little interest in me. Whatever effects these experiences had, they did not lead me to expect women to be nurturing (and I scoffed at people who suggested they were). And, I felt that marriage was a suspect institution.

In middle school and high school (continuing in the same building with the same kids) I became known as the super smart kid, and I played sports in a middling fashion. I was friends with girls who got good grades while in school and with boys who were somehow marginal outside of school. I loved art above all else but dominated everyone in math, science, and anything requiring analytical thinking. I studied many hours every night and always saw my achievements as representing effort, never inherent talent. There was no one with whom I shared my secrets or my passions and I was comfortable being alone. Mostly, I suspect what came from this muddled mess was a lack of ease with what others experienced as normal customs, and a disdain for the ideas with which they explained and honored those customs.

I went to Michigan on a full scholarship, and found myself in a world of people with whom I shared almost nothing. I found that I was a young, heterosexual guy who liked women as friends more than men, who had largely not learned gender stereotypes about roles and skills (which largely seemed perplexing and bizarre to me), and who did not understand why people thought anyone's sexual orientation, including their own, was of any interest (beyond knowing who was or was not potentially sexually available).

Perhaps more than anything else, my life embraced a belief in meritocratic ideals. Of course, this was at least as much a reflection of self-serving interests when I was young. I loved reading and thinking and figuring things out. They were my solace and my protection in a world of emotional, interpersonal, and economic chaos. With time, however, they became my armor and my weapons, the means to ward off those who relied on their social status. Of course, like all weapons, their effectiveness depended on the terrain and enemy. The best terrain was in education, where other status characteristics still counted, but where they were unsure shields against a strong analytical attack. Because academic achievement and meritocratic ideas were my standards to fend off the implications of growing up poor, it was hard not to see common cause with women's parallel efforts. And, indeed, the efforts of all kinds of people who were vulnerable just for being different. I had a long history experiencing the perception of being different.

Of course, this is just the beginning. But the rest must wait until another time.

|

Me, the curly haired kid. |

Me, the curly haired college student. |