|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What Do I Get? Punk Rock, Authenticity and Cultural Capital.

What Do I Get? Punk Rock, Authenticity and Cultural Capital.

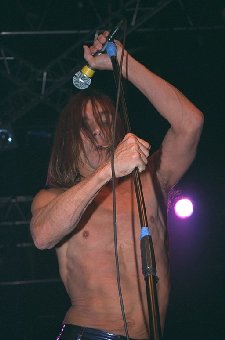

By Brian Cogan Advertising and Punk Rock The prevalence of punk is no doubt due in part to a simple change in demographics. A new generation of advertisers, weaned not on the counter-culture of the 1960's but on the punk rock and new wave of the late 70's and early 80's, now dominate the industry. The new generation, many of who enjoyed punk rock, but like most music fans, ignored or resisted the alternative ideology of punk, may have simply wanted to use music they were more familiar with and enjoyed more than the constant recycling of 60's songs that dominated advertising throughout the '80's. In a sense, this was just a natural musical evolution. The new generation, now dominating the creative departments of most major advertising agencies, wants to use the music of their youth, rather than the music of their supervisors' youth. This is also a result of most musical communities not connected with the ideology of the music, just as most Public Enemy fans, a good percentage of whom were white middle class youths, could dismiss the occasional anti-semetic outburst of the group's "Minister of Information," Professor Griff, so too could punk fans enjoy the music of The Clash, perhaps, without realizing their strong leftist credentials. It is no coincidence that their most overtly political album, Sandanista, was also their weakest both in sales and critical acclaim. The people working in advertising agencies who introduced punk to the mainstream via ads for cars using bands such as The Buzzcocks (Toyota), The Smiths (Nissan) and The Minutemen (Volvo), were most likely not part of any conspiracy to plunder the underground for mainstream fodder, but instead were simply using the music they had grown up with to sell the commodities their job required. And if the advertisers had found themselves abandoning their punk roots to sell products, their target audience suddenly found themselves in need of products to buy. As Devin Gordon pointed out in a recent article in Spin Magazine, "those Smiths fans, arbiters of cool in their youth, are now in their late 20's and early thirties, right about the age when people make their first 'serious' car purchase." Except for a few diehard fans, most punks find that they must reintegrate themselves into the real world and in doing so end up purchasing many of the same commodities they once scoffed. Nor are the bands themselves blameless either. Clearly no one held a gun to the head of Iggy Pop (who advertised for Nike) or forced Black Flag to sell their classic song "Rise Above" to a manufacturer of video games. What happened was simply that a generation came of age and infiltrated the industries they once derided. Advertisers, being fairly astute, tried to create a connection between the (presumed) counter-cultural activities of their audiences' youth in order to identify consumption with rebellion. And, as with Nike's use of "Revolution" a decade earlier, some fussed and cried sellout, but many may have been simply amused to see the music of their youth used in this fashion. As Simon Frith notes, rock music has always "articulated the reconciliation of rebelliousness and capital." Likewise, Douglas Kellner has also pointed out that advertising itself is part of the active process. As Kellner wrote, "all ads are social texts that respond to key developments during the period in which they appear." The fusion of punk rocks' subversiveness to the imperatives of a market economy can then be regarded as almost inevitable. Naturally the punk 'zines, bulletin board and listservs were aghast, but for most of America the protest was marginal. ImplicationsWhat are we to make of the use of punk rock in mainstream advertisements? On the one hand, this could be seen as the usual commodification of a subculture by the mainstream, exactly what Hebdige described over twenty years ago. But this perspective ignores the American version of the punk rock narrative, the narrative where punk was not a community based on class, but rather on taste. Perhaps this is actually an example of what Pierre Bourdieu calls cultural capital, although Bourdieu identified it as exclusively a function of the dominant classes reserving specific art forms for their own privileged uses. Nonetheless, it seems logical that specific subcultures can, over time, develop cultural capital of their own. The cultural capital of punk rock is the closely guarded canon of music, which provides entrance into the mysteries of punk to those immersed in the "correct" music. Punk allowed itself to become a closed community of elitists, and in a sense the punk community became as restrictive as the mainstream culture they supposedly opposed. Punk zealously resisted the commodification that mainstream exposure offered, but at the same time it kept the best parts of the movement, the propulsive and almost organic music, at the core of punk, for itself. In doing so and resisting mainstream methods of distribution, punk rock closed itself off from the rest of the world, espousing a supposed philosophy of liberation, but for only a few thousand adherents, bound together by a rejection of all things mainstream, and a rejection of those who sought to join without benefit of the proper forms of initiation. By the turn of the century, a movement that was supposed to have been all-inclusive became elitist. This is why I believe there are positive aspects to the new rash of advertisements using punk, alternative and even club music to sell products. While we may rightly decry the sheer ubiquity of advertisements and a culture founded on advertising as a way of life, we cannot ignore the pervasive influence and vast reach of advertising in general. The exposure of punk to a wide audience in this light can be seen as a way of spreading punk's cultural capital into the mainstream, which has long resisted the punk movement, and surely a commercial in limited release reaches many millions more than all of the college radio and underground distribution networks that punk relies upon combined. As Gina Arnold noted, while punk has become the perfect target market, the potential is still there for co-option of the very products being advertised. Also, as Keith Negus has noted, there is not necessarily a connection between who controls a product and how it is consumed. What I am saying will no doubt seem like heresy both to those who eschew advertising as an environment and those within the thick of current punk culture. Those who do wish punk to be distributed to a wider audience often point to new technologies, such as Mp3 and new modes of distribution like Kazaa, as a logical and more promising extension of punks' DIY aesthetic. This hope is somewhat nebulous at the present. Napster, for example, was the target of much legislative lobbying by major record labels and eventually shut down. As authors such as David Marshall have pointed out, the Internet may be evolving into a network model, following a pattern that he identifies as "access, excess and exclusion," where large corporations crowd independent voices into the margins. So, while those avenues are closed off or marginalized, it may be that punk rock can reach a wider audience by using the mainstream as its carrier. At its best, this form of cultural capital could act as a virus or meme, infecting the mainstream and allowing greater access to the music, and perhaps even some of the fertile anarchistic genius of punk, than both the major record labels or even the insular punk community have previously allowed. ConclusionOf course, whether this will be ultimately beneficial is by no means certain and there are many disadvantages, none the least is the fact that punk communities are notoriously picky about whom they accept as members in the first place. Also, the music used in commercials is not identified by artist and most people will certainly not know to whom they are listening, but then again this is the case with most radio stations who do not identify artists immediately after playing a song. There is also the danger that many people will either miss or turn off the commercials, whether they know the music or not, because it is just another annoying interruption of Friends or Buffy. All of these are very real problems and require greater analysis than an article of this length is able to discuss. But if punk is to be legitimized, it needs to stop hiding behind a mask of purity and start to make overtures into the mainstream, to let some of its closely guarded cultural capital out into the real world. With mainstream radio and MTV still closed (and becoming more restrictive on a daily basis), and the future of the Internet in turmoil, it may be that what most people regard as commodification is a blessing in disguise. At the very least, it may allow some people to actually experience punk rock in a non-judgmental way, without the attendant baggage of punk's codes and rituals. Also, any exposure to "underground" music, with all the accompanying elements of style and taste, helps to refresh the mainstream from becoming stale. In short, the introduction of punks' cultural capital, and of the virus of punk rock into the mainstream via commercials, may do more to affect culture in general than twenty-five years of self-imposed marginalization. Although some suggest that one of the main principals of punk is its uncompromising stance towards co-option by the mainstream, this principal can also lead to calcification when taken to its logical extreme. If punk rock is to remain a vital force both as a (somewhat amphoras) political movement and as a musical community, it must learn to engage the mainstream, rather than pretend that it simply does not exist. If commercials are the first step in this process, then ultimately the "commodification" of punk may open more doors than it closes. ReferencesArnold, Gina. Kiss the Girls: Punk in the Present Tense, NY: St. Martins Press, 1997. Cartledge, Frank. "Distress to Impress?: Local Punk Fashion and Commodity Exchange" in Punk Rock: So What, Roger Sabin, Ed. London: Routledge, 1999. Ewen, Stewart. All Consuming Images: The Politics of Style in Contemporary Culture USA: Basic Books, 1988. Fenster, Maximum Rock and Roll, pg. 146. Frith, Simon. Music for Pleasure: Essays in the Sociology of Pop, NY: Routledge, 1988. Gordon, Devin. "Car Tunes for New Grownups: Advertisers Tap the Music of a Previously Jilted Generation." Spin 60,Vol. 16, No.6, June 2000, pg. 60. Hebdige, Dick. Subculture the Meaning of Style, England: Routledge, 1979. Heylin, Clinton. From the Velvets to the Voidoids: A Pre-Punk History for a Post-Punk World, USA: Penguin Books, 1993. Kellner, Douglas. "Advertising and Consumer Culture" in Questioning the Media: A Critical Introduction, Roger Dowling and Ali Mohammadi, eds. California: Sage Publications, 1995. Marshall, David. "New Media Heierarchies: The Web and the Cultural Production Thesis" in Thinking New Media Sydney: Pluto Press, 1999. McNeill, Legs and McCain, Gillian. Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, New York: Grove Press, 1996. Negus, Keith. "Popular Music: Inbetween Celebration and Despair" in Questioning the Media, pg. 388. << Page 1 >> Page 2 >> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

:: I. M. Pei's La Pyramide du Louvre: A Diamond in

the Rough or Merely Junkspace? By Rebecca L. Moyer :: The Culture of the Fence: Artifacts and Meanings By Christina Kotchemidova :: On the Significance of Death in Culture & Communication Research By Charlton McIlwain, Ph.D. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

:: Swept Away By An Unusual Destiny In The Blue Sea Of August: Lina Wertmüller, 1974 - Guy Ritchie's Swept Away 2001 By Laura Meucci :: What Do I Get? Punk Rock, Authenticity, and Cultural Capital By Brian Cogan The Osbournes': Genre, Reality TV, and the Domestication of Rock 'n Roll By Rick Pieto and Kelly Otter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ::

About Contributors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| About :: Archive :: Staff :: Submit :: Contact | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||